This week In the Hot Seat with Larry LeBlanc: David Peck, President Reelin’ In The Years Productions & Photo Archive.

David Peck may be the most valuable American cultural entrepreneur of our time.

The impact of his nonpareil collection of music-related film and TV footage is no less than seismic.

With 30,000 hours of music footage, thousands of hours of in-depth interviews with some of the most important figures in popular culture, and a music photo archive containing over 200,000 images, Reelin’ In The Years Productions & Photo Archive in San Diego, California has carved out its own particular niche.

Peck’s company also represents the rights to all of the music footage held by more than 50 television stations and independent archives throughout Europe, North America and Australia, and is able to license that material to all forms of media.

The music footage library runs the gamut from full-length concerts to in-the-studio live and lip-sync performances as well as interviews, and B-roll footage with artists.

In addition, with its representation of “The Merv Griffin Show,” The Sir David Frost Archive, The Rona Barrett Archive, Canada’s Brian Linehan Archive and numerous other libraries, Reelin’ In The Years Productions is able to license over 7,000 hours of celebrity interviews.

Reelin’ In The Years Productions has also been involved in creating original programs on DVDs though this has been cut short in recent years.

After releasing the in-concert compilation, “Experience Jimi Hendrix” in 2002, Reelin’ In The Years Productions issued four volumes of “The American Folk Blues Festival”; a Motown series with Marvin Gaye, the Temptations, and Smokey Robinson and the Miracles; 36 titles of the “Jazz Icons” series, including sets featuring Duke Ellington, John Coltrane, and Thelonious Monk; the “British Invasion” series featuring documentaries of the Hollies, Dusty Springfield, the Small Faces, Herman’s Hermits, and Gerry and The Pacemakers; and, finally, the spectacular, 12-DVD box set, “The Merv Griffin Show – 1962-1986” in 2014.

Reelin’ In The Years Productions, along with other major music and media companies, is now involved in The Coda Collection, the new music video channel which launched in the United States via Prime Video Channels on February 18th (2021). The channel will roll out globally throughout the rest of 2021.

A warning: Peck’s own skill as a raconteur could fill hours of footage. His enthusiasm is as intense as his focused ambition.

Like many, our family over the holidays watched “The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend A Broken Heart,” the feature documentary which was an official selection of the 2020 Telluride Film Festival before it was scratched by the pandemic. The film premiered on HBO.

A phenomenal film.

For you to have worked on a film directed by Frank Marshall, and to work with the White Horse Pictures production team, headed by Nigel Sinclair, and including Aly Parker, Nick Ferrall, Jeanne Elfant Festa, and Cassidy Hartmann, was all so cool.

From the first cut—there are 6 or 7 different cuts in it—yeah, I was blown away. Of course, it changed a lot, as any documentary does. Things either fell out or sections moved to different parts of the story as they homed in, like you do as you edit. I was so proud to be a part of that film.

Is it the first time that you have received an executive producer credit on a documentary of this stature?

Yeah, as one of the executive producers (along with David Blackman, Nicholas Ferrall, Cassidy Hartman, and Ryan Suffern), and going in, I didn’t know that. That was literally Nigel and Frank saying, “David, you’ve contributed so much to the film, we want to give this to you.” I was like, “Thank you.”

The Bee Gees’ documentary was already underway when you got involved.

So, the fact that I got executive producer (credit) on that when I was not expecting it….as matter of fact it was when they were getting near the first cut that I called them, and said, “Let me take a look at it, and I can let you know.” They said, “Okay, David but understand this is separate from our (recent White Horse Pictures) agreement.” I said, “No no no let me just look at it and see.” So I did (look at it), and I started making suggestions, pointing out little things. They were really appreciative of my suggestions. They took a fair amount of them. When you are in my position, and making suggestions to someone like Frank Marshall the director, and to Nigel, you do it respectively.

I worked more on the White Horse Pictures side of things with Nigel’s team. But Frank, being the director, was obviously on board. I never once spoke with Frank directly, however.

You were obviously quite involved in guiding the “How Can You Mend A Broken Heart” production team to footage, not just in your archive, but to others that you thought would fit, and you offered considerable advice on the historical accuracy of cuts developed In the documentary. In particular, you lobbied long and hard to have the Bee Gees’ archival footage— the 8mm home footage—which had been earlier transferred–but the transfer hadn’t been great—and you said, “I think you have to make another transfer here.”

What happened was from when I saw that first cut. Some of that Bee Gees’ footage had been used in other documentaries, like David Leaf’s 2001 documentary (“This Is Where I Came In”) which is a great documentary by the way. David did a brilliant job, and that was when the three of them (the Gibbs) were alive, and many of the interviews in the film with Maurice and Robin came from stuff David Leaf did back then. But anyway, I saw it, and I said, “This does not look right.”

What was wrong?

Look, 8mm is always prone to the lighting in the room, and all of that. I understand that. That goes without saying. But I saw things that were shot outside, and I was like, “Wait a minute, this doesn’t pop.” I asked, “Where did you get them (the original footage)?” And I was told they got them from a DigiBeta (Digital Betacam, the half-inch professional videocassette developed by Sony in 1993). And I go, “Okay, but we also saw a copy of betas and U-matics (the analogue recording videocassette format).” I said, “Okay, you just answered my question. Here’s what happened. In the ‘80s, somebody transferred those films to U-matic, and later somebody dubbed them to Betacam, and later somebody dubbed them to DigiBeta.” It doesn’t matter because the original source is a poor transfer that was done to U-matic.”

I said to them, “Look, really it’s only 30 seconds—I understand that—but you have used the home movies in such a beautiful way as a narrative that it takes you inside their world. The audience deserves to have it looking the best that it can. No, you don’t have to take out every scratch from every frame—that is a bit over the top—but certainly give them the colors; give them what was there.”

They heard me, but it was like, “I don’t think we can do it.”

Why not?

The problem was that it had been stored at Iron Mountain (the film and music vault near Boyers, Pennsylvania). Even with Universal, and the Bee Gees, it’s not easy to break through that, even if they are part of the project. I was told, “It will be very difficult to do this.”

What then happened?

In the summer of 2019, I’m in L.A. sitting with Aly Parker, who is one of the (supervising) producers. A great lady. We were sitting in the lobby of the hotel that I was at, having coffee or whatever, and I said, “Aly, look I know that I have been on you about this but, I want to tell you something. She said, “okay.” Now, we represent John Byrne Cooke’s estate.

I think he was Janis Joplin’s road manager (publishing the book “On the Road with Janis Joplin” in 2015).

He was Janis Joplin’s road manager for her entire career (from Dec. 1, 1967, until her death). He was the one who sadly found her body (at the Landmark Motor Hotel in Los Angeles on October 4th, 1970). He shot a lot of home movies of Janis on the road. Even some footage of her at the hotel she died at which is really eerie. It could have been days before she died or the day of. I don’t know. It’s her standing in the doorway of the hotel. It’s not the same room (where she died) because the room is facing the pool. But the footage of her, and the Full Tilt Boogie in the pool, it’s eerie.

Anyway, John had his videos transferred in the ‘80s. Once I saw them, I said to the family, “Look, I have to get these films done.” And it just so happened a couple of weeks prior I had them re-done (re-transferred), and I had both of them (the original, and the new version) on my iPad. I said, “Aly, let me show you this footage of Janis coming off a plane in Hawaii.” She’s got the classic Pearl Boa around her neck. Very colorful. And I said, “Now, let me show you when I had the film re-transferred.” She was like, “Oh my God.” I go, “Right. I can guarantee you that a number of the films, if not all, that you re-transfer will pop; 8 mm is not 16mm, I understand that, but there are a lot of colors, and detail in those films that can be brought out with the right transfer.”

A number of weeks or months later, Aly called to say that it was looking so good. So that is one of many things that I felt that I brought to the film. That I can look at and say, “I did that. That was because of me.” And that feels good to be able to point to stuff that the average person didn’t see beforehand so they wouldn’t know. Larry, you working in film understand how different something can look.

So they went back to the original 8mm footage?

That is what I was pushing them to do. Back in the ‘80s when they retransferred it. We have all seen home movies in the ‘80s that were done at Fotomat or wherever. You look at them now, the difference is unbelievable.

Of course, Frank and Nigel had final say with what was done with “How Can You Mend A Broken Heart.” You had to go along with them.

Of course, it’s always, “You make the decision,” but there was one point in the Bee Gees’ film that—I didn’t cross the line—but, I certainly was very, very firm in what I felt needed to be changed, and they did change it. Robin, Barry and Maurice always told this story that Otis Redding had asked them to write a song, and that they wrote “To Love Somebody,” and Otis died, and he couldn’t sing it. So, when I saw the first cut of the film, and that story was in there, I called up, “Guys, this didn’t happen. This is wrong.” I did an Otis Redding film (“Dreams To Remember: The Legacy of Otis Redding”) in 2007, and I went through this thing.

(“Dreams To Remember: The Legacy of Otis Redding” featured 16 vintage Otis TV performances, a new video for “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay,” featuring footage of the boathouse where Redding wrote the song, and interviews with Stax Records founder Jim Stewart, the Memphis Horns’ Wayne Jackson, and Booker T. & The MG’s guitarist Steve Cropper, who talked about receiving the news of Otis’ death.)

It is such a timeless story. Manager Robert Stigwood introducing Barry and Robin to Otis at the Apollo Theater in New York in April 1967, and Barry saying that they wanted to write Otis a song. ’To Love Somebody’ was born that night,” Barry has said many times. But sadly Otis Redding died in December 10th, 1967, and never got to record it.

Yet, days before his death Otis had joined Steve Cropper at the Stax recording studio in Memphis to record “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay.”

Exactly. I was really adamant about that one. I was like, “Guys this is not right. Their memory is wrong.” (From the production team) it was, “No no no. This is a great story.” I was like, “I know it’s a great story, but I’m telling you that it didn’t happen.”

So, I laid it all out for them.

“Okay facts: First of all, Otis Redding did not need anybody writing a song for him. He wrote songs himself or wrote songs with Steve Cropper at the Lorraine Motel (a historic building in Memphis where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated). Anything that was new was written by him or Steve. Virtually every song on Otis’ albums is either a standard like “Old Man River” or he would do a Sam Cooke song like “Chain Gang” or “Shake.” Or, if it was big enough, he’d delve into the rock world, and he did “Satisfaction” and “Day Tripper,” and just killed them. He killed those versions. Made them his own. So if you are looking at Otis Redding meets Barry and Robin at the Apollo Theatre in April of 1967, the Bee Gees had one song out, “New York Mining Disaster 1941, Have You Seen My Wife, Mr. Jones,” (their debut American single, released on April 14, 1967). Why on earth would Otis Redding go to a group whose music sounds nothing like what he was doing? They were not a very big group at that point.

The point is the Bee Gees did not record that song until, I think, May or June (releasing it July 15th in the U.S.), and it hit the charts. Otis was out of commission for most of the summer of ’67 after The Monterey International Pop Music Festival (the three-day concert event held June 16-18, 1967) in order to have his vocal cords repaired. He had nodes on this throat. He came back in the Fall, started to record, and began touring with the Bar-Kays, and died on Dec. 10th (his Beechcraft H18 airplane crashing into Lake Monona, the freshwater drainage lake adjacent to Madison, Wisconsin).

Otis had plenty of time to record “To Love Somebody” if he wanted to.

I’m not saying that Barry didn’t write the song with Otis in mind; that he was inspired by him, but Otis Redding saying, “Can you write me a song?” never rang true, and Otis dying before he had a chance to record it never rang true either because Otis recorded a lot of songs in the last couple months before he died.

With these facts, I find it improbable that Otis Redding ever asked them to write a song for him because one, he didn’t need them, and when Otis met the Bee Gees they were virtually unknown in this country. It’s quite possible based on the timing of the meeting at the Apollo that Barry thought of Otis, and told him he had a great song for him (“To Love Somebody”), and Otis may have said, “I’d love to hear it,” but the Bee Gees story for all these years that he died before he could record, it is not accurate. I don’t think Barry, Robin, or Maurice lied about this, but memory is a funny thing. Sometimes you truly believe something happened a certain way until facts show otherwise. I mean no disrespect to them in doubting this story but I felt very strongly about it when I saw an early cut of the film, and the directors agreed to change it for the film. They recut the scene in the film to fit the narrative of what I just told you. Of course, Barry ultimately approved the film so I’m guessing he saw no problem in the way the story had been changed in the documentary.

(The Bee Gees’ life story is rumored to become a stage musical that is being developed with Barry Gibb, Elisabeth Murdoch, Stacey Snider, and Steven Spielberg. Meanwhile, “Bohemian Rhapsody producer Graham King, and writer Anthony McCarten, best-known for writing “Bohemian Rhapsody,” and the biopics “The Theory of Everything, and “The Two Popes,” are said to be developing a Bee Gees’ narrative film for Paramount.)

In 2018, Reelin’ In The Years Productions, and White Horse Pictures made a multi-picture partnership to create documentaries in the film and TV space.

The two companies had worked piecemeal on nearly a dozen films since 2006 including on the Ron Howard-directed “Amazing Journey: The Story of The Who” (2007), “George Harrison: Living In the Material World,” (2016), “The Beatles: Eight Days A Week — The Touring Years,” (2016), and “Pavarotti” (2019); as well as “The Apollo,” the Roger Ross Williams-directed, HBO documentary which won the Emmy last year for Outstanding Documentary or Non-Fiction Special.

(In the announcement White Horse Pictures’ principal Nigel Sinclair said formalizing the partnership made sense. “Of course, David runs this amazing library, but he also brings to the table the passion and commitment of a true archivist who cares deeply about the historical importance of footage and the need to preserve it. His invaluable advice to us on projects has gone way beyond just curating the footage he represents and this new partnership is a chance for us to utilize his extraordinary knowledge to create some very high-level, archive-driven projects on subjects we all love.”)

Here’s what happened. First of all, my relationships in those previous projects were strictly as a license holder “Hey, we want to use these clips of The Who or Pavarotti,” or whoever. For many years, prior to our relationship to develop projects together, I would license footage to them for various projects they were working on such as “The Who: Amazing Journey,” Living In the Material World” and such. What happened was that after “The Beatles: Eight Days A Week — The Touring Years” that we did, we started to develop a closer relationship. Over time we talked more frequently.

Then around May 2018, Nigel called me, and said, “David, a couple of my top people want to come down to San Diego, and meet with you. We want to talk about working more closely with you.” I was like, “Wow.” When a major producer like Nigel and his team are going to hop in a car and drive from Beverly Hills to San Diego, that’s a big effing deal.

If you get to know me, I’m a pretty humble guy. I have to promote myself, my business, and let people know what I’m doing because that is just part of doing business. But day to day I don’t have a puffed-out chest. Nominated for a Grammy, that’s cool, but I’m no better than anybody else, and I am proud of what I do.

So, I am humbled, realizing the significance of it. But not fully knowing why they want to come down but, “Okay great.”

So, Nigel, Nick who is his president, Jeanne Elfant Festa, and Cassidy Hartmann come down to my office in San Diego . The top people in the company. We are sitting there, and Nigel says to me, “We want to work with you. We want to develop projects around your archives. We want to bring you in to consult with us. To produce with us. Based on projects that will occur.”

My jaw kinda hit the floor because he said, “David, your archive is one thing but your value to a project is even more. Your knowledge of music history. Your knowledge of music footage. What works well. We really value that, and we want to work with you.” Obviously. again and not to be redundant, It was humbling. It was like Wow.” It was an honor. We signed an informal relationship agreement that basically said that as projects come up, it will determine what role I play in them. And the funny thing is the Bee Gees’ documentary was not one of them.

What staff do you work with?

At present, I have two employees who have been working from home for the past year due to COVID-19. Phil Galloway, who has been one of my closest friends since 1985, is my VP. He has worked with me since 2003 when he sold his record store Off The Record which he had owned for 19 years. There’s also Mark DeCerbo whom I’ve known since 1987, who started to work with me in 2007. He’s been a singer/songwriter, and formed many locally successful bands (including Four Eyes), and in 1990 he released a solo album (“Baby’s Not in the Mood”) on Herb Cohen’s Bizarre/Straight label. Mark helps with logging material, and getting footage ready for people to look at for considering on their projects.

You started Reelin’ In The Years in 1992 with what staff?

Just myself. I have to take you back to ’84 because it started as a hobby. I ran into a guy who turned me onto footage of the Stones on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” and it blew my mind. I was 18. I obviously never saw the Stones with Brian Jones because nobody was seeing that. There was nowhere to see any of that stuff. It was very underground. I started trading (footage) with people in the back of Goldmine magazine. I got bit by a bug. True. I wanted to see the Beatles. I remember seeing clips of “Hullabaloo,” and seeing the Zombies and other groups, and going, “I had no idea what they looked like.” And some of them, I’d think, “The song is cool, but they look like dorks.” It (show footage) just fucked up my brain because it wasn’t music videos. Many bands really didn’t have an image. Certain bands, the Stones, and the Beatles did because they were widely seen. Or Dylan had an image. But, for a lot of those bands, their image was what was on their album cover for the most part. So I started doing that (seeking footage).

In 1989, I got a call from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as I started building up a name for myself as this guy who had tons of music footage, that knew where bodies were buried so to speak, or knew who and what. So I got hired to consult. I was 22. A 22-year-old kid working on the fourth Rock Hall of Fame induction (in 1989). At that moment, I went, “Oh, this could be fun. I could make a living out of this.”

Then I started doing more research. But at the same time, I had to eat so I was working at an attorney service. Serving subpoenas, filing out court documents, and driving all over San Diego. At the same time, slowly building this (music footage archive) up in the background.

I can remember using music videos to supplement interviews on CBC-TV’s “Take 30” and CTV’s “Canada AM” in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Snagging footage from Tony Palmer’s 17-part ITV series “All You Need Is Love.” Also I received video clips originally shot for BBC’s “Top of the Pops.” John Martin who conceived CITY-TV’s “The New Music” program in 1979, and then MuchMusic, which launched in 1984, told me that snatching music performances off television or other sources was illegal but everybody was doing it. It was the Wild West. The same when you started Reeling In The Years?

Yep. Oh yeah. At that point I didn’t know anything, right? There’s no footage, and I didn’t own the rights. I saw a lot of other companies out there that had footage but it wasn’t stuff that I thought of representing. I built up an archive of things I did not have the rights to but frequently, from 1990-1998–before I started to represent various rights holders around the globe purchasing archives–I would be contacted for footage that I had copies of; where the rights holder either did not have or could not find their footage. In those cases, I would charge an access fee which meant they would pay for a copy, but would have to clear the rights with the rights holders. To this day, from time to time, I still get calls for items we don’t own but the rights holders don’t have.

How did you come to launch Reelin’ In The Years Productions?

Well, everything changed in January 1998. I was in New York. I had known Paul Shaffer for many, many years. Whenever I was in New York, I was allowed to go to the (David) Letterman show, and I’d usually hang out in the green room. So I was in New York. Well, this was the year that the Eagles, and Santana were inducted at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame ceremonies, and the Stones played Madison Square Gardens. The next night the Spice Girls were going to be on Letterman. I didn’t care about the Spice Girls. However, I had a 9-year-old niece who did. I felt that if I could get their autographs then I would be the coolest uncle on the planet. They happened to be on the cover of Vogue magazine that month. The first time in my life I bought Vogue. So I’m in the green room which is really really small. It’s near the end of the show and somebody comes in, and says, “Everybody out of the room, the Spice Girls are coming in.” So everybody starts to leave. I don’t. I turned to the guy next to me and said, “You lost your car keys. Work me with.” He says, “Yeah, I lost my car keys.” So he’s pretending to look on the floor. The next thing I know the entire group and David Beckham are in there. I go to one of Spice Girls and ask if they’d sign the Vogue cover for my niece. No problem. They all sign it. A few minutes later, “Baby Spice” (Emma Bunton), who was wearing this all-white leather outfit, she goes, “Oh, fuck.” She had smudged the black ink on the cover of Vogue on her hand, and if looks could kill, oh my God. So at this point they have to go on air. She doesn’t have time to wash her hand. They leave the room. and we are kicked out.

Now on Thursday nights Letterman taped two shows. Well, there’s a green room downstairs. So I walk in there and put the magazine on top of the counter to dry, and I see that Sandra Bernhard is in the room, and there’s this guy sitting in a chair. He says, “You are a pretty cool uncle.” I say, “By the way, my name is David Peck, what’s your name? He’s replies, “Chuck Leavall.” It’s Chuck Leavall of the Allman Brothers, and the Rolling Stones. I told him I had footage of him in the Allmans with (bassist) Berry Oakley. He had joined, and Berry Oakley and those guys did “In Concert” (ABC-TV’s late-night series created by Don Kirshner) and a week later Barry died. He said, “Oh my God, I’d love to see it. I’ll pay for it.” I said, “I don’t want your money. Don’t worry about it.”

(On November 11, 1972, Berry Oakley was involved in a motorcycle accident in Macon, Georgia, just three blocks from where the Allman’s guitarist Duane Allman had his fatal motorcycle accident the previous October. Chuck Leavall joined the Allman Brothers in September 1972, when they decided not to recreate their dual lead guitar sound after the death of Duane, but rather to use a different instrument as the second lead.)

As Chuck was leaving to sit in with the (Letterman) band, I said, “There’s one thing. Next month you guys”—meaning the Stones—“are playing the Hard Rock Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. I want to go.” He said, “David, I can get you tickets, but they are expensive.” I asked, “How much?” He said, “$500.” I then said, “I’ll take two” for my ex-wife–we are since divorced. So we went to Vegas. I got to meet Charlie Watts. He and I click (talking) on jazz footage.

The next thing I know in the summer of 1998 I am in Holland backstage with the Stones, hanging out in their inner sanctum, and Charlie and Chuck introduce me to a Belgium promoter who subsequently introduced me to the (French-speaking) Belgium television station RTBF where I get the idea to start representing European libraries, and the rest is history.

The moral of the story is that life presents really bizarre opportunities at certain moments. If I had not pissed off a Spice Girl, I would not have been kicked out of the green room to the room downstairs (at Letterman), and the chain of events would not have occurred, and you and I would not be talking now.

The Reelin’ In The Yearsmusic footage archive ranges from full-length concerts to in-the-studio live and lip-sync performances as well as interviews, and B-roll footage with performers.

It’s about 30,000 hours of music footage that we represent.

Reelin’ In The Years represents the rights to music footage from over 50 television stations and independent archives throughout Europe, North America and Australia?

Yes.

The rates for use are based on per minute/per song, but not per cut. Rates also vary depending on the rights required–for television, home video, theatrical use–and for use in different territories, North America, the UK, Europe, or worldwide?

Yes. If someone just wants to show it in Canada for a year, that’s one thing but if they want all rights, all media that’s another. If they want just film festival rights, that’s something else. But yes, it does depend on use, and it’s permanent. If you are using anywhere up to a minute of Aretha Franklin doing “Respect,” it’s a certain rate. But it is also important to note that when we license a clip we are licensing the footage. We do not own the publishing. If it’s a live recording, we own the recording. If they want to use footage, people have to go and clear those other rights. That’s their responsibility.

Reelin’ In The Years Productions owns the footage only? Music (if original tracks are used), and publishing rights need to be cleared as well?

We own the footage. The copyright. When we license something, it is the end user’s responsibility to clear all of the those things, and Indemnify me and my clients. We don’t have those rights. We are very clear about that in our agreements. We are giving you the copyright of the footage. We represent “The Merv Griffin Show.” If you use Devo on “The Merv Griffin Show,” as an example. In that case, they are lip-syncing, so you are also going to have to clear the master recording with the record company which would be Warner Brothers.

Reelin’ In The Years Productions & Photo Archive represents the work of quite a few leading photographers, including Tom Gundelfinger O’Neal, Gered Mankowitz, Richard E. Aaron, and Eric Hayes as well some private archives, and has launched a photo site showcasing its music-related still images.

Yes.

With an archive of over 200 million images, Getty Images dominates the stock image sector.

They do. I am just trying to carve out a niche for myself. With my photographers, I don’t know if I am going to be successful in the print form because they (Getty) have a lock on it. We have a couple thousand images right now which is obviously not a lot compared to Getty, but we are proud of what we have.

You utilize these photos to supplement film projects?

Precisely. And we have a lot of business like that. If someone is doing a film on Dolly Parton, “Here’s 200 images of Dolly Parton.” Great and we will license stuff. I’m in the door. Why not show them (film makers) stuff? But we are not looking to be Getty with it. I’m more boutique. And I’m not looking to take on every

Did the partnership with White Horse Pictures make sense due to several factors, like sales of DVDs being practically dead coupled with continual infringement of visual music content by streaming services like YouTube, and the growing development of an ancillary music video service that has become The Coda Collection channel now launched on Amazon Prime? At the time, you both were likely seeking new business models for music-related videos and documentaries.

Yes, but I’m in a fortunate position in that licensing clips is my main business. I’ve made films in the past. But it’s been a long time. More of a hobby than anything else. So I work with film makers like Nigel and Frank and whoever that are making really quality films. That is one of the things that I really like about Nigel and his team is that they care about the story. They care about getting it right. They are not making some cookie cutter documentary that, “Oh, I feel good.” There’s meat on the bone there, sort of to speak

Significantly, filmmakers like Nigel, and Frank, and Ron Howard, and others are producing new music content.

Right, exactly.

There’s so much vintage music content out there, but if you can produce new content out of older footage, that’s vastly important.

You look at it as the canvas is already painted, but the painter–the directors and producers of the footage–puts his or her work on a canvas with the footage and the music that was made.

Then someone comes along and properly frames it through editing and presentation.

That is what Nigel does. He frames the archival footage, and the history of a band with a beautiful frame, and makes you appreciate it. I will use an analogy that when you order Japanese food, like sushi at a really nice Japanese restaurant, and the presentation on the plate is just like, “Wow,” right? It makes you feel like you have gone to a 5-star hotel or something. There is a certain way that something is presented. That is kind of the way that I look at Nigel, and other quality filmmakers. That is what they do. They really frame it right. The Bee Gees’ film is so great because to me the documentarian’s job is to do a number of things. Entertain. Inform, but also make you look at an artist like you haven’t before. I love the Bee Gees. I didn’t love the Bee Gees more by watching the documentary because I was already hooked, but there are a lot of people who have come up to me and said how much they enjoyed it.

Any future collaborations with White Horse Pictures you can talk about?

No. All I can say is that there are some really cool projects that are coming down the pike, that I am involved with, and that I am excited about. But no, nothing I can talk about.

One thing we can talk about is the recent launch of The Coda Collection helmed by CEO Jim Spinello, director/producer John McDermott, Janie Hendrix of Experience Hendrix, Yoko Ono and the Estate of John Lennon, and veteran entertainment lawyer Jonas Herbsman.

At present The Coda Collection has licensed many concerts and programs from our archive, including the American Folk Blues Festival 1962-1966 series (co-produced by John and Experience Hendrix in 2003).

In 2018, you were approached by John about The Coda Collection because of your close relationship and simply because Reelin’ In The Years Productions has such a large archive of music footage.

Well yes, John came to me two years ago. He’d got all of his ducks in a row and, and he said “Okay David, we are serious. We want to do this. I want to lean heavily on your archive because you have so many unique unseen things.” One of the things they are putting up is the concert (“Lady Soul”) with Aretha Franklin in ’68. “Lady Soul” is the name of the special produced for Swedish TV in May 1968. While it’s been on YouTube for years, they are going back to the master. I have the master because I represent the rights on behalf of SVT (Sveriges Television) which is the public broadcaster in Sweden. None of this stuff is going to be bootleg quality material.

Your relationship with John goes back to 1998.

I can’t recall what it was, but there was a DVD that had been put out in the market that had used my client’s footage with clearances, and it was Jimi Hendrix. I was trying to build a consortium to put a collective foot up their ass. I reached out to John, and he and I clicked. That issue resolved itself later. Anyway John and I really clicked. He’s amazing. I love John. I love Janie (Hendrix). A couple of years later John came to me and said, “Let’s do a Jimi Hendrix release because you’ve got some Jimi Hendrix footage. So we did our first thing together in 2001 called “Experience Jimi Hendrix,” and we released some footage from Sweden from ’67 and ’69, and that was the first time that I had done a DVD. Then I found the “American Folk Blues Festival (1962-1966)” material and went to John, and he lost his mind, “Oh my God, we have to do this. We put it out in 2003.

The first of four DVD editions of “American Folk Blues Festival” earned a Grammy Award nomination for Best Long Form Music Video.

Yes. I love that I beat out Martin Scorsese in The Blues Foundation’s the Keeping The Blues Alive award in Memphis in 2004 for “The American Folk Festival 1962 – 1966 Volumes One and Two.” He had his (7 episode) “The Blues” series. I always enjoyed the fact that I beat Scorsese at an award.

The Scorsese blues series was a big deal because it had aired on PBS.

But I think we got our Grammy nomination because of the Scorsese series. So it’s a double-edged sword, if you will.

Sony Music Entertainment is an equity partner in The Coda Collection and content partners include Warner Music’s Rhino Entertainment, Concord Music, Mercury Studios (Universal Music Group), Creem Magazine, Reelin’ In The Years Productions and others.

Where I make my money is very simple. This is one thing I love about The Coda Collection, and I really want to drive home two things. One it is unlike Spotify which utterly fucks artists over in my opinion; in terms of a model they are not artist friendly. What I like about The Coda Collection is—for years people have been coming in and saying, “Hey David we want to do this platform and stream, we will give you”… the drip drip drip, the pennies. “No fuck off. I’m not waiting for drip drip drip, pennies. No. I’d rather not do it.”

John’s model is go to people like me that own footage, pay a license fee—I’m not going to say what the license fee is other than it’s a reasonable number. It’s a three-year deal for streaming. So in three years, they can renew if they want. There are no royalties, but it doesn’t matter. It also pays the artists a license fee. It’s, “Hey, I’m going to give you X amount. We can show this for three years on this platform.”

And music publishers and other rights holders involved have to be paid.

Yes, they do. But the point is that they are paying the people that are supposed to be paid. Now about YouTube. One of the things that is very enticing about The Coda Collection is that I’m tired of seeing my stuff on YouTube. The part of the arrangement that they have with everybody (to take down content). Let’s just take the “American Folk Blues Festival” DVDs. Sadly that footage is all over YouTube and you know what?—especially during the pandemic—I don’t have time to spend all day whack-a-moling, taking this footage down as it pops up—but they are going to be able to start removing that stuff enmasse on YouTube because they (The Coda Collection) will have the algorithms to the masters that I am going to give them. So it will start to disappear at a rapid rate.

(Under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), websites like YouTube are required to follow certain steps to ensure copyrights are not infringed. When a copyright owner files a DMCA takedown request in a manual claim, YouTube is required to expeditiously remove the allegedly infringing video. However, the request must be accompanied by the copyright owner’s contact information, description of the copyrighted content they are seeking to protect, and a sworn statement that the video at issue uses copyrighted material without authority. YouTube needs only take reasonable steps to notify content creators that their video was removed.

YouTube also has a computer algorithm for filtering and blocking allegedly infringing content on its site before it becomes available to the public. When a content creator uploads a new video on YouTube, it is scanned against the Content ID database for infringing material. If there is a match, the creator will receive a Content ID claim against their video. The owner of the copyrighted material is then notified and may either block or monetize the video and collect all the advertisement revenue that the alleged infringing video generates.)

YouTube is allegedly slow on DMCA takedowns.

They have been fairly good about it with us because I had my lawyer write a legal letter that I use as my form each time. I take that letter, and I enter Schedule A which is the clip I want removed. But honestly, it is just a pain in the ass, Larry. That’s the thing.

Amazon Prime members in the U.S. have access to over 150 titles streamed on The Coda Collection for $4.99 per month. Titles offered at launch include the streaming premieres of “Music, Money, Madness…Jimi Hendrix In Maui,” “The Rolling Stones On The Air,” “Johnny Cash at San Quentin,” “Miranda Lambert: Revolution Live By Candlelight,” and the streaming premiers of Bob Dylan’s “Trouble No More,” the forthcoming authorized Dave Grohl documentary, and performances by Dead & Company as well as newly-filmed, exclusive performances by such artists as Jane’s Addiction and Stone Temple Pilots. Were you involved with the curating and licensing for The Coda Collection?

My involvement is that I know my library very very well. and John and I have known each other so long so we have a past mutual respect, and trust. I have made a lot of suggestions to John, and there were a number of things that he was trying to clear for the artists. He’s going to be drawing from my well a lot. I don’t know how many people that they expect to have on this platform signed up, but I’m going to throw a number out–and this is not from him (John) this is me spit-balling—-but look if this succeeds, look at it this way that over time and across the globe, if 10 million people sign up to this platform at $4.98 five bucks that’s generating $50 million a month.

Now, of course, that doesn’t all go into their (The Coda Collection) pocket. Amazon Prime takes its cut. But the point is with money like that, there’s a lot more money to spend on bringing content in. What I am so excited about is not just as a businessman, but I’m a music fan; It started out as a hobby ]. It’s still business but’s it’s a hobby all mixed into one. I would be jumping up and down for joy (over The Coda Collection) even if I wasn’t involved because this is going to be the kind of thing when you are in bed at night on your iPad or computer and you are bored with the news and you don’t want to watch a movie. What is on The Coda Collection?” Oh, I can watch Miles Davis? Or you dream of hip-hop, “I’m going to watch Public Enemy,” or if you are into country, “I’m going to watch Johnny Cash.”

Look, some people like one genre of music, and that’s all they like. Others like me, I listen to Frank Sinatra and the Sex Pistols, and everything in between. It depends what mood I’m in. So I like a lot of different things. The whole point of what they are trying to do is not build a platform that is just for what I consider to be the greatest music of all time. ‘60s, the Beatles, the Stones, James Brown blah blah–sure that’s my passion–but they are trying to build something so that if you are into Taylor Swift or Justin Bieber, which I am not (but I respect that people are), there will be something there for those fans as well which is a smart way to do it because you are under no obligation to watch Justin Bieber. You can watch Jimi Hendrix. You decide what you click.

Many music documentaries I read about in Billboard, Rolling Stone, Q, or Mojo are hard to find.

Yep. You are right. Another thing is that The Coda Collection’s plan isn’t just to release a concert of Bob Dylan or whatever, but it is also going to be documentaries. I do think it does have potential because YouTube has bastardized, and ruined music footage other than they don’t do original footage. Apple doesn’t either, but to have it play like this on The Coda Collection where you can go and watch your favorite artist is exciting. It’s going to take time to build up to where there is such critical mass. But they have already licensed quite a few titles from me which telling me that their numbers are very good.

In 2020, Jeff Jampol, manager of the Doors, asked you to represent their footage and photo archive for licensing. Both Doors’ members, Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek, were film students at UCLA, and their passion of film-making was evident throughout their tenure. In1968, Paul Ferrara, a friend of the band, began filming the group on 16mm; capturing snippets of the band in concert, backstage, in the studio, on vacation, and in airports Subsequently, they brought in Babe Hill to capture audio using a portable Nagra recorder, capturing The Doors at the Hollywood Bowl on July 5, 1968. Footage was edited into a film called “Feast Of Friends” that was never officially released. A restored version was released on DVD and Blu-ray in 2014.

In 2008 The Doors had all of the existing 16mm film transferred to Hi-Def. The film lab, prior to transferring the footage, spooled the original film reels onto larger reels, which caused all of the pertinent date and location information to be lost.

Not one reel, but a series of reels all out of order.

Is it true that you and your team had to figure out, using whatever visual clues were available in the footage what was on hand? Including using street signs, local advertising to identify particular cities, and even studying the tiles on the floor, and ceiling at LAX to decipher what airport they were in?

Yep. That is the honest to God truth. Working with their archivist David Dutkowski, it was very tedious. But I get really in the weeds with stuff. So I would mark down what clothes they were wearing. Everything. Then it got to the point, yes, we were looking at the tiles at certain airports, researching online images of LAX in 1968. That kind of thing. I was able to identify virtually every room that they were in. There’s no sound because the sound on that reel hadn’t been synced up yet. Imagine dumping a jig saw puzzle in the middle of a street, and you don’t have the box to know what the picture is.

Do the Doors still have quite a bit of footage?

The main thing they have is the stuff shot in ’68. There’s hours and hours of that. But it was shot on one camera with one guy recording on the Nagra. Except for the Hollywood Bowl, which was a 3 or 4 camera shoot, everything else was shot cinéma vérité style. It was meant to be a glimpse into their world. It wasn’t meant to be full songs. But it is such important footage. One of the things we found– all of a sudden it pops up, and I have to find the sound in their vault to sync it up–is 8 minutes in black and white of Howlin’ Wolf in a club in 1968. I was like, “What the heck is this?” Then Robbie told me, “Oh yeah, Jim shot that.” Mind- numbing.

Speaking of mind-numbing I will give you some information on a piece of footage I’ve found that I’ve not told anybody about yet. Being Canadian, you can be the first person to announce it. I’m not going to show it to anybody, yet. One of my clients’ parents shot this footage, and very recently he was going through his vault. Long story short, he found about 8 rolls of 16mm film in color of Joni Mitchell and Graham (Nash) from March 1969, shot in Saskatoon.

From when Joni returned home to visit her parents, Bill and Myrtle Anderson?

Exactly. It’s footage of Joni at home with her mother and father. There’s footage of her at Sears signing autographs. About half—there’s about 75 minutes of material—half of it has sound. You can’t even believe that you are seeing it because it is so intimate.

Has Joni seen it yet? She was so very close to her parents, especially her mother.

Joni is about to know about it. I have showed it to Patrick Milligan (Rhino’s Director of A&R and Mitchell’s co-producer of “Joni Mitchell Archives. Vol. 1”). He’s going to show it to Joni. I think she’s going to cry when she sees it.

Who shot it?

I can’t tell you. But it has been sitting in a vault for 52 years. What is amazing about it is that while Graham is in the shots, he was nobody then. He was an ex-member of the Hollies. “Crosby, Stills & Nash,” the first album by David Crosby, Stephen Stills, and Graham didn’t come out until May (29th). So when Graham is next to Joni, the cameraman cut Graham out of the shot. There’s a point near the end where she is being interviewed by a local Canadian reporter backstage in Saskatoon, and Graham is so rude going, “We really have to wrap this up.” Joni, who was deep in the interview, kind of gives him a look, “Like who are you?” She’s like, “No I can take a few more questions.” It was an amazing thing to see. It is really great, great footage. It is one of those things that you find that you go, “I cannot believe that not only that this exists, but I can’t believe for 52 years nobody knew about it. That is just mind-numbing.

To date, Reelin’ In The Years Productions has transferred and cataloged the archives of television personalities Brian Linehan, Sir David Frost, Merv Griffin, Rona Barrett, and San Diego entertainment reporter and TV personality Fred Saxon.

We have signed, but we haven’t got the papers yet on a Toronto person I’m sure you will remember, Dini Petty. She stored her tapes at York University, and because of COVID-19 we have been waiting to get them out to transfer them.

(“The Dini Petty Show” was a Canadian daytime television talk show, which aired on stations affiliated with the Baton Broadcasting System from 1989 to 1999. It originated from Toronto’s CFTO-TV. Petty’s contract with CTV ended in 2000, which led to a legal agreement resulting in Petty being awarded the original broadcast tapes to “The Dini Petty Show.” She donated the tapes, but not the rights, to the Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections at York University in 2010.)

I was on Dini’s show a lot, including a nostalgia-based program featuring Ray Davies of the Kinks, Don Mclean (American Pie”), Hank Ballard “(The Twist”), Jose Feliciano and Larry Evoy of Edward Bear (“Last Song”).

You were all on the same show?

Oh yeah. Dini got Ray Davies to talk more freely than anybody else I can remember.

Oh, I need that episode. Thank you. I need to get that one.

Dini is fascinating to watch.

I have been watching a few clips. It (the archive transfer) was supposed to happen and the COVID hit and York University shut down. We are just waiting now for them to open up and to send the tapes down here to digitize them.

Reelin’ In The Years has represented The Brian Linehan Collection since 2015.

Yes.

Until his death in 2004, Brian was Canada’s leading entertainment TV personality. He set a standard for celebrity interviewing and reporting through years of meticulous research that few have matched. He hosted “City Lights” (1973-1988) and “Linehan” (1996-1998).

(When Brian Linehan died, in 2004 from non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, he left behind an estate totaling $4.5 million, including three decades worth of research material, correspondence, photographs and recordings, to the Toronto International Film Festival Group’s reference library. The Brian Linehan Charitable Foundation was established from the proceeds of the estate.)

You made that deal with Brian’s long-time advocate, adviser and friend, Toronto lawyer Michael Levine?

Michael is a very dear friend. I love Michael. I will tell you this I love Michael, but I am always glad to be on his team because Michael is the kind of guy who does not take any bullshit. We are cool. I love him.

You received over 2,000 tapes that had been sitting in a storage facility north of Toronto, and were in danger of being destroyed. You spent 5 weeks transferring and cataloging over 1,300 of the tapes on many different formats, from 2-Inch quad to 1-inch, Betacam and Umatic, You were able to transfer all the material in your office with the exception of the 2-Inch quad tapes, which needed to be handled by David Crosthwait at DC Video.

Oh, it was unbelievable what I had to go through. I probably got 2,000 hours of it and it was scattered everywhere.

Besides having an authoritative knowledge, Brian spoke in interviews with an intimacy usually reserved for close friends. This was superbly captured on SCTV with Martin Short as probing interviewer Brock Linahan.

Of course, yes yes yes.

Almost certainly, without your involvement, footage from the likes Brian Linehan, Sir David Frost, Merv Griffin, and Dini Petty would be lost or destroyed and forgotten.

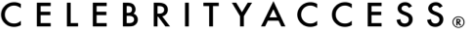

The thing is that I love what I do. I am really passionate, as you probably have figured out. But I really feel that in some ways, besides the business for myself and my clients, that I am doing a service to history. You take “The Dini Petty Show” as an example. It is just sitting in a vault in York University doing nothing. By signing a deal with her, and then investing money and time, and having the chance to offer it up to the film-making community, just like Merv, and David Frost, and the music stuff, I do feel that I am doing something that is important. I don’t say that in an egotistical way. I just say it about anyone doing this kind of work. Not just me. I think that this is just so important. One of things that I’ve thought about a lot recently is how important footage is. That can be anything from the Beatles on “The Ed Sullivan Show “because that was a monumental thing.

Deterioration is a ticking clock with footage. If left, footage is just going to deteriorate, and it’s going to become unplayable. You digitalized over 2,000-plus hours of footage for the 2014 release of the 12-DVD box set, “The Merv Griffin Show – 1962-1986.”

(During his show’s decades-long run, Merv Griffin filmed approximately 4,855 episodes with an estimated 25,000 guests. More than half of those episodes are missing; destroyed or taped over, a common practice in the for decades in television

The box set of 44 episodes features interviews and performances with over 200 guests from entertainment, politics, music, sports, fashion, literature and art, including performances by Aretha Franklin, the Everly Brothers, Isaac Hayes, Merle Haggard, Carole King, Stevie Wonder, and a 19-year-old Whitney Houston making her network TV debut in 1983. There’s also a mind-boggling 1965 interview with music producer Phil Spector.)

I have really come to think, especially in the past year, of just how important footage is, and how the documentation of things are. It can be something as entertaining as the Beatles on Ed Sullivan. Now I was born in ’66, those of us that can relive that moment in time, and pivotal time in music, can view that. Then you have something far more serious like George Floyd being murdered, and the people who shot all of the footage.

(On May 25, 2020 Minneapolis police officers arrested George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man, after a convenience store employee called 911 and told the police that Floyd had bought cigarettes with a counterfeit $20 bill. Seventeen minutes after the first squad car arrived at the scene, Floyd was unconscious, and pinned beneath three police officers, showing no signs of life.

By combining videos from bystanders and security cameras, reviewing official documents, and consulting experts, The New York Times reconstructed in detail the minutes leading to George Floyd’s death. its video shows officers taking a series of actions that violated the policies of the Minneapolis Police Department and turned fatal, leaving George Floyd unable to breathe, even as he and onlookers called out for help.)

Or on the street during the riots, and the U.S. Capitol resurrection. These are images that are important to history. Purporting to tell a story. Stories that are fun. Stories that hard. Stories that are sad. And you think about this and how would we view the Kennedy assignation if Zapuder had not shot that footage.

(The infamous Zapruder film is a silent 8mm color motion picture sequence shot by Abraham Zapruder with a Bell & Howell home-movie camera as President John F. Kennedy’s motorcade passed through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas, on November 22nd, 1963. Unexpectedly, it captured Kennedy’s assassination.)

Britain’s Dave Clark held back the Dave Clark Five recordings for years. After the band called it quits in 1970, releases were quite sparse. In 1993, Clark finally supervised the 2-CD, 50-track release, “The History of The Dark Clark Five” with Hollywood Records. There’s now “All the Hits” (BMG), available standard in CD and LP editions with 16 tracks, while the deluxe editions have 28 tracks each.

In the 1980s, Dave Clark acquired the rights to the 1960s UK music show “Ready Steady Go!” and bought the rights to the surviving recordings.

In 2018, BMG Rights Management announced that it had acquired the ancillary rights to ”Ready, Steady, Go!” BMG Books has since published Ready Steady Go!: The Weekend Starts Here,” a lavishly illustrated history of the show.

Are there other rights holders hoarding content?

In his case, he was hoarding it.

Have the “Ready Steady Go!” shows been commercially released?

No. But I think that he sold the rights to BMG. I don’t believe they paid a lot of money for it. I wouldn’t have paid a lot of money either for it for a very simple reason. Not all, but a lot of “Ready Steady Go!” is lip-synced. You need the labels to do anything with it. If any part of it is the record, all of it is the record. “The Ed Sullivan Show “did that a lot to. The Stones, when they did “Let’s Spend Some Time Together”—substituted for “Let’s Spend the Night Together”–the backing track was the record. It isn’t truly a live performance. Mick and Keith were singing over the top of the backing track. Most of the Motown stuff was live on Sullivan.

Footage from mid-‘60s American music shows are hit and miss. Like ABC-TV “Shindig!” footage you can find, but not much from NBC-TV;’s “Hullabaloo.”

Not anymore. The sad thing is that only 4 color shows exist in kinescope of “Hullaballoo,” the rest are really bad kinescopes. They were done really poorly.

From growing up in Plainview, New York, near the North Shore of Long Island, your older brother Lawrence used to tell you that two doors from your house at 20 Elaine Place that Steely Dan—then Donald Fagen, Denny Dias, and the late Walter Becker–would rehearse in a garage at the home of Debbie Bagica who dating Denny Dias. You were about 4-years-old then so you wouldn’t know. In 2001, during rehearsals for the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame Induction ceremonies at which Steely Dan were being inducted, you asked Walter about the story.

And Walter goes, “Oh yeah, I remember Debbie Bagica.” Denny Dias was from one town over which was Hicksville. My brother also tells the story, and I don’t know if it’s true, that my dad called the cops on the band. My dad died of a heart attack in 1970 so I don’t know. It’s possible that a band was rehearsing there.

What did you mom and dad do?

My dad was in advertising, but he died suddenly of a heart attack in 1970. My mother didn’t work until she moved us (brother Lawrence, and sister Lisa) to San Diego in 1977. She was a medical transcriber. She listened to recordings of doctors’ notes about patients, and transcribed them for their medical records.

Larry LeBlanc is widely recognized as one of the leading music industry journalists in the world. Before joining CelebrityAccess in 2008 as senior editor, he was the Canadian bureau chief of Billboard from 1991-2007 and Canadian editor of Record World from 1970-80. He was also a co-founder of the late Canadian music trade, The Record.

He has been quoted on music industry issues in hundreds of publications including Time, Forbes, and the London Times. He is a co-author of the book “Music From Far And Wide,” and a Lifetime Member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame.