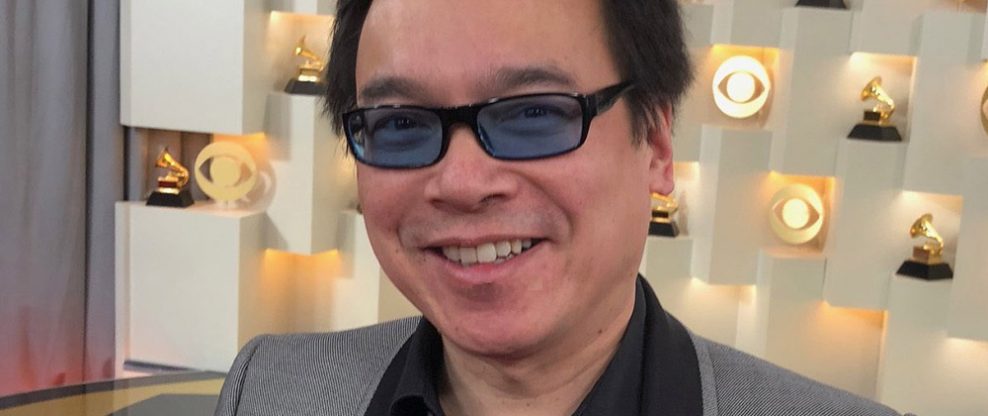

This week In the Hot Seat with Larry LeBlanc: David Lai, co-president, Park Avenue Artists.

Co-presidents/co-founders David Lai and Ross Michaels operate Park Avenue Artists, the Manhattan-based boutique management and production firm.

Its activities include overseeing specific management needs of one of classical music’s leading lights Joshua Bell, as well as the management of a high-caliber roster including singers Ryan Silverman, and Ashley Brown; actor/singer/dancer/director Jordan Donica; singer/songwriters Yebba, Mia Gladstone, and Marco Foster; the classical garage band Time For Three; Houston-based wind quintet WindSync; Australian saxophonist Amy Dickson; and Mexican pianist Daniela Liebman.

Lai himself traverses the entire spectrum of the entertainment universe.

Within Broadway’s theatrical community he is renowned as a highly-sought after conductor, music director, music coordinator, orchestra contractor, and keyboardist.

He is the long-running–almost 24 years–music director/conductor of the Broadway company of “The Phantom of the Opera”.

He has also served as the orchestra contractor/music coordinator for Lincoln Centre Theatricals since 2008, including for the production of “My Fair Lady” which has just opened.

Among his credits, working in different working roles, are Broadway productions of “Fiddler on the Roof,” “The King and I,” “Evita,” “Mary Poppins,” “Wonderland,” “South Pacific,” “Miss Saigon,” “The Woman in White,” “Riverdance,” “Jesus Christ Superstar,” “Les Misérables,” and “Aspects of Love.”

Previously, Lai served as senior VP at IMG Artists (2012-2015); as senior VP A&R Operations, Sony Music Entertainment (2004-2014); and as senior VP at Park Avenue Talent (2007-2011). He began his music career in New York with a 15-year stint (1989-2004) at Sony Music Entertainment as its VP of Business Affairs.

Along the way, Lai has worked on teams overseeing management of Renée Fleming, 2CELLOS, Kate Davis, the Five Browns, and Eldar Djangirov.

He production credits include recordings by Djangirov, Joshua Bell, Nathan Gunn, Kristin Chenoweth, Audra McDonald, Howard McGillin, Laura Benanti, and Ashley Brown.

Among the cast albums he has produced are Broadway productions of “West Side Story” which earned a Grammy Award, “South Pacific,” “Grease,” “Evita,” “The Wedding Singer,” “Sunset Boulevard,” “Bonnie & Clyde,” “Elf, “Wonderland”; the Spanish-language cast albums of “The Phantom of the Opera,” “Jesus Christ Superstar,” and an all-star cast album of “Allegro.”

Lai received BAs in Engineering, Economics, and Music from Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, and an MBA in Finance and Marketing from Columbia University in New York City.

You worked with Kiss frontman Paul Stanley in 1999 when he took over the lead of the Toronto production of “The Phantom of the Opera.”

Well, it was one day. They didn’t tell me who it was going to be. They said that they wanted me to work with somebody who may be joining the “Phantom” company in Toronto. “We want to do work sessions to see if he can do it.” I show up at the Ford Theatre (New York), and it’s Paul Stanley. I think, “Holy mackerel. The ‘Love Gun’ guy is right here.” So I’m thinking that this is a stunt. This is going to be terrible. He’s not the obvious choice as a vocalist, but he made it work because he cared so much, and he worked so hard. That he wanted it to be successful. He wanted to do it right. There’s no doubt that this guy has an incredible presence. Even walking into the room wearing 5-inch heels, he has so much presence.

[Paul Stanley has described ‘Phantom’ rehearsals, and working with a vocal coach as “the hardest work I’ve ever done. Six hours a day. I went home every night slumped in the back of a taxi, exhausted emotionally and — because of the demands of singing a different way and the physicality of the role, and the staging — physically.”]

The first obstacle Paul would face was learning how to use his voice in a new setting, figuring out the breath control needed for the show’s musical numbers.

When I am teaching a “Phantom,” or teaching any actor for a show, I go through all of the elements: Telling them what the context is, and giving them an idea of what to expect musically. About the story that, “This is what you are trying to further here.” I don’t get too much into the direction because that’s a different department, but I do find it helpful to give context to the actors, rather than saying “get louder or get softer here; use your inner voice, use your falsetto.” If you tell them what’s happening, if they are a good actor, they will know what voice to use. Chances are they might come up with something that I would not have thought of that is even better.

I take it that with a musical the book belongs to the director and a dialogue coach; the dance segments to the choreographer; and that when it comes to the music you share that landscape with the director who has the final say.

As a musical director, I focus much more on the music side. I don’t get that much into the storytelling, but I use that to help an actor find music that will work because it’s much easier to get the actor to come up with the right thing when they know the story that they are telling.

Have directors always given you wide latitude or has that come as you built your career and with experience?

It comes with competence and experience, The more I know, the more I have worked on things. The more I’m comfortable, the more latitude that I have been given. But a lot depends on the director. Some directors are very controlling. Other directors encourage collaborations and the collaborative process.

After years of struggling, creative people can reach the point in their careers where they walk into a room and everybody is of the same stature with similar expertise. Have you gone through that transition?

Yes, because they are such tight communities, both the Broadway world as well as the classical world, you hear what everybody is doing. There’s not as much noise, as say, the pop world. There will be 10 or 15 new (Broadway-bound) shows so we are all aware of them, and who are working on them. So it’s a tight community and because we all have such passion for the music in the shows that we do, yes, I’m very aware of that. It’s kind of a cool thing, actually.

That there is a Broadway bond was most evident following Tony winner Ruthie Ann Miles and her daughter Abigail Blumenstein being struck by a car earlier this month, and her daughter dying. Ruthie Ann’s unborn baby was unharmed. Broadway has since shared an outpouring of support for Ruthie Ann on social media. Obviously, this is a tight-knit community from the actors to the musicians to those working behind the scenes.

It is a very, very tight-knit community, and we all consider ourselves family because it’s a tough thing to get the opportunity to work on Broadway. So if you are here you appreciate what everybody else has gone through just to get here, and you have a lot in common. So with a tragedy like this, you can see the love and support. Not that this is a complete indication, but a company manager at one of the shows set up a GoFundMe to raise some money to help out the family, and set the goal of $5,000. About 12 to 20 hours into it, they were close to $300,000. Obviously, no amount of money will make up for the loss of her daughter, but I hope that the expression of love and care and the prayers from all of the community, I hope that helps the family.

Ruthie Ann performed the role of Lady Thiang in the Lincoln Center production of “The King and I” on Broadway, for which she won the 2015 Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Musical.

Ruthie Ann is one of those incredibly special people. We met through “The King and I.” I remember opening night—I was the contractor and, so while I don’t deal much with the actors, I got a hand-written, beautifully-written note from Ruthie Ann saying, “Thank you so much for giving us this wonderful orchestra. It means so much to have such care for our production.” That was extraordinary. Then when “The King and I” was nominated for a Grammy (for Best Musical Theater Album) we sat together in the 10th row for the awards, but that was the year of “Hamilton.” So it was one of the very few times that a Broadway show gets to be on television, and it was with “Hamilton.” So we got to sit there and chat and enjoy life and be on national television for 0.2 seconds. It was a pretty exciting time.

There are, perhaps, three categories of stage musicals: The jukebox musical, like “Mama Mia,” “Jersey Boys,” and “Motown,” in which popular songs dominate and a storyline is secondary; the concept musical, originating in the ‘60s and ‘70s with the likes of “Man of La Mancha, “Cabaret,” “Hair,” and “A Chorus Line” in which music, lyrics, dance, staging, and dialogue are woven through each other rather than flowing out of the story; and finally, there’s the mega musical that includes “Cats,” “Les Misérables,” and “Miss Saigon” utilizing spectacle and technology alongside the plot, characters, book, and score. So there are broad differences today in what is considered a stage musical?

Absolutely. You have encapsulated really well the different kinds of musicals that there are. It changes, obviously, from generation to generation.

Today there’s so much crossover between Broadway and Hollywood. Decades ago Broadway was adjacent to Tin Pan Alley, and successful stage productions went on to be films. Following such jukebox musicals as “Mama Mia” and “Jersey Boys” there’s been more back-and-forth with contemporary music, and with Hollywood.

Coming to Broadway will be productions of “Pretty Woman: The Musical,” “Tootsie,” “Working Girl” with Cyndi Lauper doing the music, “Mean Girls,” and “The Devil Wears Prada” with Elton John involved.

Going the other way from Broadway are films being planned for “Come From Away.” “American Idiot,” “Beautiful, The Carole King Musical,” “Cats,” “”Wicked,” “Guys and Dolls,” and “West Side Story.”

Movies becoming musicals, that certainly seems to be the trend right now. It will be interesting to see how “Mean Girls” does, and how “Pretty Woman” does. There are still great original pieces like “Hadestown” which I was fortunate to work on last year (for an Off-Broadway run). That’s an original work. Anaïs Mitchell, I only knew a little bit about over time, but I am now a huge fan. Wrote this incredible score, and the story that is being told is special. It was done at the New York Theatre Workshop. The hope is that it will be on Broadway.

Many Broadway productions have started off in regional markets like “Escape to Margaritaville,” and “Dirty Dancing,” with “Flashdance” again vying to make the jump five years after being announced.

More and more now I think that it is very wise for producers to be testing productions out elsewhere. In New York City, you can hire the greatest actors to do workshops for very little money, and see how it works. The thing that I have learned over the years is that no matter how good the production values are that if you don’t have a story that moves people, that has a story to tell, no matter how great the music is or how great the dancing is, it is likely not going to succeed. So with these workshops and readings, you have a chance, without a lot of expense, to really see how it works and, hopefully, if it looks productive, you can take it to a regional place, and try it out, and get all that reaction, and work out the kinks. At this point, I think that most producers do that because it’s an opportunity to make sure the product that they bring to New York, where the critics can be very tough, is as strong as possible.

“Come From Away” certainly went that route. It was workshopped in 2012, and then first produced at Sheridan College in Oakville, Ontario the following year.

Oh, yes.

After a showcase for investors in New York, “Come From Away” had record-breaking runs at the La Jolla Playhouse, the Seattle Repertory Theatre, Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., and the Royal Alexandra Theatre in Toronto. All of which allowed development of the musical while racking up outstanding reviews.

People ask what does it take to make a successful musical, and I respond, “There is no blueprint for it” because I remember when someone mentioned that Lin-Manuel (Miranda) was working on a musical of “Hamilton,” and I thought, “A musical about Alexander Hamilton. How could that really be?” I think that 99% of people would have felt the same way. The same with “Come From Away.” I remember hearing four or five years ago that somebody was writing a musical about the events of September 11th…..

Set in Gander, Newfoundland with 38 planeloads of people stranded there after 9/11.

Set in Gander, right. Set in Gander, Newfoundland. Again, it was like, “A song and dance musical about September 11th? “I can’t quite imagine what that is going to be.” Again, it just shows you that there are people who are just brilliantly creative, who can find a story that touches people, that moves and excites people.

[For the week after passenger planes were hijacked by terrorists and flown into the Twin Towers in Manhattan, and the Pentagon in Washington, Gander–which had a population just under 10,000 at the time–nearly doubled in size. About 6,600 stranded passengers from around the world were housed in guest bedrooms, on pullout couches, and on mats on floors of town halls and schools. Among the refugees were the mayor of Frankfurt, a designer for Hugo Boss, 90 Wish Kids on their way to Disneyland, and a pair of bonobo (pygmy) chimpanzee en route to an Ohio zoo.]

Toronto lawyer Michael Rubinoff, the Associate Dean of Visual and Performing Arts at Sheridan College in Oakville, Ontario teamed up with a Canadian couple, playwright/ songwriter David Hein, and actress/singer Irene Sankoff. Armed with a $12,000 grant from the Canada Council, they headed to Gander for a Sept. 11th, 2011 gathering commemorating the 10th anniversary of the events following 9/11 in 2001 in order to interview locals and “come from aways” returning there.

I started getting involved with the show after the La Jolla run. They had done something at the Seattle Rep (Seattle Repertory Theatre), and then La Jolla. It became clear that this was something special, and that they were going towards Broadway, so they brought me in. A lot of shows take a lot of development over time, and certainly, they continued to work on it, but when I spoke with people who were involved at the beginning, they knew that it was something special right from the start. They knew right away that this was going to be a pretty special piece. What they didn’t know was what the audience reaction was going to be given the climate right now. We found out people want to see a show about humanity, and most people do care and do want to take care of others. This show is the perfect thing to be able to see that right now.

Have you been to Gander?

No, I haven’t. Our company went up to Gander (in 2016) before we came to Broadway. After we finished Toronto, they (140 actors, crew members, producers, and investors) went up to Gander to do two performances in an ice-skating rink for the people there. I wasn’t there, but I was told that the experience there really helped to inform everybody in the Broadway production. It gave them the feel for what the community is like up there and a lot of the people, who the stories are based on, are still there. So it was pretty cool.

My jaw kind of dropped when I heard that an updated film production of “West Side Story” is in the works with a script by Tony Kushner with Steven Spielberg directing. The 1961 film, directed by Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins, is so quintessential. You produced a cast album of “West Side Story” which won a Grammy in 2009, what is your reaction?

I’m incredibly excited because it is, to me, maybe the greatest score that has ever been written for a musical theatre piece. That’s my personal belief.

Look at the talent involved–music by Leonard Bernstein, and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, whose songs for the show are some of the best-known in musical theatre history.

Exactly, and the music was groundbreaking then, and it is still groundbreaking now. It still is a one of a kind thing. It is a little bit scary because that movie production is such an iconic thing. It’s always a bit of a scary proposition to do that (update a film) but, other than that, I feel that this will allow a new generation to witness the musical. In similar situations, where a show or a movie version may not have been seen for the first time, sometimes it’s a way of introducing it to a new audience. So I am hoping that it will be something spectacular.

What’s intriguing about “West Side Story” is that it was so different for the time and that it remains so relevant today. It’s neither a concept musical nor a mega-musical. Also, the book itself is controlled by theme and metaphor. It is totally different than anything out there.

Absolutely. And I was fortunate to be able to produce a cast album of the revival in 2009. I was with Sid Ramin (Broadway and film orchestrations for the musical were by Ramin, Leonard Bernstein, and Irwin Kostal) sitting behind me, and I was able to ask him, “How did this come about?” One of the most interesting things to me was—it’s a very unusual orchestration with that score. There are no violas. If I recall I think that there might be 6 or 7 violins, and 4 cellos So I remember that when I first conducted some of the music, I thought, “This is brilliant that Bernstein thought, “Okay instead of violas I want to stretch the cellos.” That tension that happens when you permit the cellos to play high on the neck. So I asked Sid, “Can you tell me about the decision regarding the use of cellos instead of violas in order to have such a big viola section. He said, “Well, it was simple”–I’m not totally sure that I have the facts right in terms of the theatre—“but when this show was at the Winter Garden back in the day (in 1957) you had certain musicians assigned to certain theaters and, to be perfectly blunt, there were musicians at the theatre that Bernstein was not fond of. So he just wrote around them. That’s how it happened.”

Sondheim, of course, went on to author such musicals as “Sweeney Todd,” “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” “Into the Woods,” “Company,” “Sunday in the Park with George,” “Assassins” and “Follies.” Looking back at his work on “West Side Story,” and despite 8 Tony Awards, two Grammys, a Pulitzer Prize, and an Oscar, he has said that he’s embarrassed by his lyrics for “West Side Story,” and that he hates to hear “I Feel Pretty.” “The street girl is singing, ‘It’s alarming how charming I feel.’ … I just put my head under my wing and pretend I’m not there.”

I wonder what he thought about the Spanish translation in the (2009) revival production that Lin-Manuel Miranda did. I think that they used it for a few months and realized that enough audience members were complaining that because they didn’t speak Spanish they didn’t understand what was going on. They ultimately went back.

In the 2009 Broadway revival of “West Side Story,” with the show’s original director Arthur Laurents who also wrote the book, Lin-Manuel Miranda translated some English lyrics by Stephen Sondheim into Spanish, as part of a greater attempt at authenticity for the Puerto Rican characters. Six months after opening some of the lyrics for “A Boy Like That” and “I Feel Pretty” were changed back to the original English. However, the Spanish lyrics in “Tonight” (“Esta Noche”), as sung by the Sharks, remained in Spanish.]

Interestingly, many musical-based albums in the ‘50s and ‘60s stayed on the Billboard album chart for months and months, particularly film soundtracks. The original 1958 Broadway cast album of “West Side Story” charted for 191 weeks and reached #5; while the 1961 film soundtrack charted for 194 weeks, staying at #1 for an astounding 54 weeks. The 1958 soundtrack album of “South Pacific” charted for 262 weeks, staying at #1 for 31 weeks; while the 1956 film soundtrack of “King and I” charted for 266 weeks, and reached #1.

What has it been like to work on productions of such iconic musicals as “South Pacific,” “West Side Story,” “The King and I,” and now “My Fair Lady” which has just opened at the Lincoln Center Theater under the direction of Bartlett Sher? This marks his third musical revival to play the Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater, following “South Pacific,” and “The King and I” which you also worked on?

Well, I not only worked on those iconic shows, but I have also have been able to work within the confines of The Lincoln Center Theatre.

You have been involved there for almost a decade now.

Yeah. I think that the first production that I did as a contractor was “South Pacific” (2008). Actually, that was the first and only revival on Broadway of “South Pacific.” The thing that is really good about (director) Bartlett Sher and (musical director) Ted Sperling’s casting is that they find people who inhabit the roles, and who are inevitably the people (the characters). I just remember the sitzprobe (a German term used in opera and musical theatre to describe a seated rehearsal where the singers sing with the orchestra) for “South Pacific” where the opening, “Da da da da” with the French horns playing, I just wept, right away. The instant. My whole life, I felt like it was, “Now I am fulfilled. This is one of the magical moments that I will never forget.” I remember also at the time that the girl who was singing “Bali Ha’i,” (Loretta Ables Sayre), by the end she was completely crying. Somebody asked her if she was okay, and she said, I have never sung with an orchestra before. It is just overwhelming to me.” There were so many special moments in doing that production

[Loretta Ables Sayre’s Broadway debut was as Bloody Mary in “South Pacific.” She was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Supporting Actress, and won the 2008 Theatre World Award.]

The Lincoln Center Theatre, because they take such great care, and they are fortunate that they are a non-profit, they are not posting completely on the bottom line. They do try to do things that they feel are artistically…they will always try to satisfy the artistic needs within reason. The same thing with “My Fair Lady”…

As I said, “My Fair Lady” has just opened (on Thurs. March 15th)

Right. Typical of The Lincoln Centre Theatre, Bartlett Sher and Ted Sperling, the care for the music and the storytelling, and the detail, and I just feel so blessed to be a small part of it.

You mentioned the intro overture of “South Pacific.” Many classic Broadway musicals from the mid-50s to the late ‘60s had memorable hooks in their music. Give most people a couple of bars of songs from “South Pacific” or “My Fair Lady” and they can name the song. They are as hook-laden as any classic pop hit.

You still have that. Look at “My Fair Lady” and I can definitely do “bup bup bup bup,” and you know what it is. “I Could Have Danced All Night.” The intros are as important as the hook, as the chorus. I appreciate all kinds of songwriting, but the songwriting back then, the hooks–if you will–were also in the orchestrations. It is just not an intro to a song, it sets the tone for what the piece is going to be.

You have worked on tours of musicals throughout the U.S. That’s a different type of venture than Broadway runs in terms of audience draws and economic scales. Shows might only be running for a week, maybe 6 weeks, and tops 8. The revenue is more limited on the road because most of the shows go into subscription houses with set guarantees whereas producers of a massive hit like “Hamilton” can negotiate a much larger take of box office receipts because the venues are selling tickets for their entire season on the back of the big hit.

Absolutely. The point you make about the economics is that you are playing in a 1,000 seat house here in New York, but you are playing in a 4,000 seat houses in places like Atlanta, and St. Louis. So the economics are completely different. it‘s always interesting to see how a show does in a much bigger venue, and how they (the company) adapts to it. A great director can figure out how to deal with the scale, and make it work, but it’s an interesting challenge. Then, on the music side, it’s interesting too because often we are traveling as a group, but we are picking up musicians in every city. So we have to figure out how do we set it up in a way that we are picking up 13 musicians in every city that we go to, and how can we make sure we present the quality of show that we always want to do?

Does that mean hiring a local contractor?

Yes, I would interface with a local contractor. Most of the contractors I work with I’ve worked with over the years so I tend to work with a lot of players in every city. So when I visit another (new) city, I can talk to them about who would be appropriate for the show. I try to give them an idea of what the music is like because the musicians you are looking for will be quite different.

Ever sat in the orchestra pit one night and wondered, “What the hell are these people I’ve hired playing?”

Yes, there have been times. It is just a function of who is available. If you are going to a small city, there might not even be a symphony orchestra. They are unable to attract the musicians because they don’t have jobs to offer them. So it depends.

With a national touring show do you work with fewer musicians than being in New York or do you work with different arrangements? It’s not likely going to be exactly what you’d see on Broadway.

Well, the production values of a national touring show are pretty phenomenal. They really do attempt to make it as good as the Broadway company. As good as the Broadway production. Obviously, because they are moving from city to city sometimes there are sacrifices, but I can tell you that with “Phantom,” yeah there were some things that were changed, and ultimately some of those things were put back into the New York company because they worked better. There is never the thought of, “We are doing a “B” level version of our show.” It is always an attempt to try to keep the production values as high as possible.

Now on the music side, because of the logistics, you can’t bring a 29-person orchestra for “South Pacific” all around the country, but I think we still ended up doing a 23-person orchestra. So we try to keep those values as high as we can. I think that was one of the big productions of a show on a tour in many, many years. But for some shows, you do a reduction. The economics don’t allow us to bring as big of an orchestra. You do some re-configuration, some re-orchestrating using synthesizers for support. But there are some shows also you will see on the road with the exact same band that you will see here in New York in terms of the instrumentation.

Branded name shows I’m told do better on the road. Being a recognizable title, it’s easier to attract ticket buyers.

Yes. I’m not a theatrical producer, but there’s no question about that. If the intention of the producer is to bring the show on the road, they want to make sure that the show in New York has really established itself because people who are not in New York want to see things that they know are good or have heard of. So it’s very hard to deal with a progressive new piece unless you are at the Old Globe Theatre or La Jolla. Someplace that has a very established reputation. With most of the heartland productions going to Fayetteville or to Austin or wherever, people want to see things that they know are good.

You began working in artist management when the legendary nightclub and concert booker, bandleader, and producer Jerry Kravat recruited you to work at Park Avenue Talent, the production arm of Jerry Kravat Entertainment Services. There you worked with such artists as Barbara Cook, Kelli O’Hara, Paulo Szot, Eldar Djangirov, and Sutton Foster.

Yes. I was at Park Avenue Talent. Then I co-founded Park Avenue Artists in 2011 with Kirk Yano and Ross Michaels. Then IMG came calling for me to work with Joshua Bell, Itzhak (Perlman), Time for Three and Renée Fleming. I kept Park Avenue Artists going for non-classical artists with IMG’s okay. Then, when I left IMG in 2015, Josh and Time For Three came with me.

How much staff do you have at Park Avenue Artists?

We have 5 full-time people. Even then, we are a bit stretched because if you really explore everything you could do with one of these artists, you can work 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. There’s always things to explore. For every one thing that we achieve, there are probably 20 things that we have investigated that haven’t ended up as anything at that moment. We’ve learned so much from our artists. We’ve learned that every artist is different. That sounds obvious but I think that a lot of people try to follow a formula. “We’re going to do this social media stuff. We are going to try to introduce you to the label person. Sign with a record label.” With Yebba, for example, the art and what she wants to do contains everything. Her level of excellence is the same as it is with Josh. Nothing goes out unless she feels it is excellent. And there’s nothing more fulfilling than that.

You’ve worked with Joshua Bell since the days…

When I worked at Sony. That’s right. That’s where we met. Of course, I knew who he was, and had seen him in concert many times and I knew his albums. So that’s where we first met. I think I started with him with his “Voice of the Violin” (2006) project.

As senior VP of A&R at Sony, you produced soundtracks of “South Pacific,” West Side Story,” “Grease,” “Allegro,” and “The Wedding Singer.”

That’s right. It was a fantastic opportunity. I was really there for three years running the A&R operation. During that period of time, most of the things I signed were soundtracks and cast albums.

This was Sony Masterworks?

When I was there it was Sony Classical, and then we changed the name to Sony Masterworks a year into it.

Sony Masterworks has since broadened its scope to include artists ranging from 2Cellos to Yo-Yo Mama to Sonny Rollins to Boyz II Men.

Obviously, the core of the classical business is challenging right now. When I was there, even then it was challenging, but we were fortunate to have Yo-Yo (Ma) and Joshua on the roster. I got to work with some incredible people. Not just with the signed acts but with incredible guest artists that they wanted to work with because part of the mission while I was there was to help come up with interesting ideas to broaden artist’s appeal. Try to develop a broader audience for them and get more people to know who they were. So with Yo-Yo, we did “Songs of Joy and Peace” (2008). That was really a time to think about the artists that he would like to work with. Ultimately, he came up with a Christmas album, but it was more of an inspirational album because it’s not necessarily specific to the (holiday) time period. He got to work with Chris Thile, Renée Fleming and Alison Krauss. All of these artists that are great artists in their own right in what they do. It was part of the biggest thrill for me was being able to see, and learn from what these artists do.

[“Songs of Joy and Peace” won the 2010 Grammy Award for Best Classical Crossover Album. It features collaborations with many other artists, including vocalists Diana Krall, Alison Krauss, James Taylor and Renée Fleming; bassists John Clayton, Edgar Meyer and Nilson Matta; pianists Dave Brubeck, and Robert Hurst; cellist Matt Brubeck, clarinetist Paquito D’Rivera, trumpeter Chris Botti, drummer Billy Kilson, and guitarist Romero Lubambo, mandolinist Chris Thile, fiddler Natalie MacMaster, harpist Marta Cook, saxophonist Joshua Redman, piper Cristina Pato, the Assad Family, ukulele virtuoso Jake Shimabukuro, and Wu Tong and the Silk Road Ensemble.]

So fast forward a few years and we have you to blame for 2Cellos covering AC/DC’s “Highway To Hell” with guitarist Steve Vai for their 2013 album “In2ition?” At what point did you get involved in the management of the Croatian duo of Stjepan Hauser and Luka Šulić?

That would have been early 2011 to early 2012. Our business partner at the time was Kirk Yano who is an amazing engineer. He is one of the great networkers I know. He knows everybody out there. He, Ross and I started the company but Kirk left a year or so into it. A friend of Kirk’s in Croatia said, “I want you to meet these two cellists. They put up a video (on YouTube) of ‘Smooth Criminal,’ the Michael Jackson song, and it’s gone bonkers. It’s got two million views already. I need somebody to help manage them because I don’t know what to do.” So that’s how we ended up managing them. That’s how Park Avenue Artists was started. At the time, we were independent guys. We brought them to Sony Masterworks and that’s how the whole thing happened. We were involved with the first record (the self-titled debut studio album which peaked at #1 on Billboard’s Top Classical Albums chart) and then they started touring with Elton John (including performing at his Las Vegas residencies). That was an amazing time.

Then they ended up switching over to Elton’s management company Rocket Music Management.

Of course, Elton wanted to make sure that these guys were part of his organization. That was a good thing for all of us.

He took them on the road for over two years.

Yes for over two years. In fact, I went to see them in Saratoga. It was pretty thrilling watching them. These two guys from Croatia, who six months before were struggling classical musicians, and were now playing with Elton John to 15,000 people. An incredible thing.

Were Stjepan and Luka concerned about keeping their credibility in the classical space? it is difficult to return to the core classical world if you are not taken seriously there. Classical people don’t favor artists jumping from classical into pop or rock and back to classical.

Yes, for sure. There are 284 hardcore classical fans who will pooh-pooh anything that touches remotely on anything other than core classical. So that’s the perspective that I have. Look, I’m fortunate having gone to work with Joshua, Itzhak and Reneé and others like that who have paid their dues. They have established themselves as the very best at what they do. They have the license to say, “What is it that I like to do?” and go ahead and do it because they have created themselves. Whereas, if you have young artists like 2Cellos, I remember some of the conversations that we would have. They were having great fun doing these amazing arrangements of things, but it can be harder for them to break into the classical world because people would not…they are incredible musicians, let me say that. Top-notch classical players. But there will be an inherent bias because people in the core classical world will not take them seriously, and think that these guys are true classical musicians when, in fact, they are incredibly great, and very serious musicians. So yes, it’s an unfortunate bias. That’s the part of the classical business that I really despise I think music is something to embrace. All kinds of music are great, and I love the diversity and there’s nothing that we should do that should discourage people from exploring music that they like.

At the same time it is difficult to sell music in the classical genre.

Very hard.

There are certain classical artists who still do well like South African violinist Daniel Hope. But some see the crossing of musical genres as a dumbing down of classical music.

Yeah. There is no question that in the past 20 years that there was a time that classical musicians were doing—for a better word Muzaky type of stuff–and that would appeal to more mature audiences, but I think that world has gone. I don’t think that you see great classical instrumentalists trying to do stuff like that with classical. I don’t think that succeeds anymore.

It’ll be interesting to see how Deutsche Grammophon fares with its newest signing, Danish singer/instrumentalist Agnes Obel. She’s already a multi-platinum artist. Her tracks have been streamed over 160 million times on Spotify alone, and her music has been featured in television productions, and films.

I guess my feeling about that (commercial crossover) stems from getting to work with people like Joshua and Itzhak in that when we talk about projects we aren’t as driven by the label–“We need something that is a commercial that we can market and, maybe, get on radio.” Now we just talk about what are the musical things that they want to do that are beyond the core world from a creative standpoint? For example, Josh has always had an interest in music from South America. When President Obama asked him to go to Cuba in 2016 (on a 4-day trip) with a delegation with Smokey Robinson, Dave Matthews, Usher, and actress Alfre Woodard (organized by the President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities), Joshua came back, and said, “This was an extraordinary experience. I got to work with some of the musicians there. The passion and the care for the music there is just an incredible thing.” So we decided to bring charts, and produce a show that was ultimately booked at the Lincoln Center which agreed to bring some of these iconic (Cuba) musicians to New York to do the concert, and for Joshua to be able to play with them. It wasn’t a matter of trying to find a crossover classical project. It was more of a musical collaboration; something that he really wanted to do; and we were able to bring it here, and share it on PBS.

[The “Seasons of Cuba” concert in 2016 featured the Chamber Orchestra of Havana, with pianist/composer Aldo López-Gavilán, singer-songwriter Carlos Varela, and soprano Larisa Martínez. Special guest Dave Matthews.]

You continue to work with Itzhak Perlman?

Well, I still do some consulting work for Itzhak. When my colleague Charlotte Lee and I worked at IMG Artists we were co-managing Itzhak. So when we both left within a month of each other, Mr. Perlman said, “Yes, I would like for you guys to continue to oversee my career.” So Charlotte does his day-to-day as president and founder of Primo Artists. But Itzhak has asked me to stay involved because I am like the old man. “I want someone who has a lot of experience and who is an old guy and who can relate to me.” So I help out with a lot of special projects and Charlotte does the day-to-day.

The company’s roster includes a number of emerging acts including the symphony attractions, singers Ryan Silverman and Ashley Brown; and the singer/songwriters Yebba, Mia Gladstone and Marco Foster. Better-known are Time For Three, the chamber group Windsync, and Australian saxophonist Amy Dickson. How are you and Ross shaping the company?

Both Ross and are cursed by the fact that we like a lot of different kinds of music. We will say first that we are not masters of everything but we love and appreciate a lot of music. When I was working at IMG, I was working with primarily classical artists. Fortunately, I was working with some great ones. It was a fulfilling job, but I felt like I was losing touch with other forms of music because working all day long you are working on specific things. I felt a little bit out of touch with music as a whole. So when Ross and I decided to venture out and start the company, we decided to do music that we really liked, and with artists that we really like.

You and Ross are really gambling working with so many emerging acts.

I really love artist development—unfortunately, it’s not the best thing in terms of making a profit but we gather so much satisfaction out of working with young artists. Every little achievement means so much to us. It may not show up in terms of money but seeing artists like her get their song placed for the first time or seeing artists perform for the first time and get a positive response I can’t tell you how thrilling that is.

Working with emerging acts is a bigger challenge than with established performers.

But it’s amazing how much overlap that there is. You would be surprised by how many conversations we have about Yebba that will somehow morph into a conversation about Joshua Bell, although they are in different genres. We intentionally decided to take on all of these different styles of music knowing that, perhaps, it might spread us a little thin, and it also might make us look a little unfocused. I joke that I have adult ADD, but I’ve accepted that. I like all kinds of different music. The one thing that they (these artists) all have in common is that they are really passionate about the music that they do. For example, with Yebba, we weren’t actually looking for an artist at that point. This was about two years ago, but a colleague sent us a video of her just doing some riffs and things. You could tell from this little clip that this person has some incredible instincts and incredible musicality. We reached out to her. She’s from West Memphis, Arkansas. She had been approached by so many people in the business. The only reason her and her family responded to us was Joshua Bell. Yebba had grown up playing the violin, and her dad said, “This is what we should do. These guys must be real because they work with the great Joshua Bell.” It’s been an incredible journey with her.

I know of Yebba because of her “Evergreen” track which has over 2.8 million plays on Spotify.

Of course.

How did you and Ross meet? I recall him as head of studio operations at Planet2Planet Studios in Manhattan, and that he worked with Flo Rida. He wears as many job hats as you do.

He wears a lot of hats. We met each other at Planet2Planet which was in the Music Building at 251 West 30th which is now condominiums. Planet2Planet Studios was in the basement of that building. It was where the Village People recorded all of their hits. As soon as you walked in the door, you could smell the weed coming out from the walls. It was a catacomb of 8 rooms with different levels of recording happening. I think I was working on an Eldar Djangirov project, the jazz pianist. I was doing some editing there. That’s where we recorded part of Eldar’s “re-imagination” album (2007). Ross was a hip-hop producer. He describes himself as a B or C level producer doing demos of artists that will never become successful. But sometimes those are the people that you learn the most from. I’ve learned so much from artists that have never had a commercial release. They had it (skills) because they had to do things on a limited budget. That is where you really cut your teeth.

Some producer’s best work has been done on a 4-track TEAC recorder.

Oh yeah, I had a 4-track TEAC, and I learned so much from that. You are bringing me back to my college days.

And then you’d transfer tracks to a Studer-Revox A-77 with 10 ½ inch reels.

Exactly. When I was getting busy recording there was a Revox 348. It was amazing technology. I listen back now to some of the stuff that I did then, “Man, this stuff is crunchy.” It was a different time period.

What synth were you using back when you started? The Yamaha DX7, or the Korg Poly800, or a Roland JX-3P?

My very first instrument when I started out was a Roland JX-3P

Roland’s first MIDI synth.

That would have been in ‘82 or ’83. Then I bought a Yamaha DX7.

That was like moving uptown.

I was a big Chick Corea fan. A big Return to Forever fan. Of course, Chick was playing that Moog Reverberator so when I went back to Albany, New York for a summer break in college I went to the only place that had gear in that area, and they had a Moog Reverberator. I spent $500 to have a Moog Reverberator which was a ton of money for me back then. I used it in college at The Underground, the club for music at Brown University. I couldn’t play it all that well, but I figured I had the same thing that Chick Corea had. Thirty years later, we were working on a Christmas album with Josh (“Joshua Bell Musical Gifts from Joshua Bell and Friends” in 2013), and I got to work with Chick on a version of “Greensleeves” with Josh which was amazing.

Atlantic Records Chairman/CEO Craig Kallman went to Brown University around the time you were there.

I think he was a year behind me. He was like the cool guy. He was a DJ. I was playing in a jazz fusion band so I was about as uncool as you could be. He was like Mr. Cool. I went to (Tommy Boy Entertainment) Tom Silverman’s 50th birthday party and, Craig was DJ-ing.

[Craig Kallman began his music industry career while still a teenager, DJ-ing at the Cat Club in New York while working in Columbia Records’ dance department. At Brown University, he was a CBS Records college representative.]

When did you start playing piano?

At a very young age. I can’t remember not playing the piano. When I was 6, my piano teacher said you should meet my teacher in New York at the Juilliard School (pianist and instructor) Adele Marcus who taught Byron Janis.

And taught Neil Sedaka by the way. Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Troy, New York about 150 miles upstate (from Manhattan). I felt very isolated as a pianist growing up in Troy. There weren’t a lot of people doing classical music. I suddenly realized “Wow, who are those people who love chamber music?” That’s when I really started getting involved in what I thought was becoming a musician, although by the time that I got to high school I knew that I was not going to be a great classical pianist. That I wasn’t going to be good enough to be a classical musician. But playing allowed me to love music.

You had a 15 year run at Sony Music in business affairs.

I always thought that what would be great was to somehow combine my business interests and my music interests.

C’mon David, you received BAs in Engineering, Economics, and Music from Brown University, and an MBA in Finance and Marketing from Columbia University. A bit of an overachiever?

Yeah, but I kind of knew that…First of all, I would describe myself as someone who is reasonably competent at a lot of things, but I wouldn’t describe myself as a master of anything. Because of that, I like to learn and do a lot of different things. So the record business, when I joined back in 1989, I felt it would give me the opportunity to combine my interest in the business side as much as music.

Between four years of studying for the BAs and two years to get an MBA, you seemed to be on your way to becoming a professional student. I can hear your father saying, “David, when are you going to start working?”

Well, it’s funny that you mention that because the only reason I went to Columbia for business school was because my father was given a dual appointment as professor for Mechanical Engineering and Biomechanics at Columbia for a couple of years. This was right after I graduated from undergrad. As long as he was there I could go to school for free. I was in Providence working at a bank for a year and it was fine, but I transferred there and I said, “Dad, you are going to be teaching there for two years? Okay, let me see, what kind of two-year program should I do. Oh, I will do an MBA. Why not if I can get in?” So that’s the only reason that I got an MBA there. It definitely led me into the music business because while I was there—actually a friend of mine who was a cello teacher at Brown; I used to play for his students—he said to me, “When you are in New York you should look up a friend of mine.” I was starting business school, “Nahh. I’m going to get serious. I’m going to let music go. I’m going to focus on business, and I’m going to end up being a banker or an advertising account executive” or who knows what I was going to do. But then I went to see the “The Phantom of the Opera” in 1983, and I met this woman, Kristen Blodgette, who was in the program as one of the pianists. I introduced myself to her. To make a long story short, that’s how I got pulled back into the music business as a performer, subbing for her on the piano book and then, ultimately, in producing and management.

Who was then playing the Phantom, Michael Crawford?

Yes, it was Michael Crawford.

Your background as a musician, as a contractor, and as a record producer coupled with your business acumen no doubt provides you with the ability to deal with artists.

I feel very fortunate in regards to working as a musician in the Broadway pit in that I can understand what is important to artists. Working with a lot of Broadway singers. Every artist is different, but artists are artists. You need to understand what is important, and what are the things that mean the most to them. Then on the business side, from working at Sony, first in business affairs, and then running the operations for Sony Masterworks, I think I understand from the business side what is important to them. I’m fortunate to be in the middle where I can kind of understand the sensitivities of both sides, and try to find a lane for an artist and a project in the context of running a business.

For so many artists the business aspects of their careers are to be avoided, but with the downsizing of labels in recent years many are being forced to be both creative and business people. Some have not been able to do that.

Well, the thing that is exciting about this time is that because of the industry, artists have had to re-invent the way the business works on the recording side. You are hearing so many records that record labels probably once would have dismissed or said, “No this is not going to be popular or successful.” I look at a group like Vulfpeck. They don’t really have management. They don’t have a label and they will sell out the Brooklyn Theatre over four nights. That’s 2,800 people. I don’t know if they would have been given that opportunity 10 years ago because there wouldn’t be the opportunity to do it themselves. As a musical audience person, I think the situation now is better than ever. Now people are really able to create their art. They are able to get it out. The challenge now is marketing it so it will get to an audience that will appreciate it. But at least they can get their music out. The barriers to entry are pretty much gone if you are really motivated to do something. That is pretty exciting.

The Time’s Up movement, and the #MeToo campaign, both exposing the deep-seated issue of sexual harassment, have also impacted the Broadway community. Recently, Justin Huff, who cast such shows as “Kinky Boots,” “On Your Feet!,” “The Color Purple,” and “Newsies” was terminated by Telsey + Co. after allegations against him of sexual misconduct. While Actors’ Equity and The Society of Stage Directors and Choreographers Society have policies in place to report harassment, producers, directors, casting directors, and musician contractors hold considerable power over actors and musicians. There is certainly a chill in all of the entertainment sectors right now.

No question. Not just in the music business, but it’s with everything. It doesn’t matter what industry you are in. Does it make me act any differently than I used to? I don’t think so. I’ve always prided myself on trying to find the people who are the best fit for the job. But I do think about, especially in the theatre, it’s a much more touchy-feely thing. When you have actors onstage acting out the roles and physically having to be involved, it’s a different thing. I know what my intentions are so I’m comfortable with that. If I was 25 and coming into this business, I would be much cognizant than when I was 25. When I was 25 I didn’t think anything about giving somebody a hug. It would never occur to me that it would be misinterpreted. So while I’m not going to the extreme of being careful to interview somebody without someone else in the room, I’m careful not to say anything that could be misconstrued as anything other than what is appropriate. I am also cognizant that when I’m in the theatre community it is much more open. I hug my friends both male and female in the theatre business. In other situations, I’m aware of what the culture is of the particular industry or whatever that setting is. So you have to be more cognizant of it (these issues) because it can be misread

In theatre, any actor or singer can be turned down within seconds for a gesture, a mannerism, or their voice.

They are constantly judged. In open calls, you have people sing 16 bars in 15 seconds. I used to think that was so inhumane; I still do, but if you have 300 people auditioning and you have to filter down to the two people that you are looking for, there’s no other way to do it, unless you want to be there for a week.

Larry LeBlanc is widely recognized as one of the leading music industry journalists in the world. Before joining CelebrityAccess in 2008 as senior editor, he was the Canadian bureau chief of Billboard from 1991-2007 and Canadian editor of Record World from 1970-80. He was also a co-founder of the late Canadian music trade, The Record. He has been quoted on music industry issues in hundreds of publications including Time, Forbes, and the London Times. He is co-author of the book “Music From Far And Wide.”

He is the recipient of the 2013 Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award, recognizing individuals who have made an impact on the Canadian music industry.