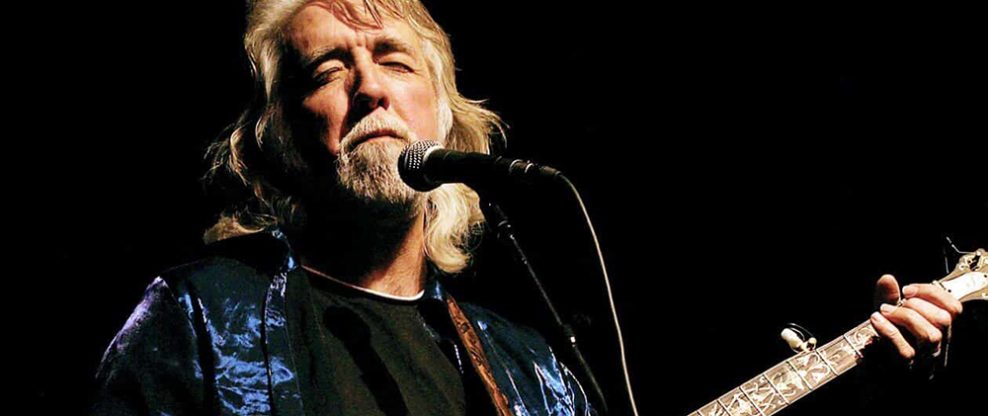

This week In the Hot Seat with Larry LeBlanc: John McEuen, multi-instrumentalist, producer, and author.

One of the most prodigally talented musicians in American history, John McEuen was a member of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band for a half-century before departing at the end of its 50th-anniversary tour in 2017, the same year he was inducted into the American Banjo Museum Hall of Fame.

During his extraordinarily restless and fruitful life, multi-instrumentalist (banjo, guitar, mandolin, fiddle, dobro, piano, dulcimer) McEuen who is currently living in Franklin, Tennessee, has at last count performed over 10,000 live shows and completed over 300 television shows— with the Dirt Band, solo and with others–as well as produced a handful of formidable film documentaries.

While the Dirt Band’s catalog bursts with stellar music, their landmark 1972 album, “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” was the one that cemented their reputation as performers who pushed musical boundaries.

Skillfully executed, “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” contains some of the frankest, most appealing, and least guarded performances in recording history.

In reading McEuen’s lavish 225-page new book “Will The Circle Be Unbroken: The Making of a Landmark Album” is to be whisked back in time to August 1971 when a group of musicians, amid the sticky late-summer Tennessee heat, spent six days circled together in the old Woodland Studios building on a corner street in East Nashville, where they merged genres, and generations, recording bluegrass and old-timey country tracks.

McEuen’s book is chock-full of photos taken by his brother William E. “Bill” McEuen who produced the Dirt Band and the album, and the book shares behind-the-scenes stories of the sessions, capturing the players in conversation, with additional reminisces by McEuen and with members of the Dirt Band, as well as Gary Scruggs, Marty Stuart, and numerous contributors.

Those long-haired California boys paired with bluegrass and country legends of the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, such as Mother Maybelle Carter, Roy Acuff, Earl Scruggs, his sons Randy and Gary, Doc Watson, Merle Travis, Jimmy Martin, Bashful Brother Oswald, Roy Huskey, Norman Blake, and Vassar Clements, resulted in a 38-song triple recording that constituted the first such integral collection of its kind, and is regarded as a milestone in American music.

There are young people in the music business, not to mention America at large, who have hardly heard of “Will The Circle Be Unbroken,” and who cannot know what it represented to American music at the time of its release.

It not only turned heads within the music industry, particularly in staid Nashville but, along with then countrified releases by Bob Dylan, the Byrds, Ian & Sylvia, the Flying Burrito Brothers, Gram Parsons, Emmylou Harris, Linda Ronstadt, Waylon Jennings, and Willie Nelson, it laid the foundation of Americana music that evolved as a recognized source of popular culture.

The future Renaissance man of American music was born in Oakland, California, and moved to Orange County outside of Los Angeles with his family during his high school years.

He began playing the banjo at age 17, after hearing live bluegrass at a club near his home.

Growing up in California in the ‘50s and ‘60s meant that great American bluegrass and blues musicians were only evidenced on records and radio, making it hard to catch a glimpse of the artists behind the sound. But McEuen had a proficiency for picking notes off records, and he quickly found success with the banjo in the Los Angeles area, winning Southern California’s annual Topanga Banjo Fiddle Contest and Folk Festival.

His performances with the Dirt Band over five decades before he stepped off the bus in 2017 — he previously took a hiatus from 1986-2001 but had been performing full-time with them since his return — are universally considered to be of the highest quality.

As Garth Brooks recalled in 2014, “I went to see Nitty Gritty Dirt Band in college at Gallagher Arena (at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater, Oklahoma). A bunch of guys in the dorm pooled our monies together and threw in an extra buck a piece to pay one of the guys to sleep out for tickets. We got front row. We were having the time of our lives when during a fiddle solo, John McEuen leaped over the monitors and past the edge of the stage and landed in between John Mathiason and me. McEuen never missed a lick of that solo. THAT MOMENT is forever etched in my soul.”

With his mastery of multiple instruments, and retaining his ties with Nashville and his Los Angles friends, McEuen became a sought-after sideman as he steadily grew as an interpreter, and as a technician.

He brought depth and richness far more than a supporting player to performances by such luminaries as Steve Martin, Michael Martin Murphey, the Allman Brothers, Phish and others.

Since leaving the Dirt Band, McEuen has hardly curtailed his activities. Far from slowing down as age encroaches—he’s now 77—he seems to be to accelerating by playing with the Circle Band, his ensemble of string-players including former Dirt Band co-founder Les Thompson.

In concert McKuen proudly plays a Deering John McEuen Signature Model banjo with its unique 24 Karat gold look, trimmed in ivoroid, and coral snake decorative edge inlaid purfling, accented with premium engraving on the tone ring, armrest, and tailpiece.

To witness a John McEuen performance is to be struck by the notion that he’s one of the finest entertainers you’ve ever heard. Someone who has touched a generation of listeners and, perhaps more than anything else, as shown with the timelessness of “Will The Circle Be Unbroken,” that this music still holds up in wondrous ways.

And, believe him, “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” will live forever.

Much of your life was chronicled in your 2018 book “The Life I’ve Picked.” That said, you really need to sit down with a documentary film unit and drill down on the era you have lived and worked in, as we keep losing so many unique voices of our music culture.

Well, I am in five museums. The Western Edge Exhibit: The Roots and Reverberations of Los Angeles Country-Rock at the Country Music Hall of Fame is a real good deal. It will be up for three years, and it honors the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band as part of the L.A. country-rock thing. There are a couple of 8×12 foot photos of the Dirt Band on several of the walls and an exhibit. It has other people like Herb Pedersen who was greatly influential, and there is some of the work of Chris Hillman. He is the reason I got a band. I was going to college and “Turn! Turn! Turn!” came on the radio. It was the greatest thing that I had ever heard. I pulled over and waited for it to come on again. I didn’t go to school that day. I knew that Chris Hillman had been in the San Diego-based bluegrass group, the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers (with Bernie Leadon), and he was playing bass in the Byrds. I said to myself, “If he can do it, anyone can.”

Have you really released 46 albums, including 7 solo recordings?

A couple of them might be compilations. A “best of” package or something. With the Dirt Band, it’s 35 or 36 albums, and then I’ve done 9 or 10 of my own. By my own, I mean albums that I have produced, played on, or didn’t play on, but produced. Like Steve Martin’s album (“The Crow: New Songs for the 5-String Banjo”). I produced that and played on it. We won a Grammy (in 2010 for Best Bluegrass Album).

Originally released in November 1972, as a three-LP set, and three-cassette tapes, “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band was remastered and re-released in 2002 as a two-CD set. The original album was certified platinum by the RIAA in 1997, indicating shipments of 500,000 copies.

While none of the celebrated country-oriented albums by people like Bob Dylan or the Byrds made a significant dent in the country music world, the “Circle” album went to #4 on the Billboard Country Album chart.

Popularity brought honors far beyond the usual.

Rolling Stone called the “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” recording, “The most important record to come out of Nashville” and the album was named by Country Music Television (CMT) as one of the 40 most important albums in country music. The recording was inducted as a historic recording into the Library of Congress in 2004, and the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2012.

“Will The Circle Be Unbroken” still sells heavily as a catalog release.

That is so cool.

When Nitty Gritty Dirt Band co-founder Jeff Hanna was asked to write on “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” for your book “Will The Circle Be Unbroken: The Making of a Landmark Album,” he wrote that, “It seemed a daunting task.”

He’s right.

The recording represents a confluence of two eras of country music history that directly inspired the Americana roots music genre.

It isn’t just that the album is now 50 years old, and was the ultimate picking session of the Dirt Band members with their bluegrass heroes, but it’s also part of a lot of people’s DNA, a culturally conscious recording that has taken on a life of it own

The only album that affects me in the same way is “Music from Big Pink,” the 1968 debut studio album by the Band.

Yeah, it is very interesting with this book that I wrote. I had to talk to people, and get some impressions, and it‘s like “Chicken Soup for the Soul” (1993) with “Will The Circle Be Unbroken.” This album affected people more than just a record, and that is quite an honor. I am really glad that it works.

Both “Will The Circle Be Unbroken,” and “Music from Big Pink” appealed to rock audiences who came to country music via the Byrds, Bob Dylan, the Grateful Dead, the Dillards, New Riders Of The Purple Sage, Marty Robbins, Linda Ronstadt, and Jerry Jeff Walker, only to discover Ray Acuff, Doc Watson, Earl Scruggs Bill Monroe, the Country Gentlemen, J. D. Crowe’s New South, Tony Rice, David Grisman, David Bromberg, John Hartford, and Ricky Skaggs who each benefited from the musical match-up and went on to tour to new audiences as traditionalism appealed to urban folk music fans in the 1960s.

While bluegrass, pushed aside by more modern country music and by rock and roll, was hard to find on commercial radio, it spread at a grassroots level.

And joining labels like 4 Star, Goldband, Rebel, Columbia, Vanguard, Folkways, Arhoolie, Okeh, Bluebird, and RCA in releasing traditional country music, and bluegrass in the ‘70s were Flying Fish Records, Rounder Records, Takoma Records, and Sugar Hill Records.

As Brett Milano wrote in Udiscovermusic (August 1, 2022) “The worlds of country and rock music were coming together by the early 70s. The Byrds had done ‘Sweetheart Of The Rodeo’; Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash had recorded together; Linda Ronstadt’s solo career was underway; the Grateful Dead had done Merle Haggard and Marty Robbins songs; and Willie Nelson was off inventing outlaw country. Yet bluegrass wasn’t really part of the equation – that was a previous generation’s sound. The young folks may have had some Doc Watson and Roy Acuff records in their collections, but few were covering those songs, and nobody was daring to invite those legends into the studio.”

“Will The Circle Be Unbroken” was originally released by United Artist Records.

Catalog number UA 9801.

In 1969, United Artists Records merged with co-owned Liberty Records and its subsidiary, Imperial Records. In 1971, Liberty/UA Records dropped the Liberty name in favor of United Artists.

That deal was made at 6920 Sunset Boulevard in 1971 in ‘the Liberty building, directly across from Hollywood High. My brother Bill and I met with Mike Stewart, the president of the label. We celebrated across the street at IHOP. I had French toast.

What budget did Mike Stewart give you?

He put up $22,000 for the album.

Were you able to do it for that budget?

We did, and one of the reasons was that two-track really worked out. If it had been 16-track, a reel of 16-track tape then was $180.00, and we would have used about 30 of them, and that would have depleted our budget. But two-track tape was only about $35.00.

Mike Stewart, while an L.A. company man, deserves credit for running the most distinguished show in town. He went on to serve as VP of United Artists Pictures for more than a decade. He supervised the film soundtracks of “A Hard Day’s Night,” “Rocky,” and various James Bond film scores. After United Artists Pictures, he joined with the West German firm Bertelsmann to form the Interworld Music Group, and was later the president of CBS Music Publishing.

He also served as a consultant to the MCA Music Division. He was a big guy in music publishing. Big, well-known guy. I called him when I was remastering “Circle” for the CD, and he said, “John, I have three albums on my wall in my office that I helped make happen. I made 500 albums happen, but I’ve got three. I’ve got John Lennon’s first album, ‘Imagine,’ and I’ve got Tina Turner’s first album, ‘Tina Turns the Country On!,’ and I’ve got the ‘Circle’ album.”

That was really a wonderful testament to the fact that he put up the money. But he had also said, “I don’t think I will sell 10 of these.” But my brother Bill and I did the pitch for the album to him, and he said, “You guys are so passionate about this, that I’ve got to listen.” We (the Dirt Band) had just had three hit singles. That gave us somewhat of an edge.

The Dirt Band broke through with its 4th album, “Uncle Charlie & His Dog Teddy,” which reached #66 on the Billboard 200 album chart in 1970. Three singles charted: “Mr. Bonjangles” reached #9 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1971. “House at Pooh Corner” reached #53 and “Some Of Shelly’s Blues” reached #64.

With this breakthrough success, the Dirt Band was allowed to record a three-album set at a time few acts were allowed to. That came later with Yes with “Yessongs” (1973), Neil Young’s “Decade” (1977), Stevie Wonder’s “Looking Back – Anthology” (1977), the Band’s “The Last Waltz” (1978), Rush’s “Archives” (1978), and the Clash’s “Sandinista!” (1980).

The Dirt Band was initially signed by Liberty Records which was the same label as the Chipmunks, Julie London, Eddie Cochran, Jackie DeShannon, Vikki Carr, Jan and Dean, Johnny Burnette, Gene McDaniels, Del Shannon, Gary Lewis and the Playboys, and home to producer Snuff Garrett’s easy listening album series, “The 50 Guitars of Tommy Garrett.”

The Chipmunks made Liberty Records. Chipmunk Alvin was named after Al Bennett who was president of the label at the time.

Singer/songwriter Ross Bagdasarian, aka David Seville, had a #1 hit on the Billboard Top 100 with his novelty song “Witch Doctor” in 1958, selling 1.4 million units in the United States, and saving Liberty Records from near-bankruptcy.

The Chipmunks, Alvin, Simon, and Theodore were named after Liberty Records executives Alvin Bennett, Simon Waronker, and Theodore Keep, beginning with “The Chipmunk Song (Christmas Don’t Be Late)” which reached #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, selling 4.5 million copies.

Did you know Lenny Warnoker when he worked at Liberty in the A&R and promotion departments, first as a gofer and then at its publishing affiliate Metric Music? Before Mo Ostin scooped him up to be a junior A&R executive for Reprise and Warner. In 1970, Lenny became head of A&R, and then president in 1982.

We ran into him when he was with Warner Bros. My brother Bill worked with Lenny and Mo Ostin. He took Steve Martin to them, and another group. The other group didn’t work out, but Steve did. Bill managed Steve and produced his first 5 movies. He first made a record deal with Liberty Records with Artie Mogull, and then a couple of weeks later, he gave the money back because he got the deal at Warner Bros.

Who holds the masters to the original “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” album?

Well, I have them in the next room. I stole the masters from the company in 1976 when they put out an album that used some of the tracks for a compilation record. Let’s say I took the masters. I didn’t give them back. When I was remastering, the lady at the company in charge of production making the records, she closed the door to her office, and said, “John, why do you have those masters?” I said, “Betsy can you give me the artwork for this album.” She replied, “Well no. We lost it.” And I said, “I think you just answered why I still have these masters. I’m not going to lose them.” She then said, “Well okay. You send me the finished CD.” Anyway, they don’t need the masters. They have it digitally now. It sounds better than the original because the processes are better.

Why didn’t you write and publish “Will The Circle Be Unbroken: The Making of a Landmark Album” 20 years ago?

It would have been 20 years early. The 50th year came. It would have been the year 30. In the year 30 (2002) I reissued the album (as a two-CD set). I had the masters in my possession, and I remastered them for the CD and put four new cuts—two talking cuts, and two music cuts—on it.

The airing of Ken Burns’ 8-part, 16-hour PBS documentary series “Country Music” in 2019 increased attention on the album. You were featured in four episodes including one titled “Will the Circle Be Unbroken (1968-1972)” which you closed.

So the Dirt Band was recognized as an important part of history.

It gave the album a shot in the arm. Ever since the Ken Burns’ show, the “Circle” album has been in the Top 20 or 30 of three different Amazon charts. That’s been for three years now. It became obvious that I was going to have to do this 50th-year book, and in the middle of doing the book, my brother died (on Sept. 24, 2020). I wish he had lived to see the finished thing. He would have loved it, I think.

The text and the photos in “Will The Circle Be Unbroken: The Making of a Landmark Album,” stir up so many memories for me. The original album plays in my head as I go through the book.

That’s good. I wanted to answer all of the questions that I could that I have been asked over the years and add in some stories that I never got time to tell, and then talk a bit of how the record was made. And I tell a bit about how the cover was made. The meticulous effort that my brother put in to making that magic cover that the record company did not want to make. “Well, I will erase the tape then.”

Other than the musical quality of the sessions, one of the major strengths of the “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” album is its sequencing. I understand that Bill worked on that in Aspen, Colorado for five months after the recording sessions.

Yes, and to start off a three-record set with a mistake took a lot of nerve. (The lead-off track) “Grand Ole Opry Song” starts off “dat dun don.” Jimmy Martin said, “Earl (Scruggs) never did do that.” Yeah, I know. It really caught people off guard.

The effect of the informality was that it is like listening to a late-night picking session among friends.

That’s one of the things that I wanted to accomplish with my brother when we put the “Circle” album together. It wasn’t called the “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” album. That came up when Bill was editing and sequencing it, and it became obvious that was going to be the title. That’s the song.

Bill took photographs during the early years of the Dirt Band and photographed their recording sessions. Putting together the “Circle” book with 145 photos by Bill, 30 photos from the early Dirt Band leading up to the “Circle” album, must have been an emotional experience for you with him passing away in 2020.

It was a difficult process. I quit working on it for a few months because….anyway. Then I went, “Well I have to finish it. The 50th year is coming up. And there’s a story behind every photograph, including the early Dirt Band photographs that he took. They are in there. They are interesting.

Nevertheless, these wonderful photographs provide vivid recollections of both the original sessions in Nashville, and of so many people who have since passed on including: Doc Watson, Mother Maybelle Carter, Vasser Clements, Roy Acuff, Merle Travis, Jimmy Martin, Roy Huskey, Bashful Brother Oswald, as well as Earl, Randy, Gary, and Louise Scruggs.

Of course, the album was so tied to Bill.

I was tied to Bill too.

I was working on the book, and he gave me the pictures, 10 years earlier. He said, “Here, these are yours.” He gave me the pictures, and I have used them in my stage show. Where I do a video projection of all of the “Circle” album pictures, and some of the early Dirt Band.

Your shows with the Circle Band that include guitarist Les Thompson, a co-founder of band, feature Bill’s photos behind you on the screen as you play in front of it.

Yes. I also have some of the early Dirt Band on 8mm film, and video.

I spend 20 minutes on the early Dirt Band story leading up to “Circle” album, and then use all of the photos that I can to tell the story of the “Circle” album. People have just been loving it. It is a special kind of show. It is usually and hour and 40 minutes long. Not all of it is with video, but a lot of it is.

What reactions have you had?

I hear from people, “It definitely took me back. I have the original album. I bought it,” they say, 50, 40, 30, 20, 10 years ago.”

Nothing beats playing a great show and talking backstage with band members saying, “Well, that was hot.”

Well, the sound is better today. The lights are better. The venues are better in general. Well, 90% of the time anyway. And it’s fun to go and play.

Mostly you have a pre-won audience after decades playing everywhere. Those coming to see you almost certainly know your history, and they know what they are going to likely get, and even what the quality will be.

And they bring the other half of the audience that I play to. Half the people that go to a concert, I believe, don’t know what the act is. They are going to see someone and were brought by the other half. “If you go and see Barry Manilow with me, I will go and see the Grateful Dead Reunion with you.” That kind of thing happens a lot. Except for major names it’s, “We haven’t heard the music.” It’s a fun, exciting challenge to go out in front of an audience, and make them laugh, make them clap, and have them stand up at the end and not leave. That’s my challenge.

When you were 19, you and your brother Bill were delivering diesel products for your father’s business in Nashville. After going to four places to drop stuff, you tried to get tickets to see Earl Scruggs perform at the Grand Ole Opry at the Ryman Auditorium, but the show was sold out.

I had always wanted to meet two artists. Mother Maybelle Carter, and Earl Scruggs. Bill and I traveled to Nashville in the hope of seeing them both perform.

On the west side of the Ryman, people would line up to peek through the windows which were open. When it was your turn, Earl Scruggs was introducing Mother Maybelle Carter. You and Bill watched her, Earl Scruggs, and Lester Flatt perform “ Wildwood Flower” which the Carter Family had first recorded in 1928.

Maybelle and Earl lived up to your expectations?

I almost passed out. They did “Wildwood Flower,” and they followed with some quick banjo instrumental, and the place just went nuts. It was a magic moment. And I just said, “Someday, I hope to meet that guy.”

It came to pass that you did indeed meet Earl Scruggs. How did that come about?

The Dirt Band was playing its first Nashville job in late Fall of 1970. And (Earl’s son) Gary Scruggs heard that we were coming to town, and he played his dad our album “Uncle Charlie & His Dog Teddy” which had an Earl Scruggs song on it, “Randy Lynn Rag,” and (the hit song) “Mr. Bojangles.” And it had Michael Nesmith’s “Some of Shelly’s Blues” (recorded by Linda Ronstadt and the Stone Poneys in 1968) which started with a banjo.

Another song on the album was “Clinch Mountain Backstep” (penned by Ralph Stanley). I didn’t know that Doc Watson was from the Clinch Mountains. We knew very little about Doc Watson, Maybelle Carter, or the Stanley Brothers, you didn’t know who the musicians were. There weren’t credits on the albums.

Perhaps more than any other tunes on “Uncle Charlie and His Dog Teddy,” the Dirt Band’s versions of the Stanley Brothers’ “Clinch Mountain Backstep” and “Randy Lynn Rag” may have established their right to be in the same studio with bluegrass legends. “Randy Lynn Rag” is from Flatt & Scruggs’ 1957 Columbia Records album “Foggy Mountain Jamboree.”

When Gary played Earl, “Randy Lynn Rag,” he said, “I want to meet that boy.” And me being a banjo player, and being that boy, I was really pleased. When I asked Earl a couple of months later when he came to see us play Vanderbilt University, “Earl why did you come to see this band? I really appreciate it.” He said, “I wanted to meet the boy who plays ‘Randy Lynn Rag’ the way I intended it.” And that just blew me away.

You approached Earl about recording with the Dirt Band at the old Tulagi tavern and performing venue in Boulder, Colorado. You knew Earl was going to be playing Tulagi so you went, and I asked him if he would record with the band for what would become “Will The Circle Be Unbroken.”

And Earl said yes.

Yes, I met Earl first, and then 6 months later at Tulagi, I asked him if he would record with us. We had become phone friends.

You had a similar telephone conversation with Doc Watson from Tulagi a couple of weeks later.

I hadn’t met Doc yet. His son Merle introduced us that night, and I told him we were making an album with Earl Scruggs and wanted him to pick with us. He lit up with that comment, and I put him on the phone with my brother Bill, in L.A.

Chuck Morris, who was managing Tulagi’s then, provided a phone which in ‘those days’ was not easy, as he had to get about 75 feet of cord for a phone from his office downstairs. Bill knew a lot about ‘old music’ and got along fine with Doc. We were on the way.

After graduating from high school at 16, Chuck Morris earned a college degree in political science from Queen’s College (The City University of New York). Then he moved to Boulder to pursue a doctorate in political science at the University of Colorado. However, at 20, he dropped out of the PhD program, and was soon managing and booking bands at The Sink, a local club owned by Herbie Kauvar.

Morris then operated Tulagi for 2 1/2 years, hiring such notables as the Doobie Brothers, Bonnie Raitt, the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, ZZ Top, and others early in their careers.

Boulder was becoming a real musical center in the early ‘70e. People like Joe Walsh, Stephen Stills, and Chris Hillman moved there and (producer) James William Guercio opened the Caribou Ranch studio in 1972 near Nederland, Colorado, some 17 miles west of Boulder.

Eight weeks later you started recording. Six days later everything was done.

A full 40 songs were recorded.

Recording took place at Glenn Snoddy’s Woodland Studio in East Nashville which was not on Music Row. But that didn’t matter. Country artists came to Woodland because its sound was so good. By 1971, Snoddy was using tape recorders with one, two, four, eight, and 16 tracks before he upgraded a few years later to two 24-track Studer recorders.

For the “Circle” album tape ran continuously throughout the entire week-long recording sessions, including capturing the dialogue between the players. Many of the tracks—including the lead-off—begin with the musicians discussing how to perform the song.

While there were a couple of songs that were recorded two times, most of them were first takes — “no fixes, no overdubs.”

It was a good studio. It had good equipment. The engineer Dino Lappas, which my brother brought from L.A., had worked on a lot of albums from the Jazz Crusaders to the Ventures to the Dillards, and Tut Taylor and Glen Campbell albums for World Pacific. Dino was a magic ingredient to things sounding right. Get the right mics on the right instruments. And it was a wonderful thing.

Dino Lappas had a 25-year career in the recording industry as a director of recording, and chief engineer for United Artists Records, and Capitol Records in Los Angeles. He was a first-call recording engineer for live performances and did studio sessions with the likes of Don McLean, Paul Anka, Electric Light Orchestra, and War. He did the soundtracks for numerous James Bond films, the “Fiddler on the Roof” film, and the music for the original “Rocky” film. After his tenure in the recording industry, he spent 25 years as co-owner with his brother-in-law, Peter Tripodes, of Gus’s Barbecue in South Pasadena, California.

In reading your book I learned that the late Tut Taylor, a musician’s musician who played banjo, mandolin, and dobro—and who had played with the Dixie Gentlemen, and in John Hartford’s Aereo-Plain band, bowed out of the “Circle” sessions.

It didn’t work out, and we were fortunate in that because of Norman Blake, I think he filled the shoes better.

Norman also was a member of Aero-Plain with John Hartford, Tut Taylor, as well as with fiddler Vassar Clements, and guitarist Randy Scruggs, who both played on the “Circle” album.

Merle Travis, a guitar stylist of monumental influence, tricked you and Bill into believing that he was over the hill when he first played “Cannonball Rag” in rehearsals.

Oh, he was messing it up on purpose. “I want to do the ‘Cannon Ball Rag,” and he stumbled through a version of it, and we were all standing there sweating. We were at his house to rehearse for the day. Anyway, he just looked up at one point, and said, “No, I will do it like this,” and he played it perfect. Then we went in and recorded it a week later.

A unique stylist, Merle Travis had the instrumental style “Travis picking” named after him. Two years after the “Circle” sessions Merle recorded with Chet Atkins for the 1974 album “Atkins-Travis Traveling Show” which won a Grammy for Best Country Instrumental Performance.

I interviewed Doc Watson when (his son) Merle was still alive. Of course, he was known for his fingerstyle and flatpicking skills. Doc’s earliest musical influences were country roots musicians, and groups such as the Carter Family, and Jimmie Rodgers. He told me he first played in rock and roll bands.

Well, he had to make money. He couldn’t make money playing that mountain music out there. Here’s a guy that I was told was related to Tom Dooley—aka Tom Dula (whose name in the local dialect was pronounced “Dooley”) who supposedly killed Laura Foster in 1866, in North Carolina for giving him syphilis– but he couldn’t find an audience to sing about him. But he had to find work. He wasn’t yet the Doc Watson, although he was the Doc Watson. He was just a band member, and he made it (music) to survive.

In the 1860s, when the Tom Dooley story takes place, Doc Watson’s great-grandparents were neighbors of Tom Dulas’ family, and his grandparents, knew Tom’s parents. A local poet Thomas Land wrote a song about the tragedy, titled “Tom Dooley,” shortly after Dula was hanged. Grannie Lottie Watson sang the ballad in much the same version that Doc later sang it. The version of “Tom Dooley” popularized by The Kingston Trio in 1958 was based on a version sung by Frank Proffitt who lived down the road from Doc Watson.

Growing up, how did you and Bill find out about these bluegrass greats? You rarely heard bluegrass on the radio other than the Grand Ole Opry radio show or on country music shows on local television in southern California such as “Town Hall Party,” “The Spade Cooley Show.” and “Cal’s Corral.”

Or did you see these bluegrass greats when they ventured out to California?

Maybelle Carter’s music was featured on the Flatt & Scruggs album “Sons of The Famous Carter Family” recorded in 1963. She played on one cut, and that made me introduce myself to her songs, and to her musicians. Then I found one of her albums from the Carter Family on Folkways or Smithsonian. Then Bill and I played clubs around Southern California well before the Dirt Band. About one-third of our music was Jimmy Martin music.

One of the all-time great bluegrass singers on the “Circle” album, Jimmy Martin was Bill Monroe’s lead singer in the Bluegrass Boys in the early 50s. He later tinkered with the traditional bluegrass sound on his solo recordings to make them sound fuller.

Oh yeah, it was “You Don’t Know My Mind and “Guitar Picking President,” All kinds of cool songs. Jimmy Martin had them all.

As the self-proclaimed “King of Bluegrass,” and the man who created hits like “Sophronie,” “Hit Parade of Love,” and “Widow Maker,” Jimmy was never invited to be a member of the Grand Ole Opry because his reputation for wildness scared off Opry executives who were afraid of what he might do or what he might say.

That reminds me that when we did “I Saw The Light” Jimmy Martin came up to me and said, “I’m going to sing this so much like Roy Acuff, you won’t be able to tell us apart.” He did it, and I can’t tell them apart. He just really sounds like him.

I first became aware of bluegrass and blues history with Jim Rooney’s remarkable 1971 book, “Bossmen: Bill Monroe and Muddy Waters.” One half of the book, front to back, was about Bill Monroe, who helped lay the foundation of country music as the universally recognized father of bluegrass; the other half, back to front, was about Muddy Waters, the greatest contemporary exponent of the influential Mississippi Delta blues style, who played a key role in the development of electric blues.

Jim Rooney served as director and talent coordinator for the Newport Folk Festival in the ‘60s, and managed Bearsville Sound Studio in Woodstock, New York in the ‘70s. After moving to Nashville, Rooney released a series of solo albums and produced the likes of Townes Van Zandt, Hal Ketchum, Bonnie Raitt, and others. In recognition for his contribution to Americana music, he received a lifetime achievement award from the Americana Music Association in 2009.

Well, Muddy Waters, and Bill Monroe. It’s real music that is made by real people, and it was just incredible. My brother was listening to blues, Memphis Slim, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Slim Harpo, and Blind Lemon Jefferson, and he also was listening to Hank Williams. He liked to sing like Hank Williams and do the blues. At the age of 16 or 17 years old, I got his guitar, and played with him for six months, learning what he showed me. That was kind of not fun. Then I saw the Dillards in an Orange County club, and the Dillards just woke me up, and I just had to get a banjo, and I started playing banjo 8 and 10 hours a day

About a quarter century after you first saw the Dillards perform, as a director, you vividly captured them with a splendid video documentary “The Dillards – A Night In the Ozarks,” released in 2006. The original Dillards — guitarist Rodney Dillard, his banjo-playing brother Doug, mandolinist Dean Webb, and bassist Mitch Jayne are seen playing originals and standards on porches and in living rooms of a Salem, Missouri farmhouse in the late ’80s.

The Dillards were so influential to a generation of young players. Among the first bluegrass groups to have electrified their instruments in the mid-1960s, they were pretty advanced progressive bluegrass for the time.

The Dillards were a driving force in modernizing and popularizing the sound of bluegrass in the 1960s and ‘70s, and they are credited with helping set the stage for the “country rock” movement and the burgeoning progressive sounds of bluegrass. Their first three albums include original songs that have become bluegrass standards like “The Old Home Place,” “Dooley,” “Doug’s Tune,” “Banjo in the Holler” and “There is a Time.”

Brothers Doug and Rodney played members of a family band, the Darlings, making 6 appearances on “The Andy Griffith Show” between 1963 and 1966. Joined by their jug-playing patriarch Briscoe Darling (actor Denver Pyle) and sister, Charlene (actress Maggie Peterson), the Darlings introduced bluegrass to many Americans.

Well, I had to do that. I put it together because I wouldn’t be talking to you if it hadn’t been for Rodney, and Doug Dillard. Rodney is a lifetime friend. They believed in me. They took a chance. I was away from the Dirt Band at the time, and I called up Mike Denecke and asked him if he would do sound.

It’s interesting reading in your book that Roy Acuff wasn’t sure he wanted to play on the first “Circle” album. And there he is in the control room listening to the music. After it was done, he said, “That’s country music. Let’s go make some more.”

I met Roy and was around him for a week at the Grand Ole Opry in the late ‘70s. I often saw Roy backstage that week, and he looked like a real old man. He shuffled around. Yet, when he went onstage, he was like a spring chicken of 25. He just came alive. I’ve never seen a transformation quite like that.

Yeah, I noticed that with Roy Acuff, and with Porter Wagoner too. Same thing. One time Porter was coming off stage at the Opry, and I said, “Hey Porter how you doing?” He said, “Oh, I’m a little bit worn out. It’s been a long day. What did you want John?” I had gotten to know him. I said, “My in-laws are here, and they were hoping to get a picture with you, but I won’t bother you with it.” He was like, “Oh, where are they? Get them to come over and get a picture.” He perked up, and looked like he was just fresh out of something. “Okay good, you got it?” We got the picture, and he was like, “I gotta go change my clothes now.”

“Will The Circle Be Unbroken” was Mother Maybelle Carter’s first gold record.

Yes, I gave it to her. I took it to her house. Marty Stuart went with me. I didn’t know where she lived, and he did. “Maybelle, this record I want to give it to you because you are part of the reason that it is a gold record. Thank you for being with us.” She replied, “Well, I’ll be. I never had one of these.” If she stayed alive, she would have received a platinum record. But that was quite an honor to give that to her. And then she stood it against the wall, and she said, “Would you boys like some lemonade?”I said, “Well, Maybelle Carter if you are going to fix me lemonade, then I am going to drink it.” You know that she called us, “Them dirty boys.”

I am surprised that Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash didn’t sneak into the first “Circle” album sessions. To hear Johnny’s dedication of “Tears in the Holsten River” to his mother-in-law Maybelle Carter, and her sister Sara on the third “Circle” volume, released in 2002, is to have the Carter Family made real.

Well, they were on the road. It was in August, and we didn’t know them yet. But I’ll tell you if you want to get to know somebody, make a great album with their mother-in-law or their mother. Johnny Cash, when I met him he said, “Let me thank you boys for doing that for Maybelle. That was wonderful.”

He was all over the “Circle” album. In fact, when we did “Will The Circle Be Unbroken: Volume 3” (2002), he called the studio, and we were all there, and he said, “I would like to be part of this record. Would you be my band?” Having Johnny Cash ask would you be his band was really exciting.

At the peak of their country career, the Dirt Band toured Europe with Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash, who hinted that they’d love to appear on a sequel to “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” if the band ever decided to make one. That gesture convinced the band to get back in the studio to record two follow-up all-star “Circle” albums.

Bluegrass patriarch Bill Monroe, who perfected his music in the late 1940’s and stubbornly maintained it, refused to be on the original “Will The Circle Be Unbroken.” However, he eventually told you he’d like to be invited.

Bill Monroe wasn’t on any of the “Circle” recordings. When I asked him first, he just didn’t know. Bill Monroe didn’t know any music but Bill Monroe music. He didn’t listen to the radio. He didn’t listen to what he called rock and roll. “It ain’t part of nothing.” We were on the record charts with “Mr. Bojangles” (inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2010), “Shelley’s Blues” and “House of Pooh Corner” so he knew we were on the charts with the Doors, the Beatles, and Nashville Brass, and whatever. He thought we’d put a snare drum and horns and electric guitar all over his music. And Bill came up to me at a festival a few years later, and he said, “Hey John, if you ever do another of those ‘Circle” albums give me a call.”

Vasser Clements told me so many Bill Monroe stories. Like Bill leaving players in small towns because they were late getting on the band bus.

If you ever needed a fiddle player who could do it all, you had to get Vassar. Someone who could play jazz like Stéphane Grappelli and could also play bluegrass and old-timey country music.

You played shows with Earl, Gary and Randy Scruggs, Josh Graves, and Vasser.

That was a good group, The Earl Scruggs Revue. I played with Vasser so many times. I hired him to work with me 25 times over the years after the “Circle” album, and it was wonderful. One night I asked him, “Vasser, how do you play ‘Uncle Pen?” And he played it, and I said, “That sounds like that Bill Monroe record.” And he said, “John that was me. I was 17 years old.”

I have over 25 Nitty Gritty Dirt Band albums in my collection, and I think four compilations. I still have a vinyl copy of the first self-named album released in 1967. I remember the single “Buy for Me the Rain” co-written by a pair of rising California songwriters, Steve Noonan, and Greg Copeland. There’s pair of Jackson Browne-penned songs, “Melissa” and “Holding.”

“Buy for Me the Rain” has been used forever as the main theme for the long-running agriculture and agribusiness magazine TV program “Market To Market,” produced by Iowa PBS.

Not many groups that I am 20 albums deep with.

I’m on all those so I appreciate all that. I was there for 50 years, and at the end of the 50th year tour, I stepped off the bus, and I said, “Have fun. I gotta do my own shows.” We weren’t doing enough “Circle” music. One or two songs and I wasn’t driving the train. It was a democratic group. And I just got outvoted. “Hey, why don’t we do……” and I’d mention a song, and we might work on it, and try it once. We just never did, really.

You must concede that the band shifted direction several times over the years as it changed members, and jumped labels to Warner Bros., MCA, Capitol Nashville, Warner Nashville, and DreamWorks with indie label sojourns on DualTone, and Sugarhill.

While the band continued to record old-time country music, both on their own and with Alison Krauss and others in the ‘80s, recordings like “An American Dream” with Linda Ronstadt, and “Make a Little Magic,” with Nicolette Larson, as well as their more mainstream country songs, “Long Hard Road (Sharecropper’s Dream),” “Baby’s Got a Hold on Me,” and particularily, “Fishin’ in the Dark,” went a long way in redefining the band’s identity.

That was the string of 20 country hits, and that was the first record I was not on. About a year and a half after I left, I was really glad to hear “Fishin’ in the Dark” because it was like your old alma mater had won the game. I had people asking me, “Hey, now that you aren’t in the Dirt Band, what are they going to do?” I said, “Look, the group is resilient. They will come up with something. Just hang out for a bit.” And they did come up with something again and again, and I was really proud of them.

“Fishin’ in the Dark” reached #1 on the U.S. and Canadian country charts. It was co-written by my friend Jim Photoglo. A former pop artist with two charting albums in the ‘80s, Jim has been a highly successful Nashville songwriter for decadesand was one of a member of the short-lived novelty country band Run C&W.

Jim has been playing bass with the band now (since 2016), and he and Wendy Waldman with Fishin’ in the Dark” wrote a fine song for the Dirt Band/

Your brother Bill produced Steve Martin’s novelty hit “King Tut” with backup by the Toot Uncommons. I remember it first being performed on “Saturday Night Live.”

Well, that was the Dirt Band. My brother was managing Steve at the time.

“King Tut” was released as a single in 1978, sold over a million copies, and reached #17 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. The song was also included on Martin’s 1978 album “A Wild and Crazy Guy” which won the Grammy Award in 1979 for Best Comedy Album. Bill also produced Steven Wright’s album “I Have a Pony.”

In 2015, “A Wild and Crazy Guy.” was deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Recording Registry.

It was Bill and your fate to be far more than routinely successful.

Bill’s fast-burning energies, his versatility, and his profuse gifts for music, photography, and film coalesced to make him a high-profile figure in numerous fields, among them music production, films, and television.

Through the Aspen Film Society, the production company he co-founded with Steve Martin in 1976, Bill was a producer or executive producer for numerous films, most notably as the producer for “The Jerk” (1979), “The Man with Two Brains (1983), and “The Big Picture” (1989), and executive producer for “Pee-wee’s Big Adventure (1985).

As the younger brother, you have scored 13 film projects, including Steve Martin’s NBC television specials as well as the score for the 10-hour epic Warner Bros. television mini-series “The Wild West,” the Emmy-nominated documentary that chronicles the Old American West from 1866 to 1896.

As project producer, you were awarded the coveted Western Heritage Award that honors individuals who have made significant contributions to Western heritage through creative works.

What was in your family DNA that led to you two mastering all of this creative work?

I guess I was bored. There’s nothing in the DNA.

Your parents were probably less than enthusiastic when Bill and then you channeled your energies into music, and film.

My father told my brother when he started going up to Hollywood to learn the record business, “Why do you want to know those people?”

What did your parents do for a living?

My mother was a mother. A housewife. My father ran a diesel equipment business, a surplus business. He’d buy stuff from government auctions, Navy and Army and whatever equipment. Jimmy 6-71 engines, and 4-71 engines. 6-71 means 6 cylinders in a 71 series.

The classic Detroit Diesel two-stroke 6-71 design, tuned for commercial duty, produced 165 horsepower and sounded like it was revving twice as fast as it really was, resulting in its nickname the “Screaming Jimmy.”

He’d buy bearings. He’d buy generators. He had a 110,000-square-foot warehouse in Long Beach, and he made a living in a business that ended up dying out. He was an interesting character.

You became part of the L.A. music scene at an interesting time as America’s music industry transitioned away from New York to the City of Angels.

The result was the music business rebounded from there with new locally based labels. including A&M, Elektra, Dunhill, Straight, joining Reprise Dot, Keen, Del-Fi, Modern/Crown, Specialty, and United Artists.

Groups like the Buffalo Springfield, the Byrds, the Rising Sons, (with Taj Mahal, Ry Cooder, and David Lindley), the Doors, Love, Steppenwolf, Three Dog Night, the Mamas & the Papas, and the Mothers of Invention. played such local clubs as The Troubadour, Whiskey A Go-Go, The Ash Grove, Pandora’s Box, Gazzarri’s, The Trip, Ciro’s, London Fog, The Balladeer, The Fifth Estate, and The Golden Bear in nearby Huntington Beach.

In your book “The Life I’ve Picked,” you wrote about your early days working at Disneyland Park in Anaheim when you were 16.

I worked in Fantasyland at Merlin’s Magic Shop about 1/10th of the three years, the rest being at Main Street Magic shop in between the Wurlitzer store and the old cinema that would show 6 silent films. Both shops were under license to a firm called Taylor & Hume.

Merlin’s Magic Shop faced the center courtyard in Fantasyland, adjacent to the Sleeping Beauty Castle. This small building has been home to many different themed shops over the years, including Mickey’s Christmas Chalet, the Castle Heraldry Shoppe, Briar Rose’s Cottage, the Villain’s Lair, and Castle Holiday Shoppe, and currently Merlin’s Marvelous Miscellany at Disneyland.

Steve Martin also worked at Merlin’s Magic Shop in Fantasyland.

Steve did, and it was the time of our lives. What a great gig for a 16 or 17-year-old 18-year-old. It was a time when groups were being booked there. There was a hootenanny night, and there was acoustic music. There were the Mad Mountain Ramblers, and the Pine Valley Boys played in Frontierland.

Steve and I would take our breaks at the same time. I would take longer-than-I-should-have breaks to catch David Lindley playing hot banjo with his cool group, the Mad Mountain Ramblers, and later, the Dry City Scat Band. You know, David always stood on his toes for solos.

You did eventually play Disneyland with the Dirt Band.

It was years later that we got a gig at Disneyland for a night.

(In the summer of ’61, David Lindley had formed the Mad Mountain Ramblers with schoolmates from La Salle High School, a private, Roman Catholic college preparatory high school in Pasadena.)

David, (multi-instrumentalist) Chris Darrow, and (violinist) Richard Greene were all in the Mad Mountain Ramblers. Chris ended up in the Dirt Band for a few years (contributing to the studio album “Rare Junk,” and the live album “Alive!,” recorded before the band went on hiatus in late 1968), and Richard went on to be a great musician (with Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys, the Blues Project, and Sea Train.) He was always a great musician.

David was totally five-string banjo in those days.

David was an early inspiration to me. He was also in the Rising Sons, and he went off to be a founding member of the even stranger Kaleidoscope band which released four albums on Epic Records, and then he worked with Jackson Browne a few years later and did that for 20 years.

David Lindley passed away on March 3rd, 2022, in Pomona, California where he had been in hospice care for a short period. His death was announced on his website. The announcement did not cite a cause, although he was said to have been battling double pneumonia, and acute vasculitis. He was 78.

I will never forget seeing David in 1966, a year after Disneyland when he was a judge at Southern California’s Topanga Banjo Fiddle Contest and Folk Festival. That really put pressure on one of the entrants: Me. After the contest, which I won, I took a lesson from him to learn the left-hand pull-off trick for “Arkansas Traveller.” Something I would continue to play my whole life.

I saw David once for one of his many times with Jackson Browne. I am sure Jackson is among those that miss David as I do.

Following David Lindley’s death, Jackson Browne posted a remembrance, “David is a very large part of me – who I became, and who I remain.”

Jackson played with David for the first time in a dressing room at the Troubadour in 1969. Jimmy Fadden of the Dirt Band brought David to say hello, and he pointed out that David had his fiddle with him, saying he would probably sit in if Jackson asked him to. Jackson already knew David from the band Kaleidoscope, whose first album, “Side Trips,” was one of his favorite records.

As Jackson recalled, “We started to play my song ‘These Days,’ and my world changed.”

One of your local club hangouts came to be The Ash Grove at 8162 Melrose Avenue in the Fairfax District of Los Angeles. one of America’s greatest folk and blues clubs of the ‘60s.

Ry Cooder’s first public performance was at The Ash Grove, formally a furniture factory and showroom that opened in 1958, as a guitarist backing Jackie DeShannon in 1963; he was 16. Linda Ronstadt got her start hanging out at The Ash Grove.

I saw David Lindley in Kaleidoscope at The Ash Grove in 1967. It is where I first heard Doc Boggs and his (1964) song “Oh, Death” (previously recorded by the Pace Jubilee Singers in 1927).

Among the performers that played The Ash Grove were country-styled Doc Watson, the Kentucky Colonels, the New Lost City Ramblers; blues giants Mance Lipscomb, Son House, Mississippi John Hurt, Buddy Guy, John Lee Hooker, Howlin’ Wolf, Albert King, Big Mama Thornton, and Jesse Fuller; and rising contemporary music performers Canned Heat, the Byrds, Bonnie Raitt, the Chamber Brothers, Maria Muldaur, and Spirit.

A fire in 1973 left nothing of The Ash Grove, but the shell of the building, it was remodeled into the Improv in 1974.

The title track of Dave Alvin’s 2004 album “Ashgrove” deftly sets his memories and the club’s history to music.

Nearly 60 years ago, Dick Dale’s rushing guitar lines energized a generation of California musicians. Surfers flocked to the waves along Newport Beach, and Dick Dale and the Del-Tones packed over 3,000 people nightly into the Rendezvous Ballroom on the Balboa Peninsula.

Were you one of those who came to see Dick Dale double-pick faster and faster, like a locomotive, to re-enact the power of surfing the waves, before the Rendezvous Ballroom burnt down in 1966?

I listened to Dick Dale. I thought he was good. I went to see him one night at the Rendezvous Ballroom. I don’t remember the show. I do remember driving there with a friend who was driving. He drank practically a 12-pack of beer on the way there, and I’d throw the cans out the window.

Then there was simply no one better at sharp, fluid Telecaster licks and twin harmony than Buck Owens in tandem with singer-guitarist Don Rich.

I’m a California guy, and I dug Buck Owens. He was really singing it right. Thanks to Don Rich, he had a lot of hits. Don was the guy that sang that magic harmony with Buck Owens.

You couldn’t tell them apart.

No.

What is the bond or ingredient that has kept the Dirt Band rolling for 56 years? Most bands break apart after a few years as members go off and do other things. The Dirt Band give the impression of having a certain quality; seemingly able to pivot on a dime toward any musical direction they wish to travel.

Well, that is what constant members Jeff Hanna (singer/guitarist) and Jimmie Fadden (drummer) know what to do. They are the two that are still there from the original group.

I go out with Les Thompson, one of the original members. He’s the guy who called me in 1966 and said, “Hey, John why don’t you come and join this group that is getting together at the music store, (at McCabe’s Guitar Shop on Pico Boulevard in Santa Monica) I said, “I’ll listen.” I went and listened, played a few songs, and I said, “Okay.” I was 20 years old. Les was 16. and the other guys were 17, 18, and 19. And it worked. We worked, but we didn’t make any money for years.

In the mid-1970s Takoma Records had offices two doors east of McCabe’s and built a recording studio, with audio and video cables going from the sound booth at McCabe’s to the control room of the studio, which allowed easy recording of performances.

We used to hang out there. We used to avoid going to school. (laughs) After I got out of school, I would hitchhike there. Most of it was walking as a matter of fact. My friends became my friends that hung out there, There was a bunch of guys that hung out there, and were interested in playing instruments. They were interested in learning to develop a style and a vocabulary on the instrument of their choice.

Many male musicians join bands to attract girls.

That wasn’t my pursuit. Occasionally, it helped, sure. It wasn’t the reason. I wanted to go onstage and see if I was worth anything. See if I could do anything. See if that practicing that I had been doing for a couple of weeks, see if I could do those licks in front of people. That was the excitement to me.

It has been widely claimed that Jackson Browne had been an early member of the Dirt Band.

They had done five jobs with Jackson Browne, and now Jackson was out. He didn’t want to have them backing up his songs. He wanted to do (his songs) on his own, and they needed another player. Jackson used the band to back him up for some of his songs. He doesn’t mention that in his own bio on his own website. A couple of the Dirt Band guys have been harping on Jackson Browne for 50 years, and “Jackson was in the early Dirt Band” is one thing that irritated me. Well, you know they did five jobs, and he left. He wasn’t in the recording group. He wasn’t in any publicity pictures. Jackson is a fine guy. He sang with me a couple of times, and I appreciated it.

The first paying gig for the Dirt Band was playing The Golden Bear in Huntington Beach, California on April 4th, 1967, just after releasing their first album two months earlier.

Most importantly Bill had been brought in as the Dirt Band’s manager and was also the band’s producer until 1980.

I convinced my brother to start managing the band, and then I scheduled a rehearsal, “Hey we’ve got to rehearse,” and that was an arduous thing, but we did it. Les (Thompson) was always enthusiastic.

For the first 10 years, I was road managing also. So I didn’t have any time really. I’d be up an hour and a half before anybody, and I’d go to bed an hour later. I was driving to the gigs. “Okay everybody we are leaving at 8 in the morning.”

That was before cell phones. Road managers used to run off the airplane with a bag of quarters to the phone booth to call the hotel and car service and label.

It was exciting but it was tiring. It was exhausting. It was wonderful. It was all of those things.

Along the way the Dirt Band appeared on innumerable TV shows including “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson,” as well as shows hosted by Steve Allen, Joey Bishop, the Smothers Brothers, and Glen Campbell.

Everything there was to do, the Dirt Band did it.

They not only played with the Doors, but also did a 10-day tour opening for Bill Cosby that ended at Carnegie Hall, and opened for Little Richard in Las Vegas.

Yeah, we did a month with Little Richard at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas Three shows a night. We had what we called the (Dr.) Pepper Hour. We went on at 10, 2, and 4. The four in the morning show was tough.

So, we rehearsed a lot, and then we got the job on “Paint Your Wagon” and that was a four-month vacation up in Oregon shooting that movie.

It took the 1968 film “Paint Your Wagon” to briefly break up the Dirt Band. After three albums with no hits, the band auditioned and landed a job as musical miners in the Paramount picture, “Paint Your Wagon” filmed near Baker City, Oregon.

After four months on the “Paint Your Wagon” set, being frustrated by the long delays in the making of the film, the band decided to split up.

We’d been together a few years, and had done four albums, been in a movie, and that was a pretty good career. It was 1968. It seemed like 5 years had gone by from 1966 to then. “Buy For Me The Rain” was on the first album, and it was a minor hit, and then nothing.

With Its overblown $20 million budget, and nearly three-hour length, “Paint Your Wagon” was quite the horrible film.

Yeah. Horrible film? Some people think that “Paint Your Wagon” is the best film that they have ever seen. And some people think like you.

C’mon Clint Eastwood and Lee Marvin doing their own singing.

Yeah, it was pretty funny.

Despite “Paint Your Wagon” being regarded as a box office flop (which it really wasn’t), the soundtrack was a smash success. Orchestrated and arranged by Nelson Riddle, Lee Marvin’s version of “Wand’rin Star” became a #1 single in Ireland and the UK.

Then Jeff and I were at the Golden Bear watching Pogo (that became Poco), play and they were great. We looked at each other and said, “Let’s get the Dirt Band back together,”

Poco has been so overlooked in musical history despite the lineup of guitarists Richie Furay and Jim Messina (former members of Buffalo Springfield) multi-instrumentalist Rusty Young, bassist Randy Meisner, and drummer George Grantham.

So overlooked. Richie Furay was a great singer. Rusty Young was a great steel player, and they had Randy Meisner who ended up in the Eagles. And Jimmy Messina who went on to Loggins and Messina. They were really good. I went and got Les Thompson from next door to The Troubadour where Jimmie Fadden was working.

Jimmie was friends with Linda Ronstadt.

We all were. Linda was hanging out at The Troubadour. It was easy to be Linda’s friend. She’s a wonderful, nice person. She still is, but she can’t sing anymore and she’s living in San Francisco.

It breaks my heart that Linda can no longer sing.

Well, she accepts it. She’s done some concerts where she talks about the past, using footage of film and stuff, and it works really well.

I was at a Linda Ronstadt recording session on Ventura Boulevard in the Valley and it was about 1 A.M. and I’m sitting in the vocal booth with headphones on listening to the playbacks. Linda said, “I have to do a vocal on a song.” I said, “Okay I’ll leave.” She said, “No, give me the headphones. and stay.” So I did and she sang “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow.” And she’s singing it to me. And I’m going, “Yes I will.” And she just ripped that song apart. It’s the best version in my opinion.

Engineer Mike Denecke continued to do interesting projects with you.

Mike was an amazing friend. He was the engineer on “Mr. Bojangles” when I met him. And he recorded the Dillards. Two microphones to record that whole thing. Live music. He was funny. “Mike, how long will it take you to set up?” He’d answer, “Fifteen minutes.” I’d go up to him 18 minutes later and ask how long he’d be. He’d say, “I was ready three minutes ago.” And he was ready. Mike believed in simplicity. He did a great job.

Mike was our location engineer for the “Miner’s Night Out” video, and he recorded a live album (in 1999 as John McEuen & the L.A. String Wizard) called “Round Trip” recorded on a NAGRA-D four-channel digital audio recorder with no overdubs. It really sounds good.

Mike went on to invent the Denecke Time Code slate.

The Denecke Time Code slate assigns a unique number to each image or audio frame.

It makes film cameras run at 24 frames per second, a tape recorder that runs at 15 inches per second, and a video camera that runs at 29.9 frames per second. Timecode made it able for all of those machines to lock together, and run at the same time. You didn’t have to use three reels of film anymore. A reel of film would be for the movie sound. A reel of film for sound effects; and a reel of film or music. And they had to run in sync with each other. But Timecode eliminated that.

“Round Trip” was recorded at The Ash Grove and features your son Jonathan on guitar and vocals.

He did that after driving straight from Denver to Santa Monica, and he was on stage an hour after he arrived, and he played well. He amazed me.

For a good part of your career, you were a single parent raising 6 children, 5 of them boys.

Oh man, yeah. My daughter was first. She was the babysitter

You took the kids on the road with you?

Oh yeah, when I got divorced after 18 years, I still had to work. So weekends with dad it would be “Where are we going, dad?” I’d say, “Why don’t we go to Durango and Steamboat? And I would book jobs in ski areas where I’d get jobs with rooms and food and so much money. My kids would ski for free, and they would stay for free. They probably skied 15 ski areas. Then I’d go to other jobs. I would play Branson, Missouri, and the Minneapolis State Fair in St. Paul, and things like that.

There were a lot of fun times on the road.

But it was also a lot of work. I was driving. This wasn’t first-class. I was out of the band. I left in the 90s because I was getting divorced. I think it’s the band’s fault. The first night I separated from my wife, the mother of my 6 children, I went into a grocery store in Colorado at midnight to get something to eat. And “Mr. Bojangles” came on the radio system. So I turned around and left. I couldn’t take it. So that was an interesting head change. That was.

How many grandchildren do you have?

Eight grandchildren, and one great-grandchild. Amazing. My daughter had a daughter, and her three girls are 32, 30, and 29. And the 29-year-old had a kid.

You posted a photo on Facebook of you with your great-grandson Mel looking at your tour schedule with your caption, “See grandpa pick… see granpa fly to West Yarmouth for concert.”

He is a great kid. Loves trucks and airplanes. . . and dinosaurs.

Do you spoil all of the kids?

I do when I see them.

Larry LeBlanc is widely recognized as one of the leading music industry journalists in the world. Before joining CelebrityAccess in 2008 as senior editor, he was the Canadian bureau chief of Billboard from 1991-2007 and Canadian editor of Record World from 1970-80. He was also a co-founder of the late Canadian music trade, The Record.

He has been quoted on music industry issues in hundreds of publications including Time, Forbes, and the London Times. He is co-author of the book “Music From Far And Wide,” and a Lifetime Member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

He is the recipient of the 2013 Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award, recognizing individuals who have made an impact on the Canadian music industry.