This week In the Hot Seat with Larry LeBlanc: Holly Gleason, artist development consultant and music critic.

The brash, wildly talented Nashville-based journalist, author, and artist development consultant Holly Gleason was presented with the CMA Media Achievement Award in 2019.

Gleason’s formidable knowledge of American country music, and rock and roll allows her to write from a place of deep knowledge. Not only understanding an artist’s music, but also their life moments, and the cultural and historic place that they hold.

Gleason grew up in Shaker Heights. Cleveland, fully embracing its ‘70s music scene as an underage kid bringing her fake ID, and English homework to local clubs, buying cheap records, and being knocked sidewise discovering country music’s original badass, Merle Haggard.

While studying communications and broadcast management at the University of Miami, she landed a job as the South Florida market correspondent for the live music trade, Performance. She also began writing for such niché publications as Grapevine, In Record Timez, and nationally for Rock & Soul.

After a stint freelancing at the Miami Herald and then working at the Palm Beach Post, Gleason went on to become one of America’s most prolific music freelancers.

Over the years she has contributed music articles to the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Tower Pulse, Mix, Country Song Round-up, Rolling Stone, the Los Angles Times, Billboard, New York Times, Oxford American, No Depression, Paste, Lone Star Music, Texas Music, Spin, Music Express, Musician, Creem, Interview, Playboy, Request, Rockbill, Bam, Harpers Bazaar, Saturday Evening Post, and American Songwriter.

Gleason currently is the Nashville Editor and Sr. Contributing Editor to Pollstar, and HITS/HITSDailyDouble.com, and contributes to Variety, CMA Close-Up, NPR, The Contributor, and the International Network of Street Papers.

From 1990 through 1993, Gleason worked as the head of media and artist development for Sony Music Nashville and subsequently founded Joe’s Garage, a Nashville-based public relations, and artist development agency.

She oversaw development projects and publicity for John Prine, Rodney Crowell, Asleep at the Wheel, Lee Ann Womack, Patty Loveless, Montgomery Gentry, Brooks & Dunn, Terri Clark, and Kenny Chesney.

While working as Chesney’s publicist, Gleason co-wrote “Better As A Memory,” a #1 hit in 2008 on the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart for Chesney, under the pen name Lady Goodman, a character in the Cameron Crowe 2000 film, “Almost Famous.” She has also co-written with Guy Clark, Rodney Crowell, Bill Deasy, Charlie Pickett, Jim Lauderdale, and Matraca Berg.

Nearly a decade ago, Gleason returned to school to earn a Masters’ in Fine Arts from Spalding University in Louisville, Kentucky.

Gleason edited country music’s game-changing book, “Woman Walk the Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives,” published in 2017 by the University of Texas Press as part of its American Music Series.

A collection of inspirational essays by 27 female contributors on the artists that inspired them, this isn’t your usual anthology of profiles. Gleason selected contributors based on their skill, and their depth of connection to the story they sought to tell.

The book includes a brilliant essay by Taylor Swift about ‘50s country and pop star Brenda Lee, while Rosanne Cash contributed the eulogy she gave in 2003 at her stepmother June Carter Cash’s funeral, and Grace Potter wrote about Linda Ronstadt.

In the book, writer Madison Vain argues that Loretta Lynn was country music’s Queen of the Sexual Revolution.

Transgender writer Deborah Sprague details the acceptance she felt from Rosanne Cash.

Singer/songwriter Kim Ruehl, a 9/11 survivor, describes how Patty Griffin’s music helped her beat her post-traumatic stress disorder and move forward.

TV producer Nancy Harrison writes about discovering Dolly Parton on the radio as a teenager, and realizing, as a young “satin pants wearing” Long Island teenager that girls can write their own stories inspired by Parton’s “9 To 5” hit recording, and film.

Woman Walk the Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives,” is slated to be released in softcover in October, 2021 by the University of Texas Press

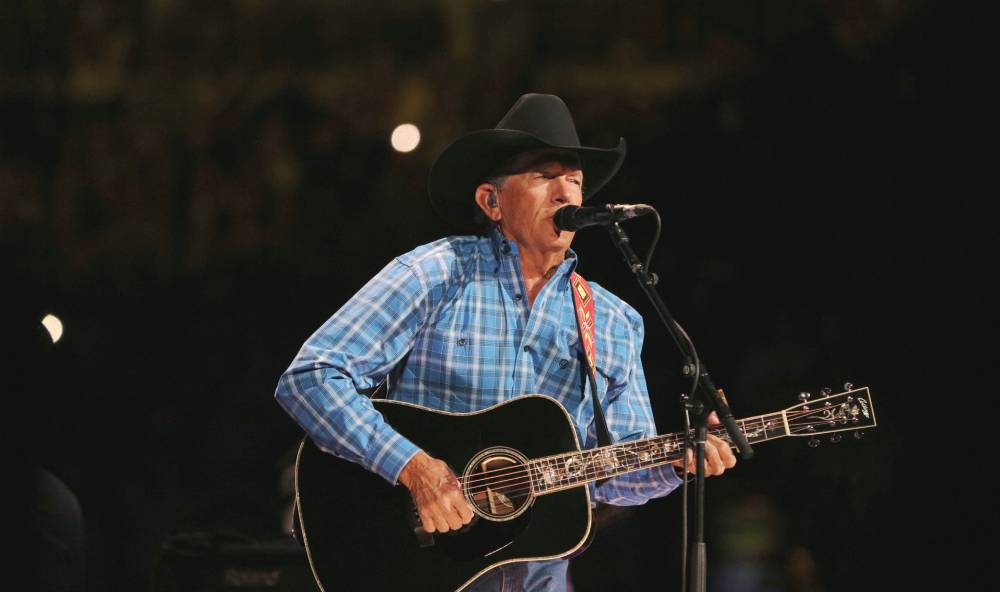

In 2019, Miranda Lambert presented you with the CMA Media Achievement Award during the 2019 CMA Awards show at Bridgestone Arena in Nashville. It is an industry-voted award, recognizing the media person whose work has done the most to expand the reach and understanding of country music over the past year.

The irony is that I had been nominated three times. I am a polarizing figure, and it is voted on by publicists. The year (1989) I lost to Bob Claypool (the author/columnist with the Houston Post), he had just died, and I think that if I had been voting, I would have voted for Bob Claypool because he was awesome.

Bob was a hard-drinking country music journalist who used to ride around in an old Lincoln with Dwight Yoakam before Dwight broke through. Like you, he was ornery and opinionated.

The award might have come earlier to you.

In those years that I was writing for Rolling Stone, Creem, and Mix, I was doing the work, and I didn’t win it. At that point, it would have been game changing for me. So I let go of it. As a writer, I was really successful. I was working for the Los Angeles Times, the Miami Herald, and the Cleveland Plains Dealer.

While still in college, you became a music critic for the Miami Herald and other publications. Over the years, you have freelanced for so many consumer, and trade publications and radio outlets. You obviously are focused, and tenacious.

Not only am I that tenacious, but I paid for college as a freelancer writer. When you have to pay your bills, you get down on it. The other thing was I was really good at doing interviews because I had done so many interviews as a kid (as an amateur junior golfer). I knew how to be likeable for TV. I knew how to be all about the artist because I saw what the guys I didn’t like did. I also knew how to listen. To pick up on what they (artists) were saying, follow their trail, and do my research. So I was a pretty good interviewer, and because I was so young, if you met me you never forgot me.

Although some of the same structural problems existed as you were emerging as a top journalist, country music was becoming more progressive in its sound and outlook. You and several other journalists brought a very personal lens to the genre, exploring how artists were faring with the changes while transitioning to popular mainstream performances at a time many national American consumer publications couldn’t quite grasp the significance.

Meanwhile, there were only a handful of journalists heralding country music among a broader audiences in the United States and elsewhere, including early author/journalists Chet Flippo and his wife Martha Hume, who both died in 2013

It is funny you mention Chet and Martha because I remember my first Fan Fair at the fairgrounds as a 19-year old freelancing for the Miami Herald. Chet’s book “On the Road With the Rolling Stones: 20 Years of Lipstick, Handcuffs, and Chemicals” was a recent paperback, and publicist Liz Thiels asked if I’d be interested in interviewing Chet Flippo. I remember trying to breathe evenly walking up to the door of Liz Thiels’ sun-filled place. I stayed an extra day so I could talk to Chet. He was one of my heroes because he got that you can take something from the fringe, write about it like it’s right smack dab in the middle of rock and roll if you honor it for what it is. He didn’t bring that rock and roll thing to it. He brought the full frontal of rock writing. He wrote about Willie (Nelson), and what Willie was. He wrote about Tanya (Tucker) and what Tanya was. He wrote about Dolly (Parton).

Among Chet’s more famous articles was a 1980 cover story on Dolly Parton. Overcome a bit by her, he asked Dolly if she would run away with him as his first question. Her answer was, “If you’re ready, but let’s wait and see how much money you make from your book.”

Chet talked about the glory days of Rolling Stone (magazine); and about writing his 1981 Hank Williams’ biography, “Your Cheating Heart,” and the wild days of the Rolling Stones. He also talked about the craft of writing and reporting, balancing enthusiasm with critical distance, and he indulged my questions about his wife Martha Hume’s (1982) book, “You’re So Cold I’m Turning Blue,” that, in many ways, informed my voice as a critic

You asked for an autograph. Chet signed your Rolling Stones’ book in black Sharpie with the coda, “Whips & Chains & Lipstick Stains.”

Yes, which made me laugh. Chet was so sweet. I had such a crush on him.

I knew Chet from being a stringer for Rolling Stone and then as Billboard’s Nashville bureau chief, and for his “Nashville Skyline” CMT reports.

I remember Chet stopping dead a Billboard trivia night in Miami in the mid-‘90s when various editors were swapping stories. We went around the table, and finally Chet had his say. He ended the night abruptly by adding, ‘Well, I’ve heard your stories, and they are all good. I only have one. In 1951, my mama and daddy took me to Ft. Worth, Texas to see Hank Williams play.’ For a music journalist, that’s like holding five aces. Nobody followed that. It was like, ‘Waiter, can we have the check?’

Unquestionably, it was quite rough early on being a female music writer. Among the trailblazers were: Lisa Robinson, Toby Goldstein, Gina Arnold, Gerri Hirshey, Barbara Charone, Sylvie Simmons, Ellen Sander, Ellen Willis, Jaan Uhelszki, Susan Whitall, Melinda Newman, Gail Mitchell, Deborah Evans Price, Evelyn McDonnell, Elysa Gardner, and Ann Powers in America; and Julie Burchill, Mary Harron, Caroline Coon, Penny Valentine, and Vivien Goldman in the UK.

Shout outs should also go Australian author Lillian Roxon (“Lillian Roxon’s Rock Encyclopedia” (1969); to the trailblazing country music publicist and journalist Hazel Smith; and Jane Scott from Cleveland, and Ronni Lundy from Louisville.

“I think the biggest misconception about female music journalists — a stereotype perpetuated through their portrayal in film — is that they all got into the business as a way to meet, and, of course, sleep with, sexy male rock stars,” says Lyndsey Parker, music editor for Yahoo Entertainment. “Another common media trope is that they use their feminine wiles to get a scoop or gain access.”

I can’t speak to anyone else’s experience. I had fewer problems with artists, and publicists because I set myself up as every band in America’s big sister. I really was (Rolling Stone journalist and filmmaker) Cameron Crowe.

And I looked like a young teenager. I would go to do interviews and, if I went with a friend, and we were going to get lunch afterward, they (the tour manager ) would say to my friend, “Holly Gleason, nice to meet you. Let’s take you on the bus.” And the friend would go, “Okay, but I don’t know anything about music. I’m just waiting for Holly. Yeah, it’s her.” So I really had that young kid thing, but the newsroom deal, maybe, that was a little bit of it (chauvinism). I know that a guy that got one of my jobs was very jealous.

Being successful as a journalist in securing top-name interviews often comes down to building contacts and close relationships. You were doing both consumer and music trade journalism early on, including writing for HITS, Billboard, and Performance. Those music trade affiliations would have given you an advantaged inside edge. You became part of a music industry family. You were no longer a civilian outsider as most journalists were.

That’s interesting. I think that you are right. Because I started with the trade thing—I was doing a little bit of work for Billboard, and Performance. I was in the settlement for the Jacksons’ “Victory” tour when they played Miami (on Nov. 2nd, 1984). God was that an education. I was sitting there watching them do it. “Oh my God.” Things that you don’t think about. I also was writing for Rock & Soul and for Black Miami Weekly. I was a kid, and I could kind of float around, and people would laugh at me, at times. I was so young. And I was blessed. I was super blessed. God gave me a gift and I have worked really hard to refine it and protect it.

You have taught classes in rock criticism at Middle Tennessee State University. What did that involve?

Well in teaching music criticism today, kids are not growing up reading Rolling Stone, Creem, or whatever like we did. There was a lot of great music writing to go and find in our day. Today, it’s a lot about how do you assess it (the music). What are you looking at? Mostly, what you are getting (from the students) is, “Well, I like everything.”

That attitude is so evident in today’s music journalism at newspapers, magazines, and online blogs.

I would say this about criticism, and it’s important. Realistically I think that there was a challenge for me at the Miami Herald back in the day. I had started writing for the Herald as a sophomore in college—that, to me, defines criticism.

I had a really cool editor at the Miami Herald, Doug Adrianson, who taught me lessons, unintentionally. I don’t think that he set out to humiliate me, but I walked away humiliated a lot. I was given a record by a woman named Hillary Kanter. It was an okay review. I compared her favorably to an artist that, if you read me regularly, you’d know I didn’t care for. It was a softball (review). I was 19 years old. Doug came to me, and held the review up, and said, “Have you listened to this record since you turned in this review?” I replied, “Well, not really.” So he goes, “Hmm, really? So you are telling us that we would like this record. But I can’t even imagine that. This is something that you would never like.”

He knew some of the names that I had dropped.

“And I said, “Well, you know.” He goes, “No. I want to know. I want to know right now.” And, I was red in the face, and I had to confess to him that I knew that her parents lived on Miami Beach. They were people of some means, and they had paid for Rogers & Cowan to be the publicity PR firm, and Rogers & Cowan were a pretty big deal then, as you remember. The publicist had kind of strong-armed me.

This is when I learned you can’t play that (favor) game.

Doug Adrianson then said the most important thing to me, and I quote, and it could be on my tombstone, “You are pretty good at what you do, and I think that people are going to pay attention to you, but every time you do something like this you dent your name, and that is when the botulism sets in. And pretty soon your name isn’t worth anything.”

He also said, “If you give people better reviews than they deserve, you start to destroy their trust. Right now, they care what you think about Ricky Skaggs, but too much of that kind of thing, and they won’t.”

Also one of the things that people don’t take into consideration with music writing, of music criticism, is that an opinion is not criticism. There’s no real thought with an opinion. When Ann Powers or Jewly Hight write something for NPR, they have really taken time to consider it. They step out of the bias that they are sitting in to think about, “What does this really mean?”

I see lots of people with the women in country stories, and the racism in country music stories, they have already decided, “This is what it is, and I am going to report this.” And that’s not criticism, and it’s not informed.

Where you and I came up (as music journalists) is that you may think you might know what the story is and, all of a sudden it flips over, and you are like, “crap.” And there’s more work when that happens because you have to finish the reporting. The importance is both from artist development; like we talk about publicists and marketers, from that side of the fence; and even from the fan side. That good music writing should respect the fan enough to know that you want to give them depth, context, and meaning. It’s not what they (the subject) had for breakfast. It’s not how to keep their kids on Instagram. It’s not how hot their wife is or how buff their husband is. It’s what shaped this person.

That was beyond the novelty of how young I was; that is what I think is what makes them talk to me the second time being how considerate I am in doing interviews or when I write about a record.

And I had grown up with music writers like Jane Scott.

(Jane Scott’s “What’s Happening” column was a mainstay in The Plain Dealer’s Friday magazine in Cleveland for decades. She used the column to announce new shows and to shine the spotlight on favorite artists. She spent more than 50 years working at The Plain Dealer and was the newspaper’s principal rock critic from the day The Beatles played Cleveland in 1964 until her retirement in 2002.)

I was reading Jane Scott when I was a kid. She was not only the first music critic at the Cleveland Plain Dealer, but she knew that she served as a bridge between us, the fans as the readers, and the rock stars who came through Cleveland. David Bowie, Bruce Springsteen, Jackson Browne, Lou Reed – they all loved her and told her things. And Jane was also so generous with readers. I was one of many who would call her up, ask questions, and chat with her at her desk. It was a tremendous way to understand writing about humanity in the music.

Hearing firsthand about the craft of writing from the old hands still around while we were starting out was so helpful.

I saw how committed they were to what they did. What they were bringing to it and what is it that it is saying; because there’s a different template for Johnny Paycheck and Johnny Cash. Your job, as a critic, is to look at it in that global perspective. Not to be so snide like pretending that the music sucks or are we are going to dismiss Johnny Paycheck because he’s kind of a dirtbag. Because you get into fantasizing stuff, and that is not what we are talking about.

You are younger than I am, but our experiences are similar. We are both part of a generation of music journalists often embedded with the artists we were covering, particularly touring on the road. You are a music trade journalist from your earliest days. You weren’t just dropping by for a 20-minute chat with the artist. You went out on tours, and…

Let me stop you. By the time I came around, actually what I had was very real. I can remember the 20-minute interviews. I call them the “veal crate interviews” because it’s like this young calf that has no clue or choice. But there it is. Artists sit there, and they trot us in and out. I remember doing the interviews for the first Trio album (the first collaborative studio album by Emmylou Harris, Dolly Parton, and Linda Ronstadt, released in 1987). I remember four women in Nashville who threw—pardon my language—a shit hemorrhage– at the end of the day at Ronna Rubin (national director of press and artist development for Warner Bros. Records Nashville) about why did I get one of those slots because they deserved it? And the truth is that it was Bob Merlis in L.A. (long associated with Warner Bros. Records where he worked for almost 30 years, ultimately as Senior VP, Worldwide Corporate Communications until departing in 2001). I had already been on the road with Neil Young, and Neil had liked me and did an interview with me for Tower Pulse. Neil Young did three interviews for that album, “Old Ways” I always believed my work with Neil got me on the equally short list for the Dolly/Linda/Emmylou album.

What media outlets did you have in place for covering the Trio interview?

I had a string of publications where the stories would run including Tower Pulse, Palm Beach Post, MIX, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Illinois Entertainer, Rockbill, Country Song Round-Up, Tune-In The Radio fanzine, THE Cox Wire, Serviice including the Miami News and Atlanta Journal-Constitution), and Music (Tampa/St Pete and Orlando editions). Writing 11 different stories about that magical record was so much fun.

You lived in the glory days (of rock journalism). You really did live in times when you were embedded. And I see it with songwriters we assume we know because we hear backroom conversations.

Well, as a music trade journalist, and as a label publicist, you got to hang out with Kenny Chesney John Prine, Asleep at the Wheel, Lee Ann Womack Patty Loveless, Brooks & Dunn, Montgomery Gentry. and Terri Clark.

You’ve written songs with Guy Clark, Rodney Crowell, Matraca Berg, Travis Hill, Bill Deasy, Charlie Pickett, and Jim Lauderdale.

Quite different experiences from being a newspaper or magazine staffer seeking interviews from publicists or management.

Well, yeah.

And it becomes a very, very fine line in keeping your journalistic integrity, and not going over to the other side. It’s something I understand also because I’ve had to deal with it myself being a music trade journalist and former publicist.

Well, I would also say that I’ve heard that. I think that if you are genuinely friendly with an artist, if you are someone who crosses a semi-permeable membrane, right? Where they play you songs or share their fears. Keith Whitley used to call me to talk about alcoholism because I had an alcoholic father. A bad alcoholic father. And he had kids.

The bottom line is you have to tell the truth.

I’ll tell you a story that happened with covering Southern Pacific at the Celebrity Theatre in Anaheim, California. I was doing the show for the L.A. Times. Holly Dunn and Southern Pacific. If I am the next wave of “Almost Famous,” which (director) Cameron Crowe has said that I am, one of my Stillwaters (the name of the band in “Almost Famous”) was Southern Pacific with Keith Knudsen and John McFee from the Doobie Brothers, and Stu Cook of Creedence Clearwater Revival. They were like my big brothers.

What happened?

They played the worst set that I’d ever seen or heard. It was dreadful. And I didn’t have my laminate with me, and I had to go find the tour manager. He said, “What are you doing here?” I said I have to see the guys, and I have to see them fast because I have to get back out there for Holly Dunn.” Down the hall I walked, and they all see me with that face, and I’m probably 22 or 23, and Keith Knudsen, God bless him, said, “Hey, what’s up?” And I was like, “I don’t know what the hell I saw out there. It was a train wreck. I don’t even know what I just saw but in 36 hours that (review) is going to be in your driveway.” Because that was back when everybody got their daily paper.

What was the reaction?

Everybody looked at everybody. There was a pregnant moment, and Keith Knudsen said, “Well, it wasn’t our finest hour. But do what you gotta do.” I replied, “Okay, but right now I’ve gotta go and see Holly Dunn.” And I ran away. I couldn’t not tell the truth. I think the skunky thing would have been for them to pick up the paper and see Holly Gleason with this crappy review.

That would have been horrible.

I don’t know that people that write about artists can understand their (artists) context or their conflict if they don’t have access. But I also know that most people think that they understand long before they have enough information to make up their mind. And that’s the danger.

Journalists interview touring artists and conclude that, if they have a relationship with them, they will get a unique interview. In truth, they are a friendly journalist in that specific city. The artist moves on and meets up with another friendly journalist in the next city who feels the same way.

I know from long experience that publicists let journalists only know what they want them to know. Journalists might get access, but not full access, unless they are on the road with the artist for some times, where it is more difficult to maintain control.

Working as a journalist in the Nashville “bubble” may be a different paradigm, as would, perhaps, working in New York and L.A. But elsewhere, no matter how good a journalist you are, you are only getting a few minutes of time with the artist.

I have had so few interviews this year not to be two hours. Maybe, it’s because of COVID, and the lockdown. But I have had so few interviews under two hours this year that I am almost starting to not want to do interviews. They (artists) just go on and on and on now. Interesting stuff. Super interesting stuff. But if you are getting 2,500 words, what do you do with all of the other stuff? In my case, I use the best of it.

Why the title “Woman Walk the Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives” for your book?

Emmylou Harris has a song that I think is the fulcrum song of her 1985 album “The Ballad of Sally Rose” called “Woman Walk The Line.” It’s the moment when her mentor, the Singer, as he’s known, has died, and she is picking up the pieces of her life, and figuring out, “What the hell am I going to do?” One of the things in the song that becomes very clear is that she is taking on a real sense of her power. There’s an amazing lyric,

“Yes, I’m as good as what you’re thinking

But I don’t want hold your hand.”

(The Ballad of Sally Rose,” Emmylou Harris’ first entirely self-written album tells the story of a young woman who meets a famous singer and joins his band. They fall in love as she develops her own voice, then part when complications ensue, and he dies in a car accident before they can reconcile.)

The immediate draw of “Woman Walk the Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives” is the country artists featured. What gives the book its considerable depth are the extraordinary women — educators, music journalists, artists, failed artists that have moved on but stayed connected to music, and newspaper warriors—that you chose to tell their stories. In truth, I knew very few of these extraordinary women, and the quality of their writing takes your breath away.

Many of the contributors had life-changing moments with music, and they cite the lyrics that made these first country artists so significant to them. What’s further intriguing about the book is several contributors are still struggling with their relationships with their musical heroes.

Many of them are people struggling to conquer ties of who they are, and what they mean in the world now.

How did you talk University of Texas Press into doing the book? Didn’t you already have deal there for an Emmylou Harris book?

Yes, I had a contract to do an Emmylou Harris book. At the same time that I got that contract, I also got accepted to grad school, and David Menconi, my acquiring editor went back to the University of Texas Press for me. He said, “She can’t do both. She’s got a partial scholarship. She needs to do that.” They graciously allowed me to go to grad school to get my master’s at Spalding University in Louisville, Kentucky.

What I learned from that kind of intense workload, and that level of writing, is that there are so many amazing women writers that because of the internet that are going to disappear. Ronni Lundy was one of the really great female critics at the LouisvilleTimes and Louisville Courier-Journal (in the ‘80s and early ‘90s covering the likes of John Hartford, Emmylou Harris, Sam Bush, Dwight Yoakam, and Bill Monroe), and she barely exists today as a music writer.

Ronni went on to become a formidable author and editor with a focus on traditional American foods and music.

Still, many of these voices are from people which a general audience would not be familiar with.

That was very much by design. Ronni, in between the time that she turned in her essay (on the late iconic bluegrass singer/songwriter) Hazel Dickens, and the book came out, won the 2017 James Beard Foundation Book of the Year Award (for or excellence in culinary writing) for her cookbook “Victuals: An Appalachian Journey, with Recipes”).

Cynthia Sanz, who did Mary Chapin Carpenter, was named the executive editor of People (and then promoted to editorial director of news and human interest at People). Nancy Harrison, one of the founding producers of “Access Hollywood” (as supervising producer of music), who wrote about Dolly Parton, went on to become a really big deal at the Paley Center For Media (as senior booker), and now is supervising producer for People magazine.

Did you know these contributors beforehand?

I knew most of them going into it. Part of what lit such a fire under me was knowing that most of them would never be properly found. Google Holly Gleason at Rolling Stone and one article comes up, and I was in Rolling Stone every issue for close to four years. One article comes up. And it’s a shame because it’s the last thing I wrote for them. That was when I got jaundice and an editor changed some things in my copy that changed the entire tone of the piece.

Prior to the internet, magazines and newspapers had morgues where articles were retained. Those don’t exist anymore. From nearly five decades of writing about music, I can find only a handful of my articles online. As you were getting your masters you realized how many outstanding women, especially pre-internet, had written about music, and would most likely be forgotten because they hadn’t published books of their writings.

Yes, I existed pre-internet, when people still had morgues. So most of my work for just about everyone doesn’t exist. I didn’t want these women to also get lost. They were important voices in different ways and then some of them are women who may never decide to write a book. Elysa Gardner was the lead pop music critic at USA Today for 16 years. As well as their theatre critic. She’s incredible. But nobody understands what a great pop music critic that she is. She may never write a book. So she’s here, writing about Taylor Swift.

Alice Randall’s chapter on pianist, composer, arranger, and bandleader Lil Hardin was an eye-opener for me. I knew of Fleecie Moore, Louis Jordan’s wife who was given writing credit for “Caledonia,” as well as a co-credit for several other of Jordan’s most important songs during their marriage in a publishing scheme gone awry, but I had overlooked Lil Hardin who was a guiding light for her husband—Louis Armstrong.

(Lil Hardin successfully established a career as a respected jazz composer and artist. She played piano on Jimmie Rodgers’ quintessential recording of “Blue Yodel # 9.” Hardin wrote many hit songs for her Louis, including “Struttin’ With Some Barbeque,” a Dixieland standard. Ray Charles charted with her hit tune “Just for a Thrill” in 1960).

It was so interesting reading about how Lil Hardin inspired Alice Randall,

the novelist, songwriter, educator, and essayist, known for her work exploring African-American history and identity.

(A graduate of Harvard University, Alice Randall serves as a professor and writer-in-residence at Vanderbilt University. With more than 20 recorded songs to her credit, including co-writing with Steve Earle, sheis the first African-American woman to co-write a #1 country hit, “XXX’s and OOO’s (An American Girl),” recorded by Trisha Yearwood in 1994. Randall has written such novels as “Pushkin and the Queen of Spades,” “Rebel Yell,” “Ada’s Rules,” and the New York Times bestseller, “The Wind Done Gone,” an unauthorized parody of “Gone with the Wind,” told from the perspective of a mulatto slave.)

The Lil Hardin case is fascinating. One of the things that was incredibly important about this book is that women who love country music do not have role models on the radio anymore. Like Cindy Watts, who is not in the book, and who was the country music critic at The Tennessean. She told me the saddest story when the book came out in hardback. That her daughter had gone to do her school music talent show, and she picked a song from the (Disney Theatrical Productions) musical “Frozen” because there really weren’t girl singers on the radio that she was hearing, and what she did hear didn’t relate to her at all as a human being.

I called Alice to do Mickey Guyton because Alice had been a big advocate of Mickey’s and, however Alice’s life actualized, this would be a great story.

Mickey is a rare African-American voice in country music who had the hit “Black Like Me,” went to No. 4 on Billboard’s Digital Country Song Sales chart, and was later nominated for a Best Country Solo Performance Grammy, making Guyton the only Black woman ever to receive a nomination in that category.

(Black female artists making a serious run at mainstream country stardom. are rare in Nashville. In 2020, when Maren Morris, accepting the Country Music Association’s award for Female Vocalist of the Year, cited 6 Black women for their recent contributions to the genre, Mickey Guyton, Linda Martell, Yola, Rissi Palmer, Brittney Spencer, and Rhiannon Giddens. You can also add Miko Marks.)

What was Alice’s reaction to you asking for Mickey Guyton?

She said, “I totally know why you are asking for that. Then she laughed. She said, “When I was working on the Ken Burns’ “Country Music” series, and I was doing research, I found out about Lil Hardin.” And she told me the story, and she said, “That so completely mirrors my experience in the field.”

You sought out contributors that cover a diversity of sexual orientations, as well as gender, and sex identities.

I wanted to make sure that people that are Native American, people who were old, people who were young, people as you say were artists or wanted to be identified as a woman, I wanted everybody represented.

I have never thought of female country artists from that perspective other than with k.d. lang which is obvious, and Kelly McCartney did a superb job with her chapter.

That one, ironically, I thought was too obvious, but I really love Kelly and I love what she does.

Another highlight of the book is your chapter on Tanya Tucker. You didn’t start out as a fan. Tanya recorded one of your favorite songs, John Prine’s “Angel From Montgomery” which turned your head as did an alluring full-length cardboard retail standup of Tanya holding a fist full of dynamite spandex catsuit for the 1978 MCA “TNT” album.

I’m such a big fan of Tanya’s. but I never thought of her in terms of how she could be a role model for females. But, as women in the rebellious culture of ‘70s began to find their voice, so did Tanya, as she broke country music’s grip on tradition.

That standup was so full-frontal. I just remember walking around the record store, and everywhere I looked, there was this stand-up staring at me. I picked up the record, and I went ahead and bought it. I remember my super-cool grandmother saying, “Are you sure? What will your mother say?” My mother said, “She looks like a whore.”

Many male music critics thought that of Tanya as well.

It is always what I say about men rock critics in hearing female artists. There is so much that a female artist brings to what she’s doing other than people the object of the male gaze. In fact, I think that women writing as the object of the male gaze is a fair and recent conceit, and most of what goes on with women good and bad happens under the skin.

Having examples or role models is a big deal. Often it’s very apparent. To write about Loretta Lynn is to write about one of country music’s most ardent feminist voices. Her catalog of self-penned songs from yesteryear, dealing with marriage, the dynamics between men and women, changing sexual roles of women, and the ravages of alcoholism, remain as timely and as politically charged today.

In her essay about Loretta, writer Madison Vin wrote, “I chew on the possibility that if Loretta Lynn hadn’t spoken up, my mother might have been quieted, ignored—dulled. My mother is effervescent. no matter the room, her aura fills it. But what if she wasn’t allowed to be? Would my sisters and myself have then, in turn, been taught to bite our (admittedly sharp) tongues? Would we have been saddled with a universe of gray?”

It is harder, perhaps, to get a fix on Barbara Mandrell, known for a long series of country hits in the 1970s and 1980s, and her own primetime variety TV show “Barbara Mandrell and the Mandrell Sisters” on NBC that helped her become one of country’s most successful female vocalists of that period. Nevertheless, she recorded sex-tinged relationship songs like “Sleeping Single in a Double Bed,” “(If Loving You Is Wrong) I Don’t Want to Be Right”, and “It Should Have Been Love by Now” with Lee Greenwood.

In her chapter, Shelby Morrison, director of Artist and VIP Relations, at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, relates how she was tending bar in Lubbock, Texas, and took the rules she learned on “The Barbara Mandrell Show” and used them to get not only a job at the Buddy Holly Museum, but find the gumption to move to Cleveland, Ohio, at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

Can men relate to that kind of story?

I don’t say that men can’t appreciate them. One of the funny things somebody said to me (about the book),“This is the playbook from behind enemy lines.” If you want to know about women, about what they think, how they see the world, what their hearts are really made of, this book is the book.” And I thought, “Wow, really?”

You have Ronni Lundy learning what it means to be free and strong in the ’70s through Appalachian mountain musician and activist Hazel Dickens. Ronni, at 71, just won the top James Beard Award for “Victuals,” a book about Appalachian foodways.

I met Hazel Dickens at the Charlotte Douglas International Airport in Charlotte, North Carolina on the way to Folk Alliance to Memphis, and my heart skipped a beat because I grew up with the music of Hazel and Alice (Gerrard), the pioneering women in bluegrass, and their music grounded in the coal country traditions of Dickens’ West Virginia.

Their influence extended beyond bluegrass to commercial country music. Their arrangement of the Carter Family’s “Hello Stranger” became the blueprint for Emmylou Harris’s version of the song, and their adaption of “The Sweetest Gift (A Mother’s Smile)” inspired Naomi Judd, then a single mother in rural Kentucky, to start singing with her daughter Wynonna.

I was absolutely in awe of her.

Hazel reflected on her early days on the bluegrass circuit with Alice in a 1999 interview for the American roots music magazine No Depression. “I’m not sure if they looked at us as a novelty, or if they took us seriously,” she said of the male acts with whom they shared bills. But, she added, “There were a lot of them, especially down through the years, that gave us respect.”

Country music over the years has had its changes but as Emmylou Harris once said, “If it sounds country, it’s country.”

All music if it is living is morphing. If you stop morphing it’s time to get pressed between glass or frozen in amber and be dropped off at The Smithsonian Institution or the National Science Museum.

It’s six years after ‘Tomato-gate,’ an uproar sparked by radio consultant Keith Hill, who compared female country artists to tomatoes in a salad. “If you want to make ratings in country radio, take females out,” he said in 2015. “I play great female records … they’re just not the lettuce in our salad. The lettuce is Luke Bryan and Blake Shelton, Keith Urban, and artists like that. The tomatoes of our salad are the females.”

In 2013, there was a report on the dismal numbers of women on the Country Airplay chart — and mention of the unwritten rule that two women’s songs could not be played back-to-back on the radio.

And there are reportedly even fewer female voices today on country radio.

Well, the trouble with stats is that you can dance them all kinds of different ways. You can have a record that can take a year to go to the teens (of the charts), a year of someone’s life, and it starts hitting. I remember what just getting a nomination for Female Vocalist for the Country Music Association was like. Damn, there was a time when all of these women were on the charts. Trisha Yearwood, Patty Loveless, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Martina McBride, Kathy Mattea, Suzy Boggus, Shania Twain, Faith Hill, Wynonna Judd, Sarah Evans a little bit behind them, Pam Tillis, Tanya Tucker, Chely Wright. She didn’t last very long, but she was in that mix.

Michelle Wright from Canada was a contender for a moment.

She’s another one. She had a minute. There was a minute for Chely Wright’s “Single White Female,” and Michelle Wright’s “Take It Like A Man.” They were fairly enduring singles.

Those are two acts of the many country acts that should have broken through.

Well, let’s not do that. I know more about why a lot of these people don’t happen.

Well, bad career decisions, perhaps, lack of direction, and so on.

That’s their unique story, right? I know all of what went on on other the other side too. In a lot of cases I watched it. Some of it is that you get the career that you deserve. Some of that is how you treat people. Some of it is who are your advocates. Like, I see publishers today who, based on the work that they do, I could never write about their artists. The signing photo looks exactly like every other signing photo that has come out of Nashville. You kind of go, “If this is how you think you engage people…”

Well, you worked as a publicist for CBS Nashville so you know what is required.

No no no, beyond that I was working for HITS. I am a journalist who grew up in this business. I did homework on Neil Young’s bus. People acted like i was young and dumb, not watching and paying attention to what works, and what might be destructive or undermining.

You’ve written songs under the name Lady Goodman and contributed the chapter on Lucinda Williams in your book under that moniker.

As a songwriter, you and Travis Hill (as Scooter Carusoe) co-wrote “Better As A Memory” a #1 hit in 2008 on the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart for Kenny Chesney, and it reached #46 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. and produced by Buddy Cannon, the tune was also voted one of The Nashville Songwriters Association International’s “Ten Songs I Wish I’d Written.”

You also co-wrote with Guy Clark (“Just To Watch Maria Dance”), Rodney Crowell (“The Train Is Leaving The Station”), Charlie Pickett (“What I Like About Miami”), and Jim Lauderdale (“Almost More Than All The Joy.”)

And you’ve co-written with Bill Deasy, Matchbox 20’s Kyle Cook, Restless Heart’s Larry Stewart, Marc Lee Shannon, Andrea Zon, and extensively with Matraca Berg.

After co-writing “Better As A Memory” and having #1 hit, why didn’t you become a full-time songwriter?

First of all, nobody knew it was me until over a year later when the song went to #1. Kenny knew. Kenny was in on the secret.

Kenny didn’t know when he accepted the song?

He had no idea. He knew that it was a Travis Hill song. He knew that. He got the song, and he was kicking off a tour. I had a friend who said, “You have to give it to him.” Travis burned a CD while I was picking up my laminate to go out and meet the tour. It was a guitar/vocal that was recorded while I was going to get a laminate. I got the laminate, I swung by Carnival (Music), got the CD. We didn’t have a lyric sheet, and I left the CD on Kenny’s pillow, and I said, “Hey, this is a lullaby. I know how hard you are rocking and where your adrenaline must be. Welcome to another summer.” Then I got picked up the next morning at the airport by my ex-fiancé John Hobbs, the piano player.

And he said, “I thought you said that Kenny’s album is done.” I said, “Yeah we’re working on writing parts of the bio.” He said, “Well, we’ve been called for a session for Tuesday.” I said, “That makes no sense.” Then I got a call about 90 minutes later from Travis saying, “What the hell is going on? They just called for a lyric sheet.” The irony was that Travis was so freaked out, “The first line of the song is wrong.” Then he wouldn’t let me tell Kenny to correct it

The lyric recorded is “I move on like a sinners prayer.”

It should be, “I hold on like a sinner’s prayer.” Not move on. Sinners’ prayers don’t move on. It’s the last thing they have to hang on to.

As a wordsmith, a wrong lyric must have driven you crazy.

Oh, the debate about, “I don’t want to be that mistake” versus “Don’t you make that mistake” that was at least 90 minutes. It’s not that it drives me crazy. It’s wrong. So then at 2 o’clock Kenny called me with a hangover going, “How did you get this song away from Travis? I was like, “Well, he plays me stuff, and it just felt like you.”

I was there when they cut it. My ex-fiancé played on the track. He was my ex-fiancé at the time, but people were so used to seeing us together because we are buddies. Just because we didn’t get married doesn’t mean we don’t love each other. And Hobbs said, “Are you going to tell him?” And I said “No.” and the more I thought about it, the more I thought he was going to be angry if he didn’t know.

So as we were finishing up his bio interview, I said, “I have to tell you something about the song.” He was like, “What?” I said had been setting it up for Ronnie Dunn. But I think he saw it on my face, and he goes “Did you write that song? Are you the co-writer?” I said, “Yeah.” Kenny knuckle bumped me across the table, and said, “God, if I had written that song I would be taking out billboards on sides of buses.”

I said, “Well, here’s the deal. You can’t tell anyone. I don’t want to be a distraction. If anybody knows or suspects it will turn into another narrative and the truth is you cut the song because you loved the song. You didn’t cut the song to throw me a bone.” He said, “No I didn’t cut it to throw you a bone.”

What a thrill having a #1 hit record.

Was it a thrill? Oh, my God. I was leaving a screening of the Rolling Stones movie “Shine a Light” at the Regal Opry Mills Imax theatre the first time I heard it on the radio. I had to pull over, and I just sat there and cried. And cars were going by me because the screening had ended.

Guy Clark was such a meticulous tunesmith. It’s one thing to be friends with someone like Guy but to get him to write with you is another thing. “Just To Watch Maria Dance,” was featured as a demo on the retrospective collection, “Guy Clark: Best Of The Dualtone Years.” How did that co-write come about?

I used to call him Uncle Guy. He used to break up my relations with boys for me. He took pleasure in that. He took such joy in – literally – doing that awkward part of telling guys it was done. His signature move usually went something like, “Let me tell you how this is going to work: she’s going to walk you out, then she’s coming back here – and we’re going to talk about you. But, hey, you had a good run.”

Still a big step to ask him to write with you.

I knew if I asked him directly, he couldn’t say no, but I didn’t want him to be trapped. So I went to somebody at the publishing company, and I said, “Would you call Guy. Start with the answer is ‘no,” and ask if he would be interested. I had a lyric that I had started in a truck stop 51 miles out of Cleveland, “Greyhounds are for leaving, when all you got is gone.” I got a call back. And he had said, “Tell Holly she needs to call me and we’ll set this up ourselves. We’re done playing official. We can just play like we are songwriters.” That’s what I did. I called him, and Guy said, “Well this is the first good idea you’ve called me with this year” I’m sure he was teasing. “I’ve got my book out.” Boom, boom, boom. “One of these dates work for you?”

I was afraid to give him my idea. I had another idea I wanted to write. It was something that had happened to both of us. That sounded a lot more delicious than it was but it was one of those things. He said, “I’m not going to write that with you.” I was, “Okay.” So we tried to write a song and it was terrible. I will tell you. The reason why Guy is so respected is because he’d chase a bad ideas down because there may be something good in it. Then I came back the next day and I said, “Please let’s destroy this. I don’t want anybody to think you would have a part in anything this terrible.” He said, “If you want to kill this song you’ve got to give me an idea.” So I said, “I’ve got this lyric and that’s why I called originally. He looked at what I had and he said, “This is really good Holly.” And so we started there.

What did you learn from being a publicist that you could bring back to your journalism?

As a publicist, I learned that writers are only as good as what you give them. If I give you sloppy materials or I do, “Today we will release this record,” then you don’t have anything to work with, to dream on, to spring off of. And I think that I learned that it is important not to just chase basic facts but also to challenge artists too. I think that too many people, and this is across the board. and this is not a criticism of publications—but they are so busy being afraid of offending the artist that they don’t push some to be great. You have to be brave enough to risk the artist biting you, maybe, on the face.

I’m also a top journalist. I’m not somebody who has been in a music business program who has heard somebody who might have a notion.

You had a 35-year friendship with John Prine, his family, and his surviving longtime manager Dan Einstein, and you often traveled with him on tours in the late 1980s and represented him in the 2000s. Upcoming on April 12, 2022, from Chicago Review Press as part of its Artists in Their Own Words series will be “Prine on Prine: Interviews and Encounters With John Prine,”which you have edited.

When I was little, I heard Bonnie Raitt’s version of “Angel From Montgomery” and I realized that the spaceship was not coming back to take me home. I was not the Little Prince. This is not Antoine de Saint-Exupery (author of “The Little Prince.) That song was life-changing because it said, “You are here, and get on with it.” And I did and I started getting into his songs. He’s unbelievable.

The lyric line that resonates more than anything else is, “How the hell can a person go to work in the morning / Then come home in the evening / And have nothing to say?” There’s a lot in that song but that’s the line that hangs you.

Well, there are a lot of lines that hang you in that song. For me as a little kid listening to WMMS, where I don’t understand a lot of the music, where there are lines that there about people shipwrecked in houses that are so disengaged, it floored me.

So fast forward. I’m a senior in college in Miami, and I interview John. He came to play a movie theatre in Palm Beach. The Miami Herald editor Doug Adrianson I mentioned earlier told me I should take the job at the Palm Beach Post. He said, “I don’t know when we are going to have a staff job, and I think you are very good at writing about music. You should take this job.”

So I did, and then the Herald happened not to run my interview. So I called Dan Einstein at Oh Boy Records and told him what happened. It’s a week before I am starting at the Palm Beach Post, and Post gave me $100 for this review to kind of make it right.

At the show, John steps over the monitor, singing “Lulu Walls,” and he starts laughing, and he says, “Hey Holly, glad you could make it.” And he steps back over the monitor, and forgets the second verse of “Lulu Walls,” because he was so delighted that he made me jump out of my seat. After the show, I went up to him and I said, “Look I’m really sorry. I took this other job. I’m going to review the show.” He said, “It’s alright.” We had this nice talk, and he sort of became an uncle. He really took an interest in me. He told me, “You are really smart and I don’t do many interviews because I don’t like talking to people, but you are really great. They warned me that you were really young, and you didn’t talk to me like a kid” I was like, “Oh my God, would you be my best friend?” John, in part, was cupid, I ended up with my third fiancé Dan Einstein who was his co-manager, who built Oh Boy Records, and Red Pajamas Records. John engineered that. As I went through life, John was always right there at my elbow. I traveled with him a lot.

You grew up in Shaker Heights, an inner-ring streetcar suburb of Cleveland?

Yes, the poor part, and there is a poor part of Shaker Heights.

You grew up on the Cleveland music scene, and the powerhouse radio station WMMS-FM with music director Kid Leo who boosted the careers of Bruce Springsteen, Rush, Mott the Hoople, John Mellencamp, Pat Benatar, Roxy Music, Cyndi Lauper, the Pretenders, New York Dolls, and Southside Johnny. Kid Leo went on to a great career at Columbia Records, where he was involved with campaigns that broke Alice In Chains, Shawn Colvin, and Train.

Kid Leo was the afternoon DJ at WMMS-FM. I was a kid, and my relationship with WMMS was in the backroom of (golf) pro shops, smelling gasoline that was being used to strip grips off golf clubs. And there would always be one of those big transistor radios propped up in the window that was open to let the fumes out.

Cleveland, the self-anointed rock and roll capital of the world.

I think of Cleveland now in that (Tanya Tucker) essay in the book, and it’s is about how our self esteem came from how much we loved music. You went to a show in Cleveland, and when I moved to Florida toward the end of high school, and when I was living in California, and when I was on the road, I never saw audiences like the audiences in Cleveland. It was a little disorienting to me in Miami.

You went to shows at the Agora Ballroom on East 24th Street near the campus of Cleveland State University?

Yes. I snuck into the Agora. I would wrap my library card up in the appropriate amount of money. I would also go to shows at Peabody’s, Room One at John Carroll University, the Greenville Inn, Rick’s Cafe in Chagrin Falls, as well as the Coventry Street Fair, and the Hessler Street Fair. I was going to the Blossom Music Center, a little bit to Municipal Hall, Peabody’s which became Peabody’s DownUnder in 1984. which had been Pirate’s Cove. I didn’t go to Pirate’s Cove, that was a little too scary. Also, in the early/mid-80s, when I was truly running around with musicians, I’d go to the Euclid Tavern (known as “E.T,” not the “Uke” as the 1987 Joan Jett/Michael J. Fox movie “Light of Day” called it.

As I got to know the local bands I had a lot of “uncles.” Everybody knew that the band would stand up for me because I didn’t drink and I wasn’t obviously looking to pick up guys because I was too little. So the musicians had a kid who just loved them, and the music and what would you like to know? I heard “The Tattler,” that Deadly Earnest the Honky Tonk Heroes played, and I thought, “What is that? Who wrote that? Who is this guy? Where did it come from? Tell me everything.” Then they would tell me all about Ry Cooder and his (1974) album “Paradise and Lunch.” So I was really blessed because those people, those musicians, knew me. I could ask them anything; they were so generous with what they knew.

So I was really blessed because those people knew me. So that was the other thing. I couldn’t drink in the bars. It was like, “There’s the kid that plays golf.”

Cleveland in the ‘70s and ‘80s was rock.

There were some great Cleveland acts then including the Michael Stanley Band, Alex Bevan, Pere Ubu. Wild Horses, the Janglers, and the Buckeye Biscuit Band.

You have written that you saw Alex Bevan sell 50,000 copies of his 1976 album “Springboard” out of the trunk of his car; and that Michael Stanley sold out Blossom Music Center five nights in a row.

Alex Bevan isn’t as well known as Michael Stanley who died in March. There’s now a 2,200 square foot mural, painted by well-known Los Angeles street artist “WRDSMTH on Cleveland’s Payne Avenue features lyrics from Michael’s 1980 song, “Lover.”

How do you know Alex Bevan? That’s fascinating.

Well, I live in Toronto which isn’t that far from Cleveland, and I was on the road as a publicist with Canadian bands that played there. Among my music industry rabbis was the late Steve Popovich, founder, and president of Cleveland International Records.

He’s a good rabbi. If Pops believed in you, you didn’t need anything else.

I remember Alex Bevan’s boogie hit, “Skinny Little Boy,” from his “Springboard” album. Such a great funky bar song.

“Skinny” was the rallying cry of every kid from Cleveland who didn’t get any respect. It was just about every one of them.

Alex Bevan was your first idol. You met Alex at 13 and you handed him a sheaf of papers, your poetry and lyrics. Years later, you worked with him on his albums, “Fly Away.” (2010) and “I Have No Wings” (2012) He credits you for helping him refocus his writing. You did some song doctoring for him.

Yes, Alex Bevan was my first idol. I went to see him at John Carroll University with one of the backroom guys. His mom was the accountant at Audio Recording where he made “Springboard” and I remember sitting there listening. He’s a beautiful finger picker. I came to find out later that he was Odetta’s favorite opening act. Steve Goodman, and (bluegrass icon) Jethro Burns used to throw him into the back of their Lincoln, and drive him around when they toured in the Midwest. I guess he would go out and do runs with them. He’s really is a beautiful finger picker. There was something about the gentleness and the beauty of the way that he captured emotions. He didn’t tell me how he felt. He didn’t show me exactly, but somehow inside my body, I understood. And I was so intrigued by the magic of how he did it that the first time I saw him. I started writing some poetry, and I would wear the same clothes every time that I saw him so he would remember me. He was always super gracious. He never treated me like a little kid. He subsequently said to me, “You always asked smart questions. I don’t think that I realized how young you were. You looked young, but I don’t think I understood how young you were. And you weren’t a bad poet.”

Did you write songs with Alex?

I did some song doctoring for him, much, much later. I would never say that I wrote with him.

You were never intimidated by the music personalities that you met?

The reason that I’m not afraid of famous people is because I went through the eye of the needle in walking up to this person whose songs meant so much to me. And he was respectful. He talked to me like an equal.

You were awfully young.

For context, I was a little kid. We are talking 13, 14, and 15. I was going to concerts at that age. I was a championship golfer who was on the road and playing tournaments. It wasn’t a business, junior tours, when I was on the road. Now kids can be on the road all of the time. If I wasn’t gone playing in a golf tournament, I was playing in a golf tournament in Cleveland. I played in a lot of tournaments, but I never played in title flights. I was only in the second or third flight. But when you are a kid you stand out.

Did your early golf success help prepare you for a high-lever media career?

Oh, my golf success wasn’t what you think. My golf success looked so much better on paper than it did in reality. My father understood how to get my picture in the paper. And I understood how to give interviews to local TV stations.

Do you still play golf?

Just a little. I got hurt. That is why I got into writing about music. I got hurt, and I met the lead singer of Pure Prairie League, Vince Gill, who needed a golf buddy. He had a week off between grad night appearances. We played golf for a week, and I interviewed him. I spent so much time playing golf with him that I hadn’t turned in my journalism final and I had to turn in something for the last issue of the school paper, the Saint Andrews Bagpiper. I’d kidnapped him, and interviewed him for my high school paper in Florida. He told me, “You should write about music”

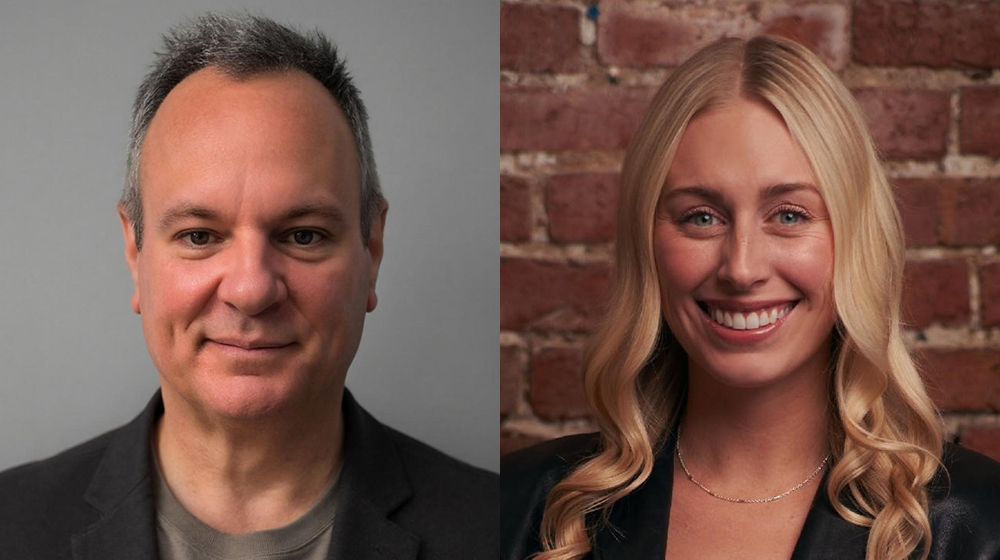

Larry LeBlanc is widely recognized as one of the leading music industry journalists in the world. Before joining CelebrityAccess in 2008 as senior editor, he was the Canadian bureau chief of Billboard from 1991-2007 and Canadian editor of Record World from 1970-80. He was also a co-founder of the late Canadian music trade, The Record.

He has been quoted on music industry issues in hundreds of publications including Time, Forbes, and the London Times. He is a co-author of the book “Music From Far And Wide,” and a Lifetime Member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

He is the recipient of the 2013 Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award, recognizing individuals who have made an impact on the Canadian music industry.