(Hypebot) – By Jason Epstein and Rob Glaser, members of the board of directors of Rhapsody.

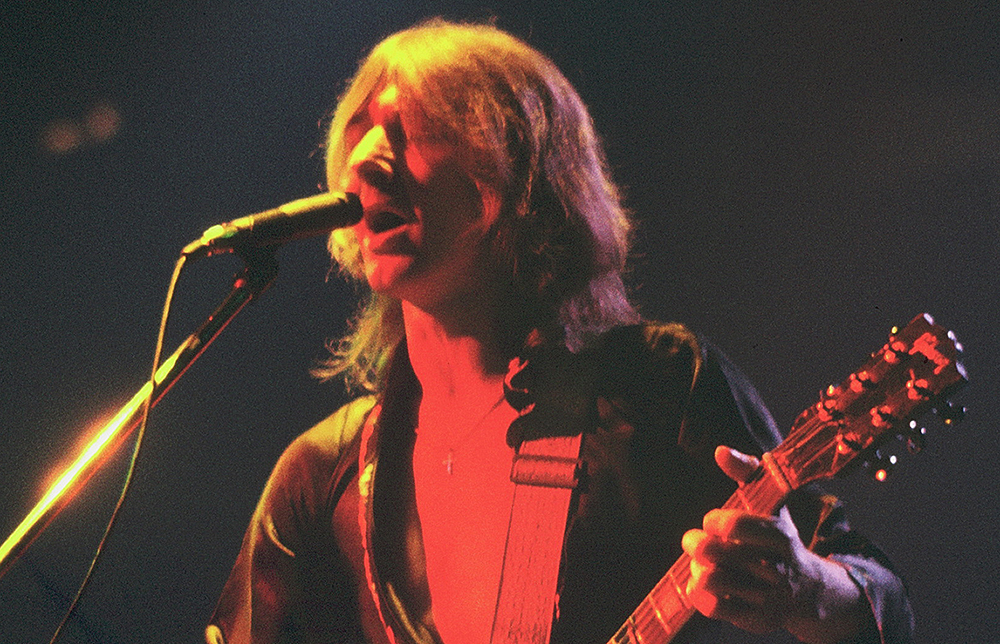

“There’s somethin’ happening here, what it is ain’t exactly clear … ” — Stephen Stills

When the legendary American rock band Buffalo Springfield sang those words in 1966, they were singing about a youth uprising in LA, at a place called “Pandora’s Box.” Little did anyone know that almost 50 years later these words would be an equally apt way to describe another youth uprising, surrounding another Pandora, as well as a Spotify, a Rhapsody, a YouTube and an iTunes.

Today, the music industry is at a crossroads. The Faustian deal that the music industry made with the late Steve Jobs — make every music track available for $1 on iTunes — isn’t working. Physical record sales continue to decline, as they have every year for nearly a decade. But now digital track sales are declining, too — iTunes music sales are down by more than 10 percent this year — and the recorded music industry is scrambling for a solution.

The hot question of the moment is whether streaming on-demand music services are the answer to arrest the recorded music industry’s decline, or whether the industry is about to enter another protracted downward spiral. The flash point for this has been Taylor Swift’s decision last week to remove all of her music from the free streaming service Spotify. Other artists have followed suit in recent days with their latest albums, including Jason Aldean, Justin Moore and Brantley Gilbert.

As a pioneer in streaming music — in 2002, Rhapsody was the first music service to offer streaming music from all the major labels — we are big believers in streaming as a key part of the answer for both consumers and the recorded music industry. Indeed, earlier this year we crossed two million paid subscribers, making us the No. 2 on-demand music service in the U.S., and one of the top two in many countries around the world.

So it may surprise you that we support, and generally agree with, the decision by Swift and these other artists to not have their new albums available on free streaming services on the day of launch. Our reason? It’s simple. We think that insisting that every piece of content that’s in a premium tier also be in a free tier, as Spotify has apparently done, is overly simplistic and won’t break the spiral of a music industry in decline. Instead, we believe in a much more comprehensive approach that (a) differentiates between free services like Spotify and paid services like Rhapsody, and (b) is built on concepts like windowing and other innovative ways to deliver value to both consumers and artists.

Before Taylor Swift’s decision to pull her catalog from Spotify, most people didn’t understand the difference between free music-streaming services and paid ones.

Before Swift’s decision to pull her catalog from Spotify, most people didn’t understand the difference between free streaming services and paid ones. There is actually a big difference. On Rhapsody, everyone who has full access to the more than 30 million songs in our catalog is paying us, either directly or indirectly (for instance, through their mobile phone service plan). Whereas on services like Spotify, the vast majority of users aren’t paying anything — access to on-demand music is free.

Spotify’s model sends a negative message to consumers about the value of music. It also has very real practical implications. We pay the music industry approximately $65 per year for each subscriber. By contrast, based on their own published data, Spotify pays around $20 per year for each of their active users.

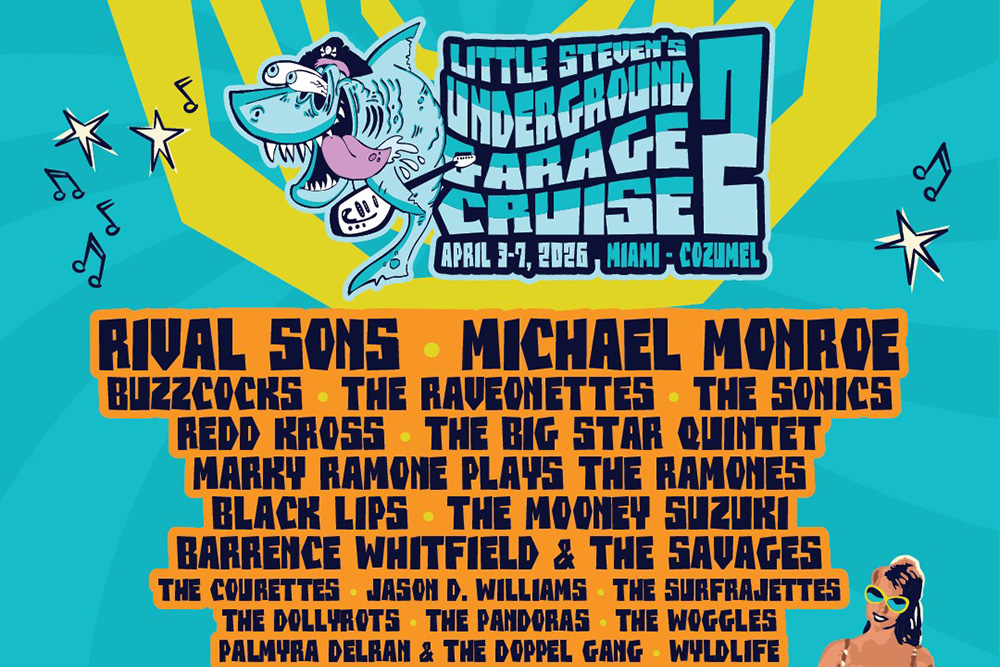

There’s certainly a role for free ad-supported services — radio has been around for over 75 years, and the popularity of Pandora clearly demonstrates how robust this model is. But we have long thought that the industry going all the way to free on-demand music is throwing the baby out with the bathwater. It’s heartening to see the industry figure this out and take action.

Windowing is clearly one way to differentiate free versus paid access. The fact that Swift is the first artist this year to sell more than one million copies of a new album — which she did in just one week — demonstrates that the model can work.

We already know that consumers are fine with windowing in other parts of the media world. The most common example of windowing is movies, which almost always open in movie theaters before moving to home video and television. Television also has this model — hit shows premiere on the network that owns or underwrites them, then they move to other distribution places later. Based on how durable box office revenues are, and how much consumers love shows like “Game of Thrones” and “House of Cards,” it is clear that consumers are perfectly willing to embrace windowing.

The key to making consumers happy is consistency and exchanging value for value. If 90 percent of new releases from established artists were only available at launch on paid services — whether by purchase, or as part of premium subscription services, such as Rhapsody, or through some new model — then consumers would quickly come to understand that premium services are the way to get access to all the latest music.

The result would be a win-win for everyone — more artists would get paid reasonable rates for their music, aggregate industry revenues would rise and consumers would get excellent, virus-free experiences, and would know what they were paying for.

Windowing is but one of a number of ways that the music industry can embrace the innovative possibilities that digital distribution offers. Rhapsody unRadio, which we launched earlier this year, is an example of innovation that we’ve recently brought to market. There’s more to come, and we are excited about what we have in our product pipeline for 2015.

We truly believe that streaming done right can be part of a future where recorded music is again a vibrant and growing industry. We look forward to continuing to work with the music industry to deliver compelling services that both consumers and artists will embrace and that keep the music industry vibrant and vital.