SAN FRANCISCO (Hypebot) – As YouTube turns 10 years old today, Google is putting the finishing touches on an on-demand music streaming service as an add on to its video service. With Spotify, Apple, Deezer and others. With YouTube’s significant foothold in the industry, a YouTube streaming service seemed almost inevitable.

Guest Post by Griffin Davis from Berklee College of Music's Music Business Journal

In mid-July 2014, Google began reserving a whole slew of urls related to the name YouTube Music Key, then a little over a month later screenshots of the Music Key Android app were leaked, and it was confirmed that YouTube’s new service would be a subscription-based, on-demand service. As with many subscription services, Music Key will be free of advertisements, and will offer an offline listening mode. Additionally, because of YouTube’s prominence in video streaming, users will be able to either watch the music video associated with a song, or just listen with the services “audio-only” mode.

With Music Key, Google will now have a rather impressive line of streaming services. Of course YouTube’s video streaming service will remain the centerpiece of their offerings, and will remain unchanged with the exception of the recently added music page, which functions more as an aggregator for music videos from YouTube and Vevo than as a new service. Where things get a bit murky is in distinguishing between Music Key and Google’s existing music service, Google Play Music. While there are some differences between the two services, such as Google Play Music’s function as a music locker, users need not worry about which service is best for them, as a subscription to either will include access to the other.

Indie Pains

While the name and exact nature of YouTube’s new streaming service weren’t announced until the middle of the summer, the major buzz around it started in late spring, though not in the way YouTube likely hoped. The conversation began when news broke that independent record labels were very unhappy with the deal offered to them by YouTube for their upcoming streaming service. The deal was offered to the indies after YouTube had spent time negotiating and ultimately signing deals with all three major labels. It was not an invitation to begin negotiations, but rather a “take it or leave it” contract, with the penalty for leaving it being exclusion from the new service.

While exclusion may sound somewhat harsh, it is in fact the only option for YouTube, as including indie label controlled recordings without a license would be a rather glaring case of copyright infringement. It is also important to note that this is not the first time indie labels have been offered a “take it or leave it” contract. Apple, for example, famously proposed such a deal with iTunes Radio. While indie labels agreed to the Apple deal, they found the terms of the contract, which included a variant on a most favored nations clause allowing YouTube to lower royalty rates for the indies should the major labels agree to a lower rate, to be far too unfavorable to agree to. Instead, the labels united behind trade groups Merlin and the Worldwide Independent Network (WIN), releasing several official statements protesting the non-negotiable contracts, and even sought help from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission and the U.K. Secretary of State for Business.

As the conflict became more and more publicized, it was widely reported that YouTube would be taking down the videos of artists signed to labels that refused to accept the deal, sending those sympathetic to the indies labels’ position into a frenzy. The threat of takedowns never came to fruition, though, and after several months of very public conflict, YouTube was able to privately make a deal with the vast majority of independent labels and Merlin. The terms of that deal have not been released.

No Windowing

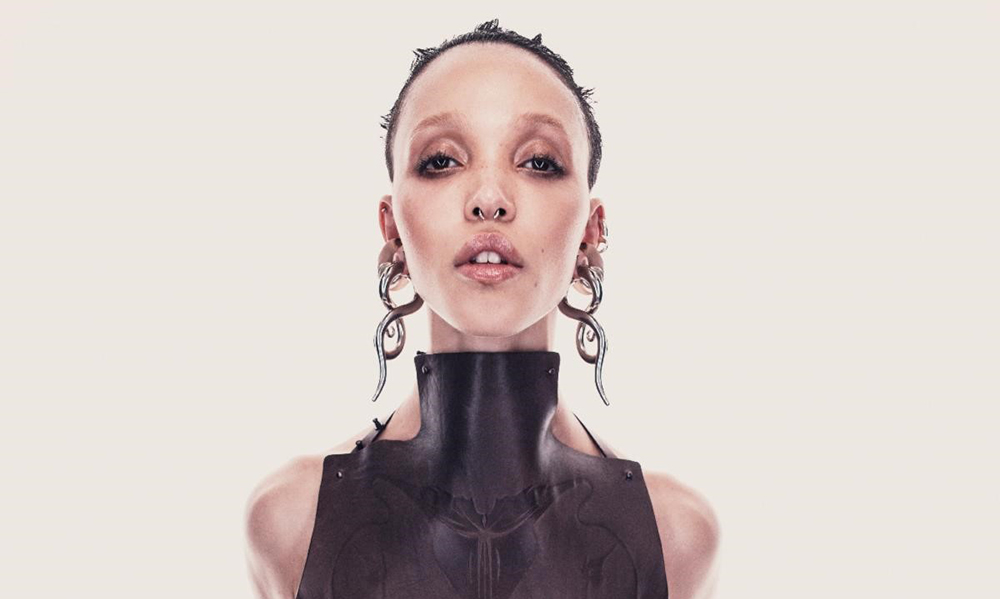

While YouTube was able to strike a deal with independent labels, its conflicts with the independent sector of the music industry were by no means over. On January 22, cellist, composer, and advocate for independent musicians, Zoë Keating released a post on her Tumblr account detailing her concerns about the Music Key deal she was offered and her confusing interactions with her YouTube representative. Among other things, her post claimed the contract required that “All of [her] catalog must be included in both the free and premium music service,” and that her music must be released on YouTube on the same date it is released anywhere else, preventing her from engaging in the fairly common practice, known as windowing, of staggering releases in the hope of bolstering sales.

In an exchange between YouTube employee Matt McLernon and Digital Music News founder Paul Resnikoff, McLernon called Keating’s claims “patently false,” though a transcript posted by Keating of her conversation with her YouTube representative appeared to confirm that the concerns discussed in her blog post were well founded. In the transcript, in response to Keating asking whether she would be allowed to remain in the Content ID program even if she did not license her music for use in Music Key, the YouTube rep’s response was “[that is] unfortunately not an option.”

Money and Rank

Though the uproar ultimately died down in both of YouTube’s conflicts with the independent sector, these problems are indicative of issues with both YouTube and the way licensing is done for on-demand streaming services. For YouTube, part of the reason these conflicts became so inflated was because of the lack of a clear explanation of their different payment mechanisms.

In fact, with the introduction of Music Key, YouTube now has three different monetization mechanisms:

(i) The partner program allows content creators to take a cut of the revenue generated by advertisements on their videos;

(ii) The Content ID program gives members a share of advertising revenue from third party videos containing material that they control the rights to—rights owners can also choose to have the infringing video taken down, or leave it alone completely; and

(iii) Music Key functions like most other on-demand streaming services, with royalty payments being made according to song usage.

A simple clarification would likely have helped clear the tension. The real issue, however, is that the way services negotiate with indie labels is inherently disadvantageous for the labels. When a company is looking to license recordings for a service like Music Key, they always start by negotiating with the major labels who control not only a significant portion of the recordings they need, but also an overwhelming majority of the recordings that receive massive amounts of play, making them significant gatekeepers to having a successful streaming service. Once a service has these three big deals in place, they now have a viable catalog of offerings, leaving indie labels as a sort of nice extra, but not a group that has clout or can bring key value to the table.

Music Key’s Promise

Though Music Key is only in beta testing mode, Google has already endured much negative publicity and not just from the indie label sector. Irving Azoff’s Global Music Rights, a new boutique PRO, controls the performance rights of, among others, Pharrell Williams, The Eagles, and John Lennon. Azoff has claimed that YouTube does not in fact have licenses for the roughly 20,000 songs in GMR’s catalog, and is threatening a billion dollar lawsuit if they are not removed. While there has been some debate over the legal merit of Azoff’s claim, making a powerful enemy of him does not help Music Key’s launch.

Still, bad P.R. is unlikely to be a deterrent to Google’s Music Key. Though YouTube is a bit late to the game and faces fierce competition from well-established services like Spotify and Deezer, Music Key rides the back of a massively popular video streaming service that is used by more than sixty percent of music listeners age 13-25. Music Key is also one of the few entrants to the on-demand streaming market to bring something new, the ability to switch easily between music video and audio-only modes.

Jeff Price, founder of Tunecore and Audiam, believes that the audio-only mode will help YouTube make inroads with older listeners, many of whom are not interested in watching the video that accompanies a music selection. There has also been some good news from beta testing, with the Music Key royalty statement of an independent artist with a major distributor listing a per stream rate of 5.38 cents. Given that Music Key pays royalties based on a percentage of total streams, the royalty rate is likely to go down once the service is open to the public. But it certainly helps to be the only streaming service that does not need to apologize for the rates it pays artists.

By Griffin Davis